Canada’s immigration system admits permanent residents in one of three ways: as economic immigrants bringing capital and labour skills that contribute to economic growth and community development, as sponsored family members for the purposes of family reunification, or as refugees on humanitarian grounds. The bulk of economic immigrants are higher-skilled workers who apply from outside of Canada and are assessed on a federally administered point system, business immigrants that include investors and entrepreneurs, and higher-skilled temporary workers and qualified international students already living in Canada who transition to permanent residency through the Canadian Experience Class.

PNPs represent a fourth pathway to permanent residency available to both higher and lower-skilled economic immigrants. These programs have developed in the context of an increasingly regionalized and decentralized immigration system in Canada, with the purposes of granting broader scope for provinces to tailor economic immigration in ways that meet their particular labour and overall economic development needs.

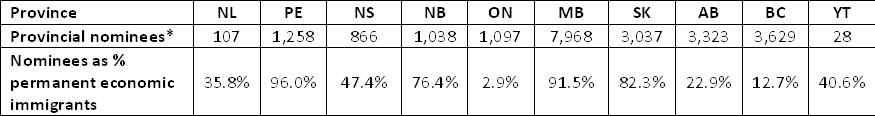

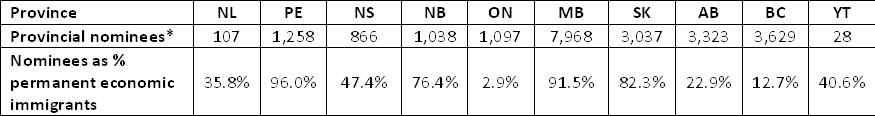

Provincial nominations for permanent residency in Canada emerged slowly in the late 1990s, but their popularity climbed steadily through the 2000s. Only 151 principle nominations were made in 1999, bringing a total of 477 immigrants, including spouses and dependents, to Canada through the PNP class in that year. By 2008, these numbers had climbed to 8,343 principle nominations and a total of PNP class 22,418 immigrants.[xxxvii] Manitoba led all other jurisdictions in PNP class immigrants in 2008, with 7,968 individuals – 34% of the Canadian total and more than double the number in British Columbia, the next most actively nominating province.[xxxviii]

As Table 3.1 makes clear, the quantitative significance of provincial nominees as a source of economic immigration varies considerably between provinces. In Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick, provincial nominees made up a relatively large proportion (75% or more) of the total permanent economic immigrants in 2008. By comparison, nominees were a less significant source of economic immigration overall in Alberta and British Columbia, despite the fact that these are among the provinces making the highest number of nominations per year. These two provinces also bring in the highest numbers of temporary foreign workers annually.[xxxix]

Table 3.1: Provincial Nominees in 2008

*Principle applications plus dependents

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Annual Report (2009).[xl]

Note, however, that these proportions are not necessarily an accurate reflection of why and how provincial nominees are economically, socially and/or demographically significant for each province. No data are available from CIC, for example, on what percentage of these nominees are high and low-skilled workers, or whether they are concentrated in particular industries. For provinces such as Ontario that do not currently admit low-skilled workers through their PNPs, the available data reflect only high-skilled workers. In the latter case, it would be safe to assume that PNPs in these provinces still play a relatively minor role in economic immigration overall.

Federal-provincial agreements on immigration undergird the recent shift toward greater provincial control over economic immigration and create the legal supra-structure for the PNPs. All ten provinces and the Yukon Territory have negotiated bilateral framework agreements with the federal government.[xli] The resulting PNPs form what amount to a series of decentralized channels through which private employers, via provincial governments, can access foreign labour and establish workers in long-term employment relationships as permanent residents. Some agreements also include provisions that may increase the flexibility of TFWPs to suit provincial purposes and provisions that delegate responsibilities for settlement services and immigrant protections to provincial governments and municipalities.

All of the federal-provincial agreements on immigration, not including the Canada-Quebec Accord, were signed or subsequently updated after the IRPA came into force in 2002.[xlii] These agreements define the responsibilities of respective federal and provincial governments in relation to new immigrants, temporary residents and refugees, and establish the terms of cooperation in each area.[xliii] The earliest of the current agreements was signed in 1996 (Manitoba) and the most recent in 2008 (Prince Edward Island). Most of the framework agreements have an indefinite duration, with the exception of British Columbia and Ontario, whose agreements are scheduled to expire in 2010.[xliv]

At the most general level, the federal-provincial framework agreements envision an allocation of immigration responsibilities along the following lines. The federal government retains primary control over setting national immigration policy by defining classes of admissibility and inadmissibility, and by ensuring that Canada meets its international obligations with respect to refugees.[xlv] The framework agreements then leave broad scope for provincial governments to shape decision-making processes and to directly select the individuals who will populate the provincial nominee class, with attention to social, economic, and demographic objectives defined by the provinces themselves. Notably, the federal government does not set a cap on the number of individuals nominated annually by the provinces, making room for the nominee class to become a very large box.[xlvi] The bulk of each agreement then goes on to define the terms of cooperation between the parties, with annexes providing for specific programs such as the PNPs and settlement services. Many provincial nominees will be individuals who initially entered the country with a temporary work permit under one of the federal TFWPs. Successful provincial nominees are fast-tracked through the immigration process in a fraction of the time that it would take them to gain permanent residency status via other federal immigration streams and are subject to special admission criteria designed by the responsible provincial government.[xlvii]

An early incarnation of the current nominee programs was negotiated by Manitoba in the mid-1990s as a response to labour shortages plaguing the province’s booming garment industry. At that time, public debates were ongoing between garment industry employers, who were pushing for greater flexibility to recruit foreign workers for permanent positions, mainly as sewing machine operators, and the Progressive Conservative provincial government of the day, which was generally in favour of preserving jobs for domestic labour. Eventually the garment industry employers won out.[xlviii] In 1996, Manitoba struck a deal with the federal government to recruit 200 foreign garment workers to settle permanently in the province.[xlix] Most of the workers recruited under this agreement were female sewing machine operators from the Philippines. The terms of the agreement placed stringent requirements on employers, requiring them to sponsor foreign garment workers, in the absence of family sponsorship, for a period of ten years. Employer sponsorship included responsibilities to ensure that workers did not access unemployment insurance or social assistance.[l] The actual degree of oversight or enforcement of sponsorship responsibilities has been called into question, however, as no government reports addressing this aspect of the agreement have ever been publically filed.[li]

Despite the Manitoba program’s early roots as a targeted labour migration scheme in lower-skilled sectors, recent trajectories suggest that its PNP has evolved as part of a much more broad-based regional immigration strategy.[lii] Some other provincial programs have developed along similar lines. New Brunswick, for example, implemented its PNP in 1999 as a mechanism to begin addressing long-term population decline, and to promote a more diverse population through immigration.[liii] As a result, the province’s early efforts through its PNP were largely directed toward higher-skilled economic immigrants and focused on attracting individuals to the main urban centres. Yet other provinces – British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in particular – appear to view their PNPs as a much narrower policy tool, using these programs in conjunction with the TFWPs to fill targeted labour shortages without addressing larger employment and immigration contexts. Finally provinces with newer programs that admit relatively few nominees, such as Ontario, have yet to define an over-arching policy direction. The implications of these divergent provincial approaches for lower-skilled temporary foreign workers are discussed in detail below.

3.1.1 General Features Common to PNPs

At least two features common to contemporary PNPs in Canada and relevant to lower-skilled foreign workers are discernable. First, provincial autonomy to develop and administer nominee programs under the framework agreements is nearly unlimited. According to all PNP agreements signed to date, provincial governments hold exclusive authority to establish program criteria, nomination quotas, and administrative schemes, leaving the federal government with a limited role to monitor basic admissibility requirements under the IRPA and to negotiate evaluation processes for each provincial program. The language of the framework agreements indicates unequivocally that these programs are designed for the provinces to occupy maximum jurisdictional space. The Canada-Ontario Agreement, for example, recognizes that “Ontario is best positioned to determine the specific needs of the province vis-à-vis immigration.”[liv] This and similar provisions represent a strong undercurrent pulling toward highly decentralized economic immigration programs.

At the level of program design, current PNP agreements enable the provinces to establish their own criteria for making nominations and to set target numbers for nominees from year to year.[lv] Most provinces have created distinct sub-categories or streams in their PNPs based on skill level, family statues, or planned business development, and sometimes restrict these to specific industries and occupations. Provinces do not require approval from CIC when they create or implement new streams or when they make changes to existing ones.[lvi] The PNP agreements also call for the federal and provincial governments to negotiate evaluation plans for each provincial program, but so far negotiations in this area have not been forthcoming, leaving the provinces effectively unrestrained in developing and modifying their programs.[lvii]

At the level of evaluating individual nomination applications, provincial governments, sometimes in partnership with employers and other non-governmental actors, are given the broad authority to make most, if not all, substantive determinations about eligibility. These parties process nominee applications and present a final nomination certificate to the CIC, which assesses basic individual admissibility requirements with respect to the health, criminality and security risk of the nominee.[lviii] Once the basic federal requirements are met, provincial nominees are normally approved and the necessary documents are issued by CIC to individual workers.

Notably, provinces may recommend that nominees be issued a temporary work permit, usually in the form of a permit renewal, without requiring an LMO. This process allows nominees to acquire a temporary work permit and continue working in the province while their application for permanent residency status is being processed. Some PNP agreements contain explicit language to recognize this power, but recent CIC Guidelines acknowledge the exemption for all provinces with PNP agreements in effect.[lix] Provincial needs to exercise this authority are also determined by the specific nomination requirements in place in each jurisdiction. All existing PNP streams for lower-skilled workers require nominees to first become temporary workers admitted into the province through one of the federal TFWP streams and to work under a temporary permit for a minimum time period before they are eligible to apply as a nominee (6 and 9 months are common). Other program steams for higher-skilled workers allow nominees to be recruited form outside Canada and to arrive directly without first applying through the TFWPs.[lx]

The reallocation of federal jurisdiction over immigration to the provinces has caused a growing divergence in the structure of nominee programs between provinces.[lxi] As Naomi Alboim and Maytree foreground in their recent report on Canada’s immigration system, the likely result of this trend is a fragmented policy landscape whereby provincial programs differ widely in their objectives and implementation strategies.[lxii] While fragmentation poses a serious barrier to developing a coherent national immigration policy, it also threatens to severely erode the abilities of provincial and federal governments to coordinate a system of labour protections and services for vulnerable lower-skilled foreign workers. This issue is taken up in more detail below.

A second common feature of PNPs is that they, like the TFWPs, are essentially employer-driven and thus reflect strongly the interests and demands of influential private actors. Employers directly generate the demand for foreign workers, sometimes participate actively in developing specific PNPs, and invariably exert a high degree of practical control over nominee recruitment and selection processes.

In a national study of employer practices, the Conference Board of Canada has found that employers are frequently turning to a combination of PNPs and TFWPs to meet their labour market requirements.[lxiii] For many of these employers, “it is increasingly difficult for them to attract and retain workers for certain positions due to growing skills and labour shortages, often tough and remote working conditions, and competition from other sectors.”[lxiv] The potential for PNPs to provide access to permanent immigrants whose employment skills are specifically selected to meet these labour requirements is clearly attractive to businesses. PNP immigration processes also tend to be much faster compared to those at the federal level, closing the sometimes-lengthy gap in time between the point at which employers identify labour needs and the point when workers are actually available to fill these positions. PNPs may also allow employers to bypass the federal LMO requirements under certain conditions, which is significant since employers have expressed some frustrations with the time and resources they need to devote to fulfill these requirements.[lxv]

But not all types of employers are equally likely to generate demand for provincial nominees. According to the Conference Board study, “[t]he PNP and the TFW Program are popular with some larger employers but often prove too costly for smaller ones to adopt.”[lxvi] Large businesses can more easily afford the significant administrative costs that can attach to recruiting, transporting, re-settling, and training nominees, such that the demands of these enterprises are most likely to dominate nominee programs. In a recent example, Maple Leaf Foods spent an estimated $7,000 per worker to employ individuals in their Brandon, Manitoba processing plant, bringing them to Canada initially through a TFWP and subsequently nominating them for permanent residency through the Manitoba PNP.[lxvii]

Notably, the federal-provincial agreements on immigration with Ontario and Alberta contain annexes that provide provincial governments and employers with greater flexibility in assessing labour market needs, without requiring input from HRSDC in the form of an LMO.[lxviii] The Ontario and Alberta annexes explicitly recognize that pursuant to s. 204(c) of the IRPR, CIC is authorized to issue a temporary work permit without requiring a prospective employer to seek an LMO if requested to do so by the province.[lxix] Under these sub-agreements, Ontario and Alberta agree to establish procedures and criteria to govern this authority, and to provide annual estimates of the number of temporary work permits issued by this route.[lxx]

The practical control that employers exert over nominee recruitment, selection and settlement processes is probably the most striking feature of the PNPs. Employers act as de facto principals for provincial nominees, selecting workers for nomination directly – sometimes through foreign recruiters as part of the TFWPs – and providing support and settlement services for them in Canada. For low-skilled employment positions, nominees are required in all PNPs to have worked for their nominating employer for a minimum period and to have obtained a permanent, long-term job offer prior to applying for nomination. Low-skilled employers too are often required to undertake specific responsibilities that heighten their level of involvement in many significant aspects of workers’ lives. These include facilitating the search for housing and providing for English or French language classes in cases where workers are not proficient in one of these languages.

A few critics of the TFWPs and PNPs in Canada have pointed out the overriding problem of employer control both in the policy-setting realm and in the actual workplace. Their criticisms raise concerns about effects on national immigration policy, on labour protection policies, on the realization of actual protections for vulnerable workers, or as some combination of these. In respect of immigration policy, “[s]ome argue that letting employers choose who enters is against all the principles that have shaped Canada as an immigration country.”[lxxi] These comments reflect deep-seated concerns about vesting private actors with core responsibilities for nation building.[lxxii] Alternatively, Alboim and Maytree target the devolution of decision-making and program development from the federal government to the provinces and private interests, resulting in fragmentation of immigration priorities and procedures.[lxxiii] Others have focused specifically on the fact the PNPs bind foreign workers closely to employers, exacerbating rather than relieving some of the real insecurities that figure prominently in the TFWPs.[lxxiv]

Some proponents of existing PNP models have countered that the problems associated with employer control over economic immigration are overstated and maintain that market-based incentives will effectively penalize abusive employers. These parties believe that economic immigrants will be attracted to responsible employers, such that employers will have adequate incentives to place voluntary restraints on formal and informal bargaining power.[lxxv] But this argument rests on the dubious assumption that information about employer practices is readily available and that it will be accessible by temporary foreign workers – who, as discussed below, face significant barriers related to language, education, cultural, and access to support services. Without this information, so-called “reputation effects” are unlikely to place serious restraints on employers’ actions. Overall, it is generally clear that implicit standards of self-regulation fall well below what is necessary to protect workers, particularly in light of the broad employer discretion now inherent in existing PNP models. The main questions, taken up in the following section, are about what aspects of nominee program design premised on this discretion actually contribute to workers’ insecurities and about whether responses by governments and third-party actors can be considered sufficient to meet the resulting concerns.

| Previous | Next |

| First Page | Last Page |

| Table of Contents | |