A. Introduction

As one aspect of its Fall 2011 Consultations, the LCO distributed a questionnaire to individual older adults. The questionnaire was designed to complement the other aspects of the consultation, including the focus groups and the Stakeholder Event, by gathering input from older adults across the province about their experiences with and perceptions of the law. Questionnaires were distributed to older adult networks throughout Ontario, including through the public libraries system and partnering organizations such as the Retired Teachers of Ontario, the Ontario Association of Residents’ Councils, Women’s Institutes, and others. The results were instrumental in developing the LCO’s Framework for the Law as it Affects Older Adults, and are reflected throughout the Final Report. This Appendix provides a brief overview of the results of the questionnaire.

It is important to note that this questionnaire was intended as a method of public consultation, and not as a validated social science instrument. Further, it was intended as only one aspect of the LCO’s consultations, which also included strategies to reach out to organizations and experts, and focus groups targeted to several marginalized groups of older adults. The questionnaire provided an opportunity for input to individual older adults not targeted by the focus groups. As all but one of the focus groups took place in Toronto, outreach to rural Ontarians through the questionnaire was important. As well, realizing that the questionnaire would be unlikely to elicit many responses from some groups, such as racialized, LGBTQ and low-income older adults, the focus groups were targeted to gather perspectives from such groups. Due to a very positive response and support from the long-term care sector, the questionnaire was also an effective means of providing an opportunity to contribute for this group.

A copy of the distributed questionnaire is appended to this document. It included a mix of scored questions and open-ended queries, focussing on three areas: principles to guide laws, programs and policies; understanding the circumstances of older adults; and enforcing rights.

B. Who Participated?

In total, 292 questionnaires were completed and returned to the LCO. Some reflected the responses of multiple individuals. The following is a demographic break-down of the respondents.

Age

| Under 45 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75-84 | 85 and over |

| — | 2% | 18% | 29% | 26% | 25% |

Gender: Female: 57% Male: 48%

Disability: Disability: 53% No Disability: 47%

Racialized: Yes: 4% No: 96%

Aboriginal identity: No respondents identified themselves as Aboriginal.

Sexual Identity

| Heterosexual | Lesbian | Gay | Bisexual | Tran-sexual |

| 98% | 2% | — | — | — |

Living With

| On my own | With a spouse or partner | With my children | With extended family | In a group setting |

| 13% | 27% | 3% | 1% | 58% |

Urban/Rural Residence: It was difficult to determine with accuracy the percentage of respondents living in urban or rural area. However, a review of the addresses provided by respondents indicated a broad distribution across the province.

In Canada for less than 10 years? Yes : 1% No: 99%

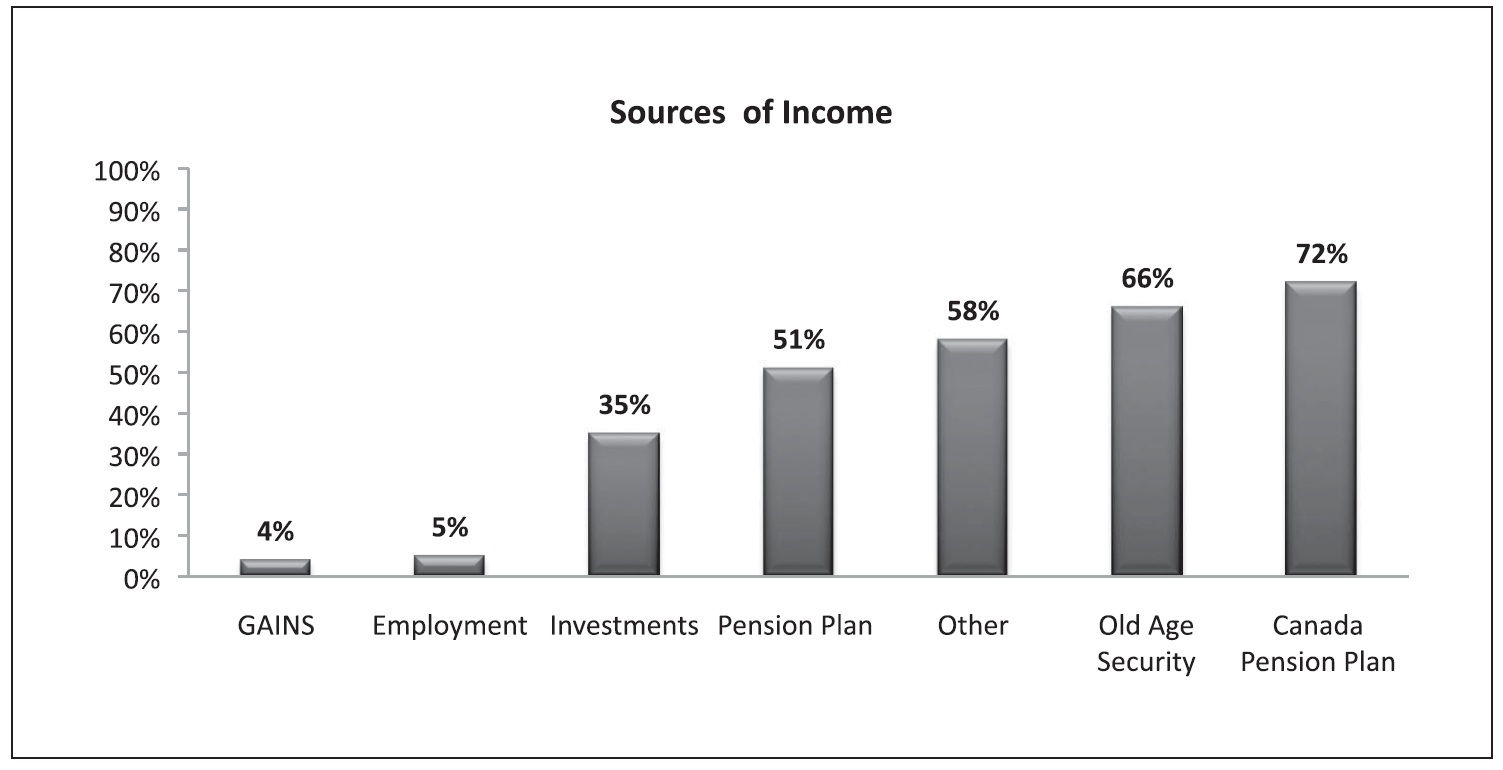

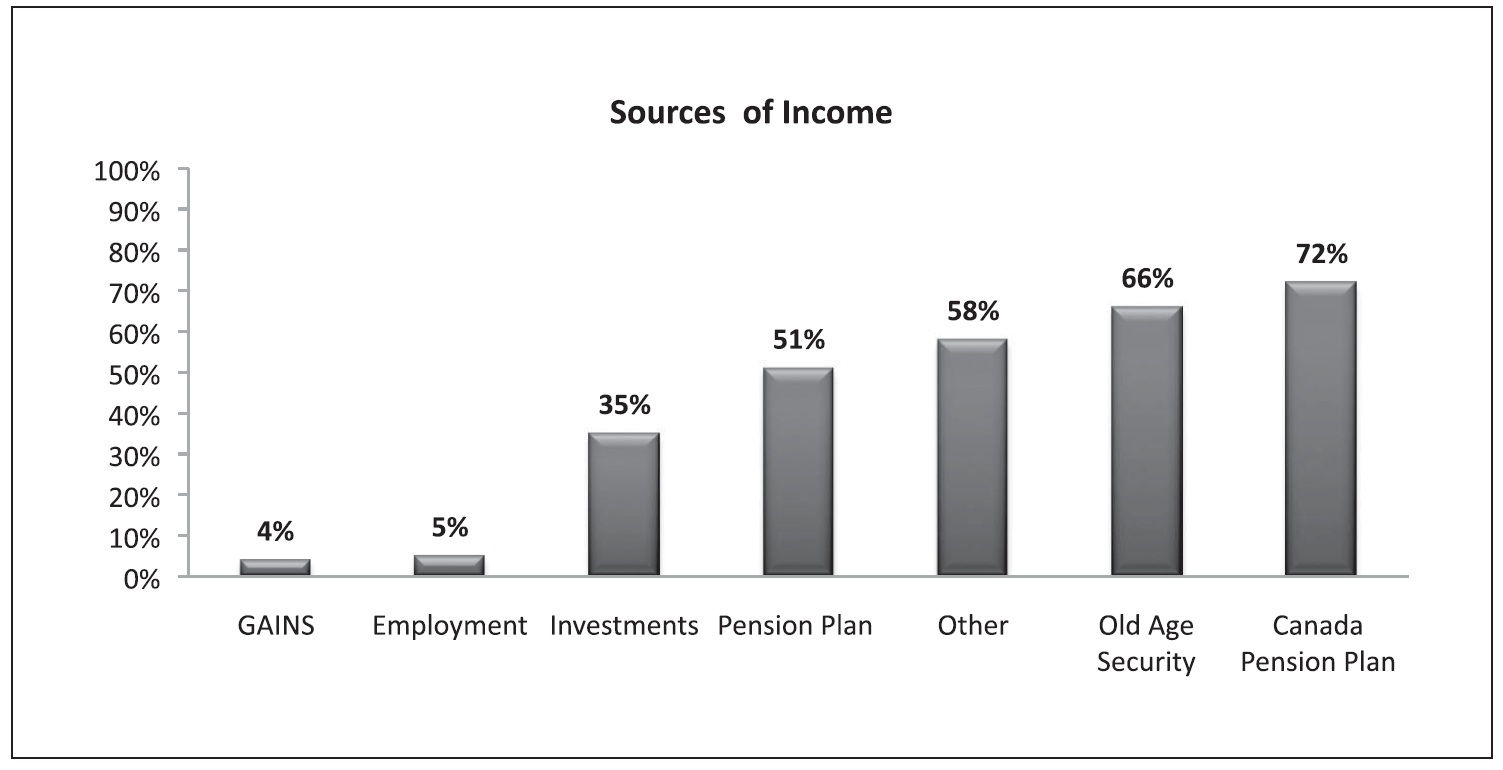

Of those participants who checked-off “other”, those sources of income came primarily from disability benefits, foreign country pensions, and financial assistance from family members.

Note: The results of the questions regarding race and sexual orientation should be interpreted with caution as many respondents did not answer the question, and some indicated an objection to the question.

C. Responses to the Questionnaire

1. Attitudes and Aging

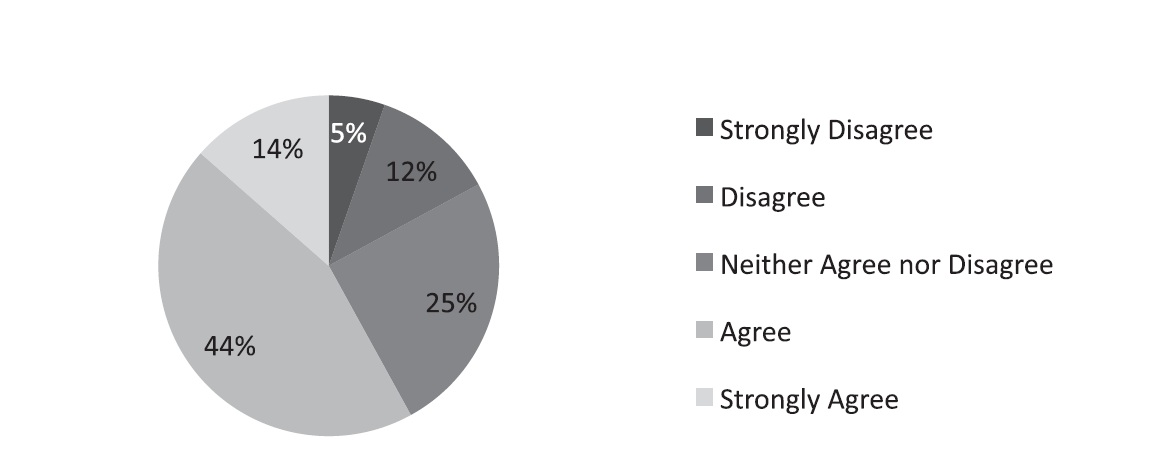

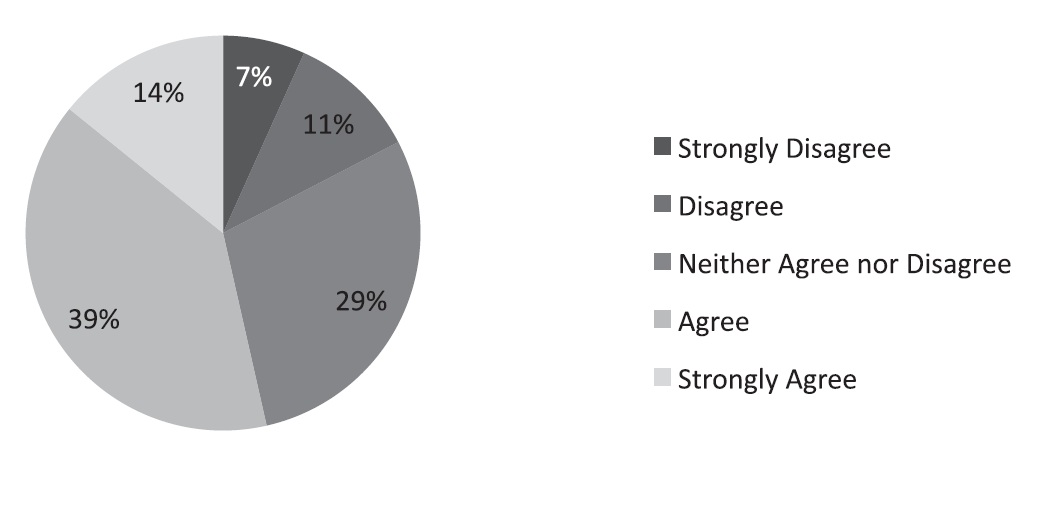

My older age is viewed as a positive attribute by people that I encounter.

Of those participants who agreed with the above statement (58%), many gave reasons related to the experience and wisdom they have accumulated in their general lives, their professions, and their volunteer work. Many claimed that “older adults…are experts in their field” and that younger generations appreciate this “expertise”.

Of those participants who disagreed with the above statement (17%), the primary reasons related to experiences of discrimination, devaluation or disrespect based on age. The instances of discrimination adduced ranged from the requirement of more frequent drivers licence testing to employment discrimination, which was a frequent complaint. Many respondents complained of being laid off or denied employment due to their age. Respondents experienced such instances of devaluation as being overlooked or being belittled, usually during social interactions. For instance, one participant made the typical complaint that “I am overlooked, when there isn’t anything wrong with my brain.” Another noted, “I find it problematic when I see…people automatically addressing the younger person accompanying an older person.” Comments regarding disrespect emphasized the media’s portrayal of older adults as “silly, foolish people” rather than people of dignity and intellect. Others noted the over-emphasis on older adult’s social and medical needs, while “the independence and self sufficiency evinced in most of our lives is overlooked”. Many participants also commented on patronizing treatment, assumptions of incompetence, and being talked to “like I’m a four year old”.

Respondents emphasized the importance of using public education to address negative attitudes related to aging. “Recognize the discrimination in ageism. The courts and society have recognized racism, sexism, homophobia, and disability but not ageism” remarked one man. Participants often reflected negatively on common stereotypes of older adults as incompetent, useless or frail, as well as stereotypes that depict older adults as a needy cohort, sucking up resources and requiring constant attention and care. Some respondents complained that even their own children and loved ones applied such stereotypes to them. They vehemently disavowed these stereotypes, and insisted that media and legislators promote anti-ageism education – both for the general public, and particularly for professionals providing services to older adults.

As an older person, I am usually treated as well as others when using public or private programs or services.

Positive comments about the above question emphasized the sensitivity and kindness of the public and service-workers toward older adults. Instances included the offering of seats on public transit, the giving of special assistance, the opening and holding of doors, and even the provision of “a little extra service” at banks and restaurants to older persons. Some participants also touted seniors’ discounts.

Negative comments about the above question focused on the perception that, as one ages, one receives less respect from store clerks, bank tellers and other service providers. Some respondents complained conversely that they had received patronizingly excessive assistance and special attention, leaving the older adult feeling demeaned and useless.

The public and private services and programs I use help me to achieve my goals as an older adult.

While the majority of respondents (68%) agreed with the above statement, their comments primarily centred on the lack of accessibility for people with mobility disabilities, both in public and private buildings and on public transport; lack of sufficient inclusion in the electoral process; and unclear or inaccessible information about services and programs.

Respondents particularly emphasized the difficulty of accessing services and programs, especially medical, commercial and financial programs, due to insufficient information (for example, doctor and nurse schedules), prohibitively complex information, or the incorrect assumption by those responsible for providing information that information commonly placed on the internet can be accessed by older adults. Many respondents complained of the arduous task of navigating automated telephone services to gain information, or of attempting to converse with workers who lack clear communication skills. One respondent, summing up the general sentiment, described the process of trying to obtain information as “a long and torturous procedure and not for the faint of heart”.

2. Principles to Guide Laws, Programs and Policies

Participants were asked to rate the importance of the following six principles as very important, somewhat important, not very important or not at all important:

-

Respecting the dignity and worth of older persons;

-

Promoting autonomy and independence of older persons;

-

Enhancing participation and inclusion of older persons;

-

Recognizing the importance of security for older persons;

-

Recognizing the diversity and individuality of older persons; and

-

Understanding that older adults are members of the broader community.

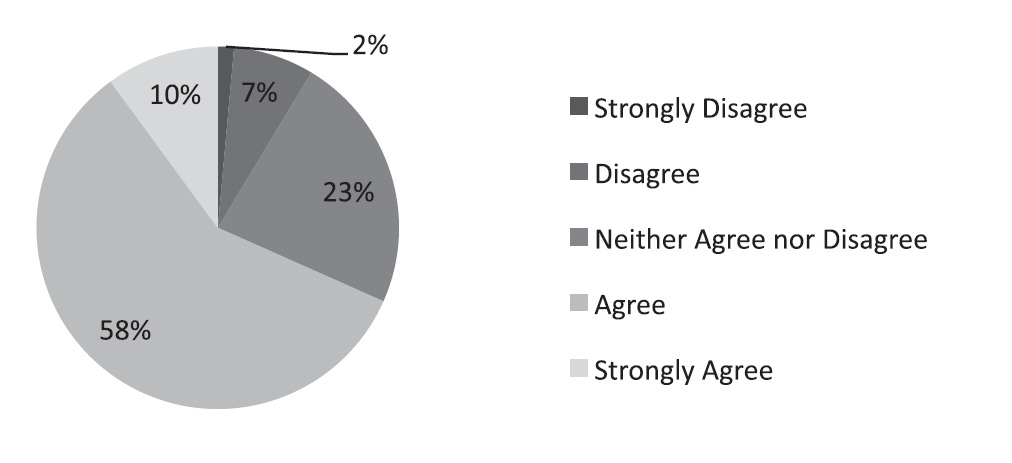

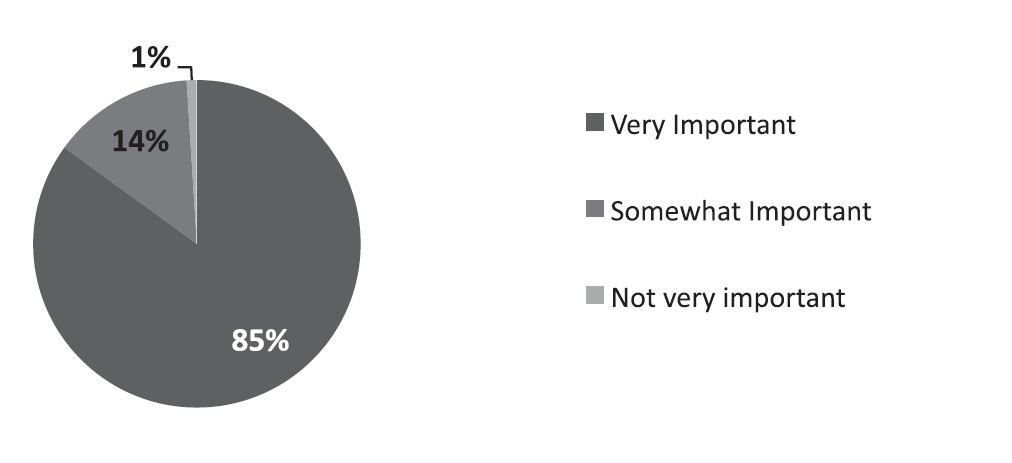

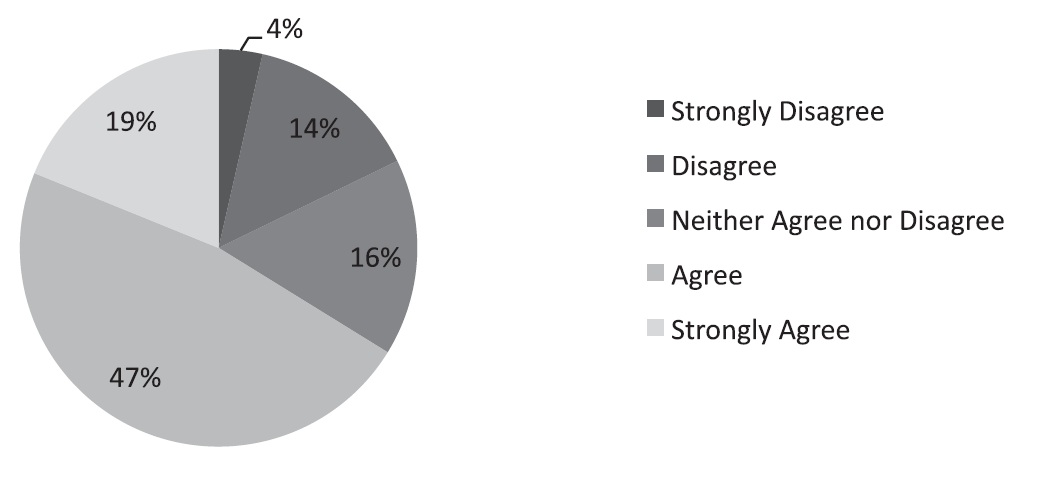

The answers for each of the six principles were very similar and, as such, the results have been averaged in the graph below to illustrate the general trend (note: no participants indicated that any of the principles were “not at all important”):

Responses explaining why the above principles were ranked in this manner focused on two primary rationales. The first was that older adults are no different than other individuals, and as such, deserve to be treated in the same way as other members of society. Respondents also discussed the idea that older adults have contributed to society throughout their lives, and continue to do so in many ways, and should therefore be respected and included in a similar manner to younger generations. Additionally, respondents emphasized that, like any other group of people, older adults are diverse, and should not be “lumped into one category.” In fact one respondent noted that, “instead of getting more alike, as we age we continue to get very different”.

The second rationale was that the principles are important because consideration should be made for the particular needs and circumstances of older adults. These include awareness of ageism and faulty assumptions surrounding the competence of older adults. Additional considerations include elder abuse and exploitation, and isolation leading to loneliness and targeting by, for instance, “unscrupulous mailings and salespersons”. One participant, discussing the topic of lack of inclusion remarked, “I don’t want to be placed in the lobby with no interaction”. Some also highlighted the sense of helplessness and institutionalization that occurs in group homes, for instance, “living in a nursing home I have all my faculties. However, I tend to become ‘one of the crowd’ – as if I could not think on my own”.

The comments responding to the open-ended questions placed a particular emphasis on the principle of participation and inclusion. Participants complained about the increased helplessness and voicelessness that comes with aging – particularly for those in congregate settings. “I feel issues and needs are somewhat ignored. We are treated like toys”, noted one nursing-home resident; another participant made the typical observation that “you are old so you just have to put up with things as they are”. In a similar vein, many participants emphasized the isolation of older adults due either to having already lost family and friends, or, as one participant aptly noted, being “removed from the general population, [and being put] either in ‘adult’ or ‘seniors’ residences and communities or in nursing homes & as such, [becoming] more easily forgotten by the public”. These concerns were voiced most strenuously by rural seniors and persons with disabilities. The fear of most participants that they will “fall below the radar” was evident, and was apparent in many of their demands that legislators, and the public at large, should actively incorporate older adults into the community, as well as into the decision-making processes that affect their lives. A common piece of advice on this topic was that legislators and younger generations should “keep in mind that they will, one day, be older persons themselves…and these laws [or lack thereof] will also affect them.”

Comments relating to security generally emphasized financial security. “A safe place to live is sometimes a luxury” noted one of several respondents whose primary concern was financial security. Given their fixed incomes, older adults feared running out of money, coming to depend on their children, being unable to afford health and care services, and being unable to live comfortably in their old age.

3. Understanding the Needs and Circumstances of Older Adults

The programs and services that I use, and the rules and laws that I come into contact with take into account my circumstances as an older adult.

Comments about this question echoed those about the statement: “the public and private services and programs I use help me to achieve my goals as an older adult”. Respondents drew attention to a lack of wheelchair access in buildings, public transport, and roadways; a lack of information about various programs and services; and the lack of accessibility of political information and polling stations during elections.

The few positive comments noted the benefit of seniors’ discounts that increase access to programs and services.

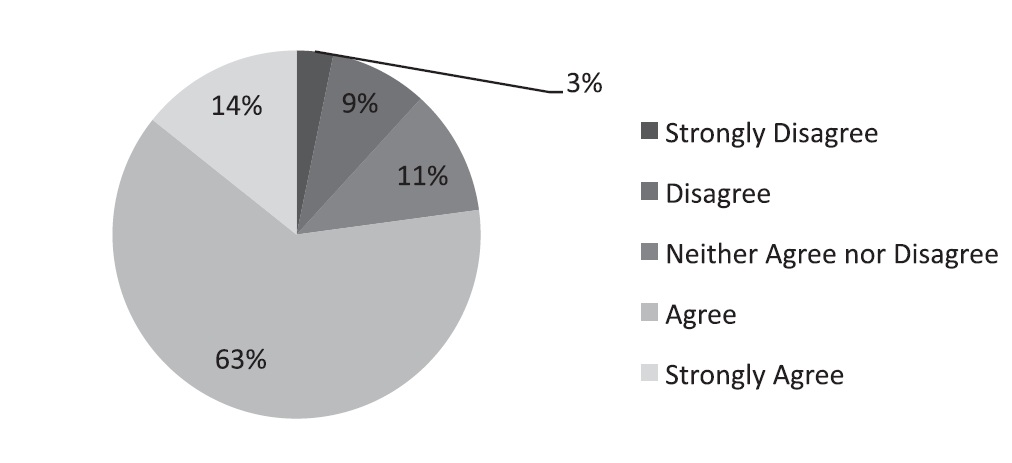

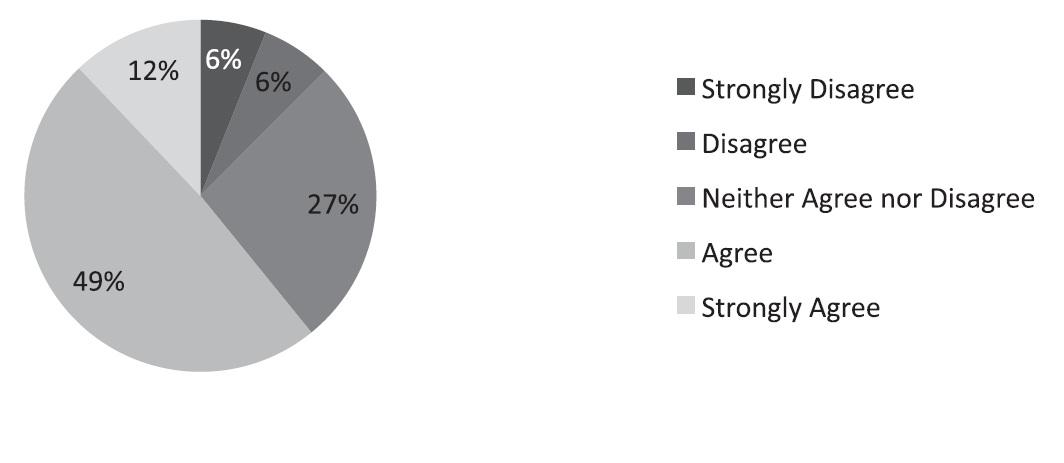

Individuals administering programs and services that affect older persons have the skill and the knowledge regarding age-related issues to do their work effectively

Respondents had mixed responses with respect to the above question. It was often noted that some individuals administering programs are competent and effective while others are not, as is reflected in the large percentage (29%) who neither agree nor disagree.

Responses focused on the performance of doctors, care-workers, and staff of long-term care and retirement homes. Respondents complained that these people often lacked the knowledge and skills to respond to the needs and frustrations of older adults, particularly those who have various disabilities and special needs. A large number of comments noted that hospitals, home care services and congregate settings are chronically understaffed and therefore incapable of properly attending to their responsibilities. This also causes lengthy wait-times.

In addition to being technically incompetent, respondents complained that care workers demonstrated a lack of emotional sensitivity manifested in impatience, impoliteness and disinterestedness. A couple of comments noted that it would be better if some of the individuals administering older adult programs and services, or making laws pertaining to older adults were themselves older adults, as they might then better appreciate their circumstances.

What would you like legislators and policy makers to understand about older persons when they are making or implementing programs, services or laws?

There were several main responses to this question. A common remark was that there is a need for adequate and accessible (both physically and financially) transportation, particularly for persons with disabilities. One participant aptly remarked, “if you can’t afford transportation, what value is the program being offered?”

Another theme from the responses emphasizes the need to provide increased opportunities for older adults to participate in the community, including: discounts for community activities; allowing older persons to continue working if they are able to; and being very mindful of the fact that many older adults are isolated and may therefore “fall beneath the radar”.

Respondents also emphasized a need to promote a shift in societal attitudes towards older persons, including recognizing ageism as a form of discrimination, and promoting more positive images of older persons as dignified, self-sufficient and competent individuals

A final key theme for this question was an emphasis on the need to integrate older adults into the legislative process. This includes the “need [for politicians] to visit long term care and retirement centres to see the conditions and situations for themselves before they make any decisions” and the “need to…have a committee of older adults for input prior to drawing up legislation”.

D. Enforcing Your Rights

I am well informed about my rights and the legal options available to me.

Respondents were frustrated about what they considered insufficient or overly complex information regarding their rights and legal options. They were frustrated also by their inability to obtain information over the internet, as well as the difficulty they experienced in obtaining information over the phone. For some, the problem is even more basic: they do not even “know the route to take to get the right person for assistance”. The telephone is clearly the primary means of communication for many older adults, and some participants were concerned about the difficulty of finding the right number to call to get information, navigating the automated systems, and then trying to explain their problems to impatient or incomprehensible agents. One frustrated respondent remarked, “how many buttons on the phone do you have to push to get the right person???”

Have you had an experience within the last five years where you felt your rights were being denied you?

Yes: 15% No: 85%

If you answered yes to the previous question, did you take steps to enforce your rights?

Yes: 71% No: 29%

If you answered yes to the previous question, was the experience a positive one?

Yes: 42% No: 58%

Those who answered “yes” to all three of the above questions did not go into detail about their experiences, but generally wrote something along the lines of, “I spoke to the person in authority and nothing happened”. One woman who lives in a nursing home explained that “issues and needs are just ignored; we are treated like toys”. No comments were provided by any of the respondents relating a positive experience of trying to exercise their rights.

What do you think is necessary for older adults to be able to enforce their rights?

The most common response to this question was “family and friends”. Other recurring responses included the suggestion of an ombudsman for older adults, and trustworthy doctors and lawyers. Other suggestions included a free seniors’ hotline that can provide information and advice; an older adults’ newsletter; periodic inspections in congregate settings by an independent observer with powers of investigation; and “money, determination, and moxie”.

| Previous | Next |

| First Page | Last Page |

| Table of Contents | |