I. Introduction

The Ontario government has requested that the Law Commission of Ontario (LCO) undertake a review of how adults with mental disabilities might be better enabled to participate in the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP). The LCO Board of Governors approved this project on Capacity of Adults with Mental Disabilities and the Federal RDSP in April 2013. The Ontario government announced its request and the LCO’s agreement to undertake the project in the 2013 Ontario Budget, A Prosperous and Fair Ontario, in May 2013.

Persons with disabilities tend to experience a lower standard of living than other Canadians due to factors such as barriers in the labour force and unmet needs for supports. The RDSP is a savings vehicle created by the federal government to assist persons with disabilities with long-term financial security. Financial institutions offer RDSPs to eligible members of the public. Beneficiaries and their family and friends can make private contributions to an RDSP. Beneficiaries can also receive government grants to match contributions and those with a low income may be eligible for government bonds.

The RDSP has distinctive policy objectives that include poverty alleviation, encouraging self-sufficiency and promoting the active involvement of persons with disabilities in making decisions that affect them. Under the Income Tax Act (ITA), adults can establish an RDSP for themselves and decide the plan terms as the “plan holder”. The ITA provides that where an adult is not “contractually competent to enter into a disability savings plan” with a financial institution, another “qualifying person” must act as a plan holder on his or her behalf.

A financial institution may decline to enter into an RDSP arrangement with a beneficiary who does not meet the common law test of capacity to enter into a contract. An adult or another interested person, such as a family member, may also believe that an adult has diminished capacity and wish to appoint a qualifying person before approaching a financial institution.

However, adults and their families have expressed concerns to the federal government with respect to provincial and territorial laws that govern how a qualifying person can be appointed. Many of these laws require that an adult be declared legally incapable and receive assistance from a guardian. This process can be expensive, time consuming and have significant repercussions for an adult’s well-being. In Ontario, qualifying persons include guardians and attorneys for property, who can be appointed under the Substitute Decisions Act, 1992 (SDA).

The Government of Ontario has recognized these concerns and has requested that the LCO undertake a review of how adults with mental disabilities might be better enabled to participate in the RDSP. The LCO’s project will recommend a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries that creates a streamlined alternative to Ontario’s current framework.

The purpose of this discussion paper is to synthesize the results of our preliminary research and consultations, and to identify several options for reform. Responses that we receive to this discussion paper will be considered for a Final Report with detailed recommendations.

The discussion paper identifies nine options for reform. The options draw on our review of Ontario’s framework under the SDA as well as other laws in Canada and abroad. They incorporate elements of existing laws that could meet evaluative criteria – or benchmarks – that the LCO has developed. We propose that an effective alternative process for Ontario would meet the following benchmarks:

- Responds to Individual Needs for RDSP Decision-Making

- Promotes Meaningful Inclusion in the Decision-Making Process

- Ensures that Necessary Protections for RDSP Beneficiaries are in Place

- Achieves Administrative Feasibility, Cost-Effectiveness and Ease of Use

- Provides Certainty to Legal Representatives and Third Parties

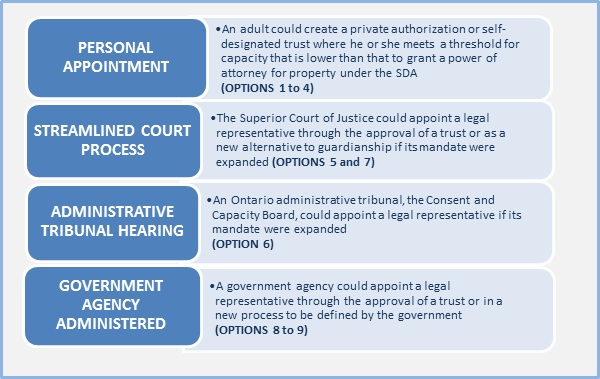

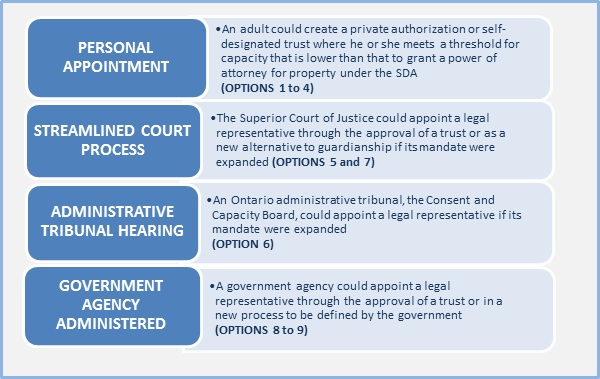

The options for reform are summarized further below in the Executive Summary. In total, we have proposed nine options that could be administered through the following overall types of processes to appoint a legal representative. We welcome comments on these types of appointment processes and the specific options for reform.

The options for reform in this discussion paper are a tailored response to the specific context of the RDSP. The LCO has reserved more comprehensive analysis of Ontario’s decision-making laws to its ongoing, multi-year project on Legal Capacity, Decision-Making and Guardianship. Our project concerning the RDSP is being delivered separately, on a priority basis, and it should not be construed as precluding any options in our larger project. For more information on the LCO’s project on Legal Capacity, Decision-Making and Guardianship, please visit the LCO’s website at www.lco-cdo.org.

II. Accessing the RDSP and Issues of Capacity for Ontarians with Mental Disabilities

Chapter II provides an overview of the RDSP and explains the importance of capacity when adults seek to access it. The first section in the chapter reviews contextual information on the RDSP that is relevant to the LCO’s project (Section A, Understanding the Federal RDSP). All persons who are entitled to the Disability Tax Credit (DTC) are eligible to become an RDSP beneficiary, if they are age 59 or under and resident in Canada when the RDSP is opened. RDSP beneficiaries come from diverse circumstances and they include persons with developmental, psychosocial and cognitive disabilities in all age groups.

The second section of Chapter II presents basic concepts and tensions that are relevant to defining capacity (Section B, The Importance of Capacity When Adults Seek to Access the RDSP). As mentioned above, opening an RDSP requires a plan holder to enter into a contract with a financial institution. Where an adult beneficiary is not “contractually competent to enter into a disability savings plan”, the ITA allows a qualifying person to be the plan holder. Qualifying persons can be a guardian or other person “who is legally authorized to act on behalf of the beneficiary”. Should Ontario create a new process to appoint a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries, he or she would likely need to be accepted by the federal government as “legally authorized” under provincial law, consistent with the language of the ITA.

Definitions of capacity vary across issue area and jurisdiction. In many jurisdictions, all human beings are presumed to be capable and are entitled to make decisions for themselves, unless it is believed that they are in need of protection. Although Ontario does not recognize “supported decision-making” formally in legislation as some jurisdictions do (see page xvi below), it has acknowledged that decision-making is a social and contextual activity, and that an adult’s capacity can be strengthened with services and supports.

An adult may have the capacity to make decisions relating to daily purchases but not, for instance, investing in a mutual fund. This is because capacity is specific to the issue at hand and it can fluctuate over time. There are various methods to determine if an adult has sufficient capacity to make a decision. The predominant method is the so-called “cognitive approach”, which focuses on assessing a person’s process of reasoning in coming to a particular decision. Another method that is accepted in some Canadian provinces is to consider non-cognitive factors, such as an adult’s ability to communicate wishes and preferences. This method reflects an express social policy objective to accommodate adults with significant mental disabilities who may have different ways of reaching and expressing their choices.

There are serious repercussions that result from a finding of incapacity, including restrictions on autonomy as well as stigma associated with the label of incapacity. Where a guardian is established through an external appointment process, such as a court proceeding, an adult may be found to be incapable of managing property. In Ontario, adults can personally appoint an attorney to act on their behalves without being found incapable, as long as they meet a standard for capacity to do so. In addition, certain external appoints do not require a finding of incapacity. For instance, an authorized person may be appointed where an adult has a demonstrated need for assistance in managing his or her finances.

Decision-making for the RDSP continues to be important throughout the RDSP life cycle. Depending on the RDSP plan terms, a plan holder may have authority to open the RDSP; authorize contributions; apply for government grants and bonds; decide terms for the investment of savings; and decide the availability, timing and amount of certain payments.

Plan holders do not automatically have authority to assist beneficiaries with all areas of RDSP decision-making. In particular, they are not authorized to assist a beneficiary in managing funds that have been paid out of the RDSP. The LCO heard in our preliminary consultations that some beneficiaries may also have a need for assistance with spending funds paid out of the RDSP. One issue that is addressed in this project is whether a legal representative’s scope of authority should be restricted to that of a full or partial plan holder, or extended beyond that of a plan holder to include managing RDSP payments made to the beneficiary.

III. Ontario’s Current Framework to Establish a Legal Representative for RDSP Beneficiaries

The SDA governs the establishment of general substitute decision-makers for property management, including through the execution of a power of attorney (POA) or the appointment of a guardian. Chapter III summarizes the SDA provisions that can be used to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries, although they are intended for broader application.

Under the SDA, an adult can execute a POA to appoint a person as a legal representative for the RDSP. The definition of capacity to grant a POA in Ontario is more stringent than in many other Canadian provinces. It is premised on a highly detailed, cognitive approach. If an adult does not have a valid POA and is not capable of granting one, a guardian can be appointed through court-based and statutory processes for an adult who is found to be incapable.

The LCO has received information on common challenges for beneficiaries and their families in establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries through available processes in Ontario and similar jurisdictions. These challenges are summarized immediately below and are discussed in Section III.C, Challenges Posed by Ontario’s Current Framework.

POWER OF ATTORNEY: Adults with mental disabilities may not be able to meet the threshold for capacity to execute a POA for property under the SDA.

COURT APPOINTMENT: The court-ordered guardianship process can be complex to navigate and may involve legal costs. It also requires that a person be found incapable of property management.

STATUTORY APPOINTMENT: Statutory guardianship can be easy to use and inexpensive. However, if there are complicating factors, it can become lengthy or finish before a judge. It also requires that a person be found incapable of property management.

GENERAL CONCERNS: Adults may have concerns about the degree to which they can be involved in decision-making activities once a substitute decision-maker is appointed under the SDA. Some adults also may not have access to a trusted family member or friend who can act as a guardian or attorney.

The LCO also received information from stakeholders with respect to various goals for reform that could respond to these challenges. The goals for reform are listed in Section D, Goals for Reform Identified by Stakeholders, and they have been integrated into our proposed benchmarks. We welcome your feedback on what you believe to be the challenges for RDSP beneficiaries and other interested parties, and the goals for reform for this project.

IV. Ontario’s Commitments to Persons with Mental Disabilities

Ontario’s commitments to persons with mental disabilities are found in laws, policies and programs. The most important domestic laws include the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Ontario Human Rights Code, and Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005. In addition, Canada has ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), subject to a Declaration and Reservation that it has submitted. The Government of Ontario has also created programs to deliver supports to persons with mental disabilities, including adults with diminished capacity. The service providers presented in Chapter IV consist of the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee, Consent and Capacity Board, Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP), and Community and Developmental Services.

We considered these laws, policies and programs in developing the benchmarks. Furthermore, existing service providers are considered for the role that they might play in the options for reform throughout the discussion paper.

V. Developing an Alternative Process to Establish a Legal Representative for RDSP Beneficiaries

Chapter V reviews and critically analyses laws in Ontario and other jurisdictions that provide insights into the development of an alternative process. Many of these are laws in Canadian provinces and territories that the federal government recognized in the Economic Action Plan 2012 as having instituted streamlined or other arrangements that could possibly address the concerns of RDSP beneficiaries.

The focus of Chapter V is on key issues that were identified repeatedly in our preliminary research and consultations. The key issues are found in Sections B through E, as indicated below. The first key issue, the choice of arrangements to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries, is the core issue for this project. It considers the general arrangement to designate a legal representative or to have one appointed. The other key issues consider aspects of any choice of arrangement that merit in-depth analysis. A summary of the options for reform for the key issues is contained at the end of each section.

Section B: Choice of Arrangements to Establish a Legal Representative for RDSP Beneficiaries

Section C: Roles and Responsibilities of the Adult, Legal Representative and Third Parties

Section D: Eligibility and Availability of Legal Representatives

Section E: Safeguards against Abuse and the Misuse of Legal Representative’s Powers

Section B examines existing arrangements in Canada and abroad, beginning with two provinces that have a specific process for the RDSP. We then consider laws in the areas of decision-making, trusts and the income support and social benefits sectors. The SDA is an example of a decision-making law. Other decision-making laws that we review provide for “special limited” POAs, supported decision-making, representation and designation agreements, co-decision making, streamlined court proceedings and administrative tribunal hearings. Trusts are a well-established method of assisting persons with disabilities in managing their assets. Under the law of trusts, we raise the question of whether an adult could designate a trustee to act as a legal representative for the RDSP or if a court could appoint a trustee on an adult’s behalf. Finally, we review arrangements that are embedded into income support and social benefits programs in order to enable a person to manage a recipient’s payments. Examples include what are commonly called “trustees” for the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and ODSP.

Section B concludes with a discussion of nine options for reform. The options draw on elements contained in existing arrangements but also take into account the benchmarks that a streamlined process in Ontario must meet to be effective.

Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements, provides a visual aid for readers and can be used as a point of reference for the key issue addressed in Section B (see pages 90 to 91).

The RDSP is a hybrid public and private initiative that requires the cooperation of multiple actors, including RDSP beneficiaries, their legal representatives and third parties, such as financial institutions. Section C examines the roles and responsibilities of these various actors with a focus on measures to ensure an RDSP beneficiary’s meaningful participation in decision-making, the liability of respective parties and the scope of a legal representative’s authority. The question of whether the scope of a legal representative’s authority should be restricted to that of a full or partial plan holder, or extended beyond that of a plan holder is an important issue for this project (see Section C.4, The Scope of a Legal Representative’s Authority).

Section D asks if organizations should be allowed to act as legal representatives for RDSP beneficiaries who do not have access to trusted family members or friends. In Section E, we review the risks of financial abuse in the context of the RDSP and measures to ensure that protections for beneficiaries are in place. Ontario’s framework to safeguard adults against financial abuse and the misuse of substitute decision-makers’ powers is relatively comprehensive when compared to other Canadian jurisdictions. Nonetheless, stakeholders have raised concerns that existing mechanisms are not sufficiently effective. Given that the RDSP attracts significant wealth, the LCO believes that supplemental measures may be desirable.

You are invited to consult Figure 3 for a summary of existing and possible additional safeguards reviewed in Section E (see page 129).

VI. Options for Reform

The discussion paper’s concluding Chapter VI brings together the options for reform identified at the end of each preceding chapter. It summarizes these options and discusses how they can be combined as well as implications for implementation. We also provide illustrative examples, so that readers can reflect on what the options might look like in practice.

The benefits and challenges that could flow from the options for reform are considered in Chapter VI and throughout the discussion paper. Only select observations are made here. If you would like to access more detailed information that is still summary in nature, you are invited to consult Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements, at pages 90 to 91.

Options 1 through 9, listed below, pertain to the core issue for this project, which is the choice of arrangements to establish a legal representative. The options can also be envisioned to incorporate features of the remaining key issues, including safeguards against abuse, and the roles and responsibilities of interested parties (see Chapter V).

OPTION 1: A private authorization granted by an adult who meets the common law threshold for capacity.

OPTION 2: A private authorization granted by an adult who meets non-cognitive criteria, such as the communication of desire and preferences.

OPTION 3: A private authorization granted by an adult who meets the common law threshold for capacity and who only needs support to make decisions for him or herself.

OPTION 4: A self-designated trust created by an adult who meets the common law threshold for capacity.

OPTION 5: An appointment made by the Superior Court of Justice if its mandate were expanded to facilitate an “alternative course of action” to guardianship.

OPTION 6: An appointment made by an administrative tribunal, the Consent and Capacity Board, if its mandate were expanded.

OPTION 7: An appointment made under the Superior Court of Justice’s jurisdiction over trusts.

OPTION 8: An appointment made at a government agency through the approval of a deed of trust.

OPTION 9: An appointment made at a government agency in a new process as defined by the government.

The figure on page ix of the Executive Summary is reproduced from Figure 4 in Chapter VI. It shows the overall types of appointment processes through which the nine options for reform could be delivered. In Ontario, both personal and external appointments are types of processes that exist under the SDA. Offering these two avenues to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries should be considered as a possible combination in the options for reform.

Personal appointments (Options 1 to 4) are generally perceived as preferable to external appointments because they are private, do not remove adults’ legal status as capable persons and allow them to proactively choose who they would like to assist them and how. Most of the personal appointments presented in the options for reform would require the acceptance of a less stringent threshold for capacity than that currently required in Ontario. This is because the LCO heard that the existing threshold for capacity to execute a POA for property under the SDA has been unattainable for many adults with mental disabilities wishing to access the RDSP. At this juncture in the project, the LCO has not received adequate information to determine if any one threshold would enable adults to overcome this barrier. Consequently, more evidence is required to understand if the options based on a new threshold for capacity would effectively meet the needs of RDSP beneficiaries.

The thresholds for capacity for personal appointments in the options for reform include cognitive (common law) and non-cognitive approaches. These two methods of determining capacity are discussed above in this Executive Summary (Section II). Option 3 is different from the other options that refer to the common law standard and requires explanation. It is modeled on supported decision-making arrangements in the Yukon and Alberta. Supported decision-making arrangements are available to adults who are capable of making decisions for themselves when they receive help. Unlike substitute decision-makers, such as an attorney or guardian, supporters are prohibited from making decisions on an adult’s behalf. They may undertake activities, such as accessing confidential information, giving advice and communicating an adult’s decision. In the Yukon, supported decision-making is available for personal care and financial matters. In Alberta, it is limited to personal care because of concerns that it could cause confusion and uncertainty in the context of financial transactions.

All arrangements that are established through a personal appointment could possibly also be established through an external appointment process, including substitute and supported decision-making (Options 5 to 9). Co-decision making is a further arrangement that has only been created through external appointments. Co-decision making is similar to supported decision-making insofar as it is available only to adults who can make decisions for themselves with assistance. However, co-decision making has an added degree of formality because the legal authority to make decisions is shared between the adult and co-decision maker. In transactions with third parties, a co-decision maker’s role may include signing documents jointly with the adult. In Saskatchewan, a court can appoint a co-decision maker for personal care and financial matters. Again, in Alberta, co-decision making does not apply to financial matters because of concerns that it could cause confusion and uncertainty in the context of financial transactions.

As shown above, an external appointment could be based on a new definition of capacity. An external appointment might also be premised on Ontario’s definition for incapacity to manage property under the SDA or on the determination of an adult’s need for assistance. In the discussion paper, we review laws in the income support and social benefits sectors that have a process to appoint a person to manage an adult’s payments where the adult has a demonstrated need for assistance. The LCO has heard that responding to an adult’s need for assistance could be less intrusive than an assessment for incapacity.

Streamlined court appointments are included among the types of processes in the options for reform (Options 5 and 7). The LCO recognizes that court proceedings tend to involve legal costs that could be prohibitive for adults and their families. We propose in the discussion paper that summary disposition applications that do not require a hearing before a judge could reduce legal costs. Enhanced support at the front-end of any court-based process from a government agency or community organization would be essential to make the process user-friendly and to secure an adult’s rights of due process.

Aside from the type of appointment process, the different areas of the law that the LCO has examined in the discussion paper also have particular benefits and challenges. In recent years, decision-making laws have received increased attention with the adoption of the CRPD and substantial law reform efforts in Canada and abroad. The LCO itself has an ongoing project on Legal Capacity, Decision-Making and Guardianship that comprehensively reviews decision-making laws in Ontario. Reforms to decision-making laws – including to the thresholds for capacity referred to above – would no doubt have normative value for the disability community. Moreover, they could involve creative solutions that expand on the mandates of the Superior Court of Justice or, if additional resources were provided, the Consent and Capacity Board (Options 5 and 6). However, an RDSP-specific process that is anchored in decision-making laws could create a disparity in entitlements to an alternative process that leaves out adults with diminished capacity for financial management who are not RDSP beneficiaries. Given the evolving state of the law, the ease with which the options in this area could be implemented in a timely manner is also an issue that merits attention. (Options 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6)

The law of trusts is valued for its adaptability to changing social objectives. In Ontario, trustees are held to standards that somewhat resemble those for substitute decision-makers. An adult can appoint a trustee where he or she can meet the common law threshold for capacity. Additionally, the courts have experience supervising the administration of trusts under the common law and statutes, such as the Trustee Act, Rules of Civil Procedure and Variation of Trusts Act. Trusts are, however, a complex area of the law. Funds in an RDSP may include mixed contributions from public and private sources, and it is unclear who would have legal authority to create a trust for the RDSP and to transfer the funds into trust. Furthermore, in order to achieve the benchmarks for reform proposed in this discussion paper, the adoption of minimum criteria relating to the key issues would be desirable. Clarity on these and other issues of implementation would be required for a trust mechanism to work. (Options 4, 7 and 8)

Options for reform that are modeled on the income support and social benefits sectors would provide RDSP beneficiaries with a streamlined process that is administered by staff members at a government agency. Similar to existing arrangements for ODSP and CPP recipients, an adult or another person could contact a designated government agency to initiate the appointment process. The government agency would then be charged with screening the legal representative, overseeing compliance and resolving disputes. Experiences with government agency administered arrangements in Canada and abroad demonstrate that they are resource intensive. The options for reform in this area of the law would necessarily entail the allocation of additional funding that the province may not have at present. (Options 8 and 9)

Following our summary of the options for reform in Chapter VI, we address several issues for implementation, which consist of the sources of government support, the provision of information to increase accessibility and coherence with other areas of the law (Section D, Important Issues for Implementation). One topic that we raise is whether the various options for reform might be grounded in legislation or implemented as a program or policy direction from the Government of Ontario. During the consultation phase for the project, the LCO would like to receive more information from the public on the preconditions to implement the options for reform and the opportunities for creative solutions.

We emphasize that the purpose of this discussion paper is to set a foundation for productive dialogue in the consultation phase for the project. The LCO has formulated the options for reform based on our preliminary research and consultations; however, they may not be exhaustive of the ways in which Ontario could respond to the challenges that beneficiaries face in establishing a legal representative for the RDSP. Therefore, in addition to the options raised in the discussion paper, we encourage your comments on further options that you believe will reasonably achieve the benchmarks for reform.

VII. How to Participate and Next Steps

Many of you have something of value to contribute to the LCO’s work. The LCO has prepared a list of questions for discussion on which we would like to hear your views. These questions are distributed throughout the discussion paper at the end of relevant sections and listed together in Appendix C, Questions for Discussion. We also invite you to give us your feedback on any other issues of interest through the means indicated in Chapter VII.

Based on the results of our consultation phase and the LCO’s ongoing research, the LCO will prepare a Final Report, which is anticipated to be released in Spring 2014.

| Next | |

| Last Page | |

| Table of Contents | |