A. A Long-Term Savings Vehicle for Persons with Disabilities

The RDSP became available in December 2008 after several years of advocacy activities led by families of persons with disabilities and affiliated organizations.[21] The Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN), an organization founded by parents of children with disabilities, was instrumental in mobilizing broad-based discussions on how to secure the future well-being of children with severe disabilities, who would require funds as adults when their families would no longer be able to support them. With funding from the Law Foundation of British Columbia, PLAN commissioned two research studies to examine the viability of a savings plan for that purpose.[22] Following the submission of those studies to the federal government, the Minister of Finance appointed an Expert Panel that reviewed them and made further recommendations in its report, A New Beginning.[23] These recommendations were largely adopted in the design of the RDSP, including that all persons entitled to the Disability Tax Credit (DTC) would be eligible to become an RDSP beneficiary, both children and adults, age 59 and under.[24]

Figure 1: RDSP Quick Facts

- To become a beneficiary, a person must be eligible for the Disability Tax Credit, be a resident of Canada and be age 59 or under.

- The Canada Disability Savings Grant matches private contributions at rates of up to 300 per cent, depending on the amount of the contribution and family income (up to $3,500 annually and $70,000 over the beneficiary’s lifetime).

- The Canada Disability Savings Bond provides government support to those with a low income, depending on family income, even if they make no private contributions to the plan (up to $1,000 annually and $20,000 over the beneficiary’s lifetime).

- Funds in or withdrawn from an RDSP do not make beneficiaries ineligible for most provincial disability and income support programs, such as the ODSP, and they benefit from special treatment for tax purposes.

- When a beneficiary turns 60, mandatory periodic payments from the RDSP begin (called Lifetime Disability Assistance Payments or LDAPs).

- Beneficiaries can make one-time withdrawals, depending on rules set by the federal government (called Disability Assistance Payments or DAPs). However, withdrawals made within 10 years of receiving government contributions will reduce grants and bonds at a rate of three times (3x) the withdrawal amount.

We describe basic terms of the RDSP in the following sections. However, for more detailed information, please see the Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) website here: http://www.esdc.gc.ca/eng/disability/savings/index.shtml.

B. RDSP Policy Objectives: Poverty Alleviation, Contribution and Autonomy

The RDSP has distinctive policy objectives that are material to understanding its design and administration as well as adults’ expectations when they seek to access it. Although the LCO will not evaluate the RDSP policy objectives, or their implementation, we took them into account in defining the benchmarks for reform.

The RDSP is unique to Canada. The Minister of Finance’s Expert Panel surveyed a number of jurisdictions but “failed to turn up a form of tax assisted Disability Savings Plan that was in use in other countries”.[25] Without the benefit of an analogous example, the RDSP was modelled on other registered savings plans offered in Canada, such as the Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) and Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP).[26] This approach was consistent with PLAN’s earlier proposals, which had concluded that a tax-assisted savings plan would be the appropriate mechanism to achieve several policy objectives for the RDSP.[27] Long-term financial security for those who bear the high costs of disability was one such policy objective.[28] Other policy objectives included encouraging self-sufficiency through a contributory benefit structure,[29] promoting active citizenship as consumers of mainstream financial services, and developing a partnership among families, the government and the private sector “to share the responsibility for securing a good life for people with disabilities”.[30] These are discussed briefly below.

Families and governments often share responsibility to provide assistance to persons with disabilities. Family contributions may include caregiving in the tasks of daily living as well as financial assistance. These exist as informal supports within the naturally dynamic relationships that characterize family units and they complement government benefits.[31] Governments administer special programming for persons with disabilities, which is typically comprised of income supports and social services.[32] Social services include care and other assistance delivered by government and by voluntary and professional providers in areas such as homecare, equipment, therapy and employment training.[33]

In Canada, as elsewhere, income supports and social services have changed significantly over the last fifty years alongside a shift in the way that “disability” is conceptualized.[34] Services provided under earlier, wholly medical models of disability frequently entailed placing persons with disabilities in institutions that were removed from society in order to treat perceived impairments or for protection.[35] Beginning in the 1960s, social movements to deinstitutionalize persons with disabilities have emphasized participation and inclusion in community life. “Rather than seeing disability as inherent in an individual, these new approaches see disability resulting from attitudes and conditions within society”.[36] Public funds have been progressively reallocated away from institutions to income supports and community-based services.[37]

Many Canadians with disabilities now rely on income supports as their primary, if not only, source of income.[38] However, income support is intended only to cover the basic costs of living and supplemental benefits for disability-related services are often pre-determined.[39] Moreover, income supports in Canada have been found to hinder the contributions that adults can make to achieve varying levels of self-sufficiency.[40] The income support that Canada’s provinces administer to persons with disabilities is generally allocated as a monthly flat-rate and is “means-tested”: eligibility for income support requires that an adult has little independent income and, for each payment, there is a ceiling beyond which income that an adult generates, or the value of gifts, may be deducted.[41] In 2012, the Commission for the Review of Social Assistance in Ontario found that persons with disabilities, especially, “get trapped in the system and face diminishing opportunities….They are not receiving the support they need to stabilize their lives and move toward greater independence and resiliency”.[42]

The RDSP was conceived as a way to bridge the gap between the income support ceiling and the financial security required for an adult’s well-being, and it is exempted from means-testing under most provincial income support regulations, including in Ontario. An RDSP beneficiary can receive federal grants and bonds up to a maximum of $90,000 and accumulate additional savings of up to $200,000, before investments, without being subject to income support deductions.[43] As Professors Andrew Power and Janet Lord, and Allison DeFranco explain, “This is especially important because people with disabilities can now accumulate savings without jeopardising disability benefits”.[44]

The RDSP was also intended to enhance adults’ autonomy and equal citizenship as consumers of private sector products.[45] Recent reforms of government supports for persons with disabilities have increasingly tended toward establishing delivery mechanisms that empower adults to choose the assistance that they need for themselves.[46] This “personalisation of support”[47] has taken different forms across jurisdictions and may include “individual budgets, direct payments, consumer directed care, flexible funding and self-managed supports”.[48] The RDSP policy objectives are consistent with these recent reforms: “there are no restrictions on when [RDSP] funds can be used or for what purpose”.[49] RDSP funds are not limited to fulfilling basic needs, or to covering pre-determined services, which can “often take [on a] life of their own”.[50] Moreover, RDSP beneficiaries and their families are encouraged to make active contributions through the Canada Disability Savings Grant, which matches private deposits at rates of up to 300 per cent, depending on the amount of the deposit and the beneficiary’s family income (up to $3,500 annually). For those with low incomes, the Canada Disability Savings Bond provides government supports of up to $1,000 annually, even if no contributions are made to the plan. As with all contributions, these government supports can grow if the RDSP investments are fruitful.

In her study on the RDSP administration and uptake, Jeanette Moss summarizes these policy objectives as follows:

The RDSP signals an important shift away from a welfare-based approach to helping people with disabilities and moves towards an investment-based approach. Rather than increasing the amount of short-term disability benefits, the RDSP has the overarching purpose to provide a long-term sheltered savings vehicle. People with disabilities take an active role in their own income generation and future financial stability…. Rather than imposing a limit or ceiling on what people with disabilities can own or save, the RDSP establishes a foundation or starting place for people with disabilities to save money.[51]

C. Who Are RDSP Beneficiaries and How Do They Learn about the RDSP?

There are over 80,000 people in Canada with an RDSP.[52] RDSP beneficiaries must meet basic eligibility requirements set by the federal government, including that they must be a “DTC-eligible individual”.[53] Eligibility for the DTC is determined by the Canada Revenue Agency, based on certification by a “qualified practitioner” (such as a doctor, audiologist or occupational therapist, among others) that the individual applying for the DTC has “one or more severe and prolonged impairments in physical or mental functions” that affect his or her abilities to carry out basic activities of daily living in prescribed ways.[54] (The ITA provisions that define DTC eligibility are found in Appendix C.)

Within the bounds of these requirements, there is substantial diversity in the persons seeking to participate in the RDSP. Specific and actual beneficiaries identified in the LCO’s consultations and in submissions made to the federal government include persons with developmental, psychosocial and cognitive disabilities.[55] Some RDSP beneficiaries have lived with disability since birth, such as those persons with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), autism or Down syndrome. For others, changes in their abilities may have occurred later in life, such as those persons with schizophrenia, HIV/AIDS, acquired brain injuries (ABI) and Alzheimer’s disease.

The onset of disability may be abrupt or may develop gradually; abilities may be stable or they may fluctuate. The LCO heard from one RDSP beneficiary who said that not only does the RDSP help him save for when his family is no longer present, but it is also a contingency plan in the event that his abilities, services or support networks change: a “safety net” for the uncertainties that could “snowball” from his current situation.[56] We also heard that beneficiaries with degenerative conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis and developmental disabilities, may age at an accelerated rate and experience conditions normally associated with older adults, including dementia.[57] These accounts point to the need to consider the lived-experience of RDSP beneficiaries, including those who use the RDSP for reasons other than for long-term savings, because they face barriers in very different ways throughout their lives.

The effect of differing abilities on relationships, the nature of stigma associated with them, and the resources that are provided to separate communities all have a profound effect on how each individual accesses the RDSP. Accordingly, this project adopted “life course” and “person-centred” approaches to reviewing options for reform.[58]

In addition to disability, other common experiences and challenges are known. Both younger and older adults currently access the RDSP. RDSP funds are intended to be distributed primarily as mandatory lifetime disability assistance payments (LDAPs) that are released periodically once a beneficiary turns 60. Although there are few older adults receiving LDAPs at present, this will increasingly be the case as beneficiaries age. In Ontario, and the rest of Canada, persons over the age of 50 have withdrawn almost four times the number of payments than all other persons, totaling over $4 million in the five years since the RDSP was established.[59] Younger people may also face their own challenges when they transition into adulthood and become entitled to make decisions independent of a parent or guardian. The transition to adulthood may be felt acutely as young people take on new responsibilities. This has raised particular difficulties for children in state care who have had an RDSP opened on their behalf and who may need a legal representative when they transition away from child protection services.[60]

Adults learn about the RDSP at financial institutions and through various intermediaries. These entry points can involve the provision of information as well as advocacy assistance, such as professional financial advice or help with preparing applications for eligibility. Families and friends, including caregivers, are among the foremost entry points to the RDSP. Parents, spouses and common-law partners can temporarily qualify to open an RDSP on their loved one’s behalf through streamlined processes under the ITA, and often engage beneficiaries in informal shared decision-making on the plan terms.[61] Legal clinics habitually advise clients applying for, or receiving, ODSP about the RDSP, both individually and during educational workshops.[62] ODSP personnel have also directly informed recipients about the RDSP.[63] Eligibility criteria for the RDSP are not the same as for ODSP and the application processes are separate.[64] However, some adults may meet the eligibility criteria for both. Private trusts and estates lawyers also assist their clients in opening RDSPs in order to “shelter” funds, such as personal injury settlements, life insurance and inheritances, from taxation and to maintain ODSP eligibility by taking advantage of income and asset exemptions for the RDSP.[65] Community and advocacy organizations are active in raising awareness and assisting individuals seeking to access the RDSP.[66] Finally, adults have been targeted by companies whose core business is to prepare benefit applications for a fee.[67]

These entry points are as spread out as the services that adults use in their daily lives and they are more or less accessible, depending on the context. To the extent that entry points facilitate access to the RDSP, they are crucial to its delivery. The LCO’s recommendations consider how entry points can be leveraged to increase the accessibility of a process to establish an RDSP legal representative. In particular, we recommend that public information on a future process be distributed in accessible languages and formats through the individuals and organizations discussed above.

D. Opening and Managing an RDSP

1. Determining the Beneficiary’s Capacity to Be the Plan Holder

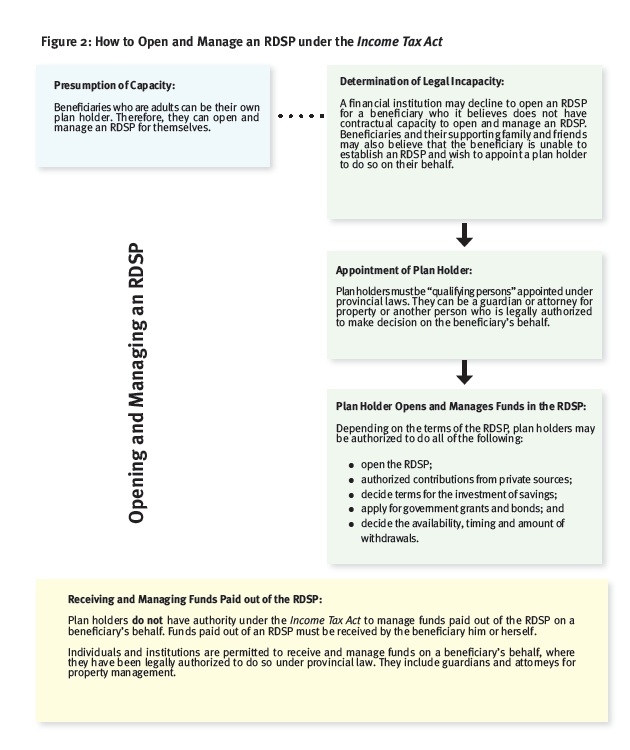

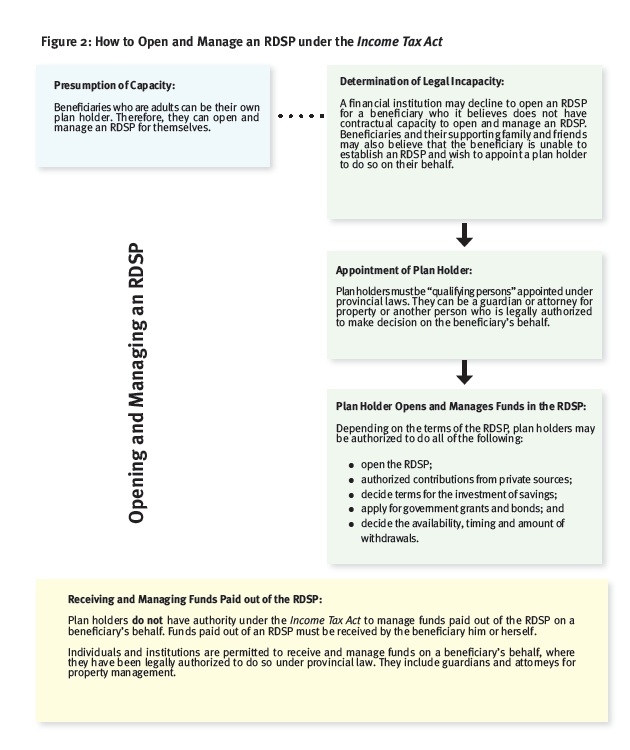

Every RDSP needs a plan holder, whether it is the beneficiary or another person. Opening an RDSP requires the plan holder to enter into a contract with a financial institution. If a beneficiary is an adult when the RDSP is being opened for the first time, he or she must be the plan holder. However, under the ITA, where a beneficiary is not “contractually competent to enter into a disability savings plan” with a financial institution, another “qualifying person” must be the plan holder. A qualifying person can be a guardian or other person “who is legally authorized to act on behalf of the beneficiary” under provincial laws.[68]

Entering into an RDSP contract with a beneficiary who is legally incapable of opening and managing a plan poses a risk both to the beneficiary and the financial institution. In Ontario, adults are presumed to be legally capable of entering into a contract and each contracting party is entitled to rely upon that presumption with respect to the other “unless he or she has reasonable grounds to believe that the other person is incapable of entering into a contract….”[69] An adult must be able to understand the nature and effect of the transaction to enter into a contract and if a party has actual or constructive knowledge that an adult is not able to meet this test, the contract could be voidable under the common law.[70] In its Report on Common Law Tests of Capacity, the British Columbia Law Institute explains that the law of capacity in this area attempts to strike an appropriate balance between protecting the adult’s interest and “the material interests of the other contracting party and the broader social interest in security of contracts”.[71]

Financial institution employees have declined to enter into contracts with beneficiaries whom they believe do not have legal capacity to open and manage an RDSP. The LCO has also learned that many beneficiaries and interested persons, such as family members, would themselves like to appoint a plan holder – before or after approaching a financial institution – because they believe that the beneficiary lacks legal capacity to be the plan holder.[72]

The LCO has consistently heard in our project that the structure of the RDSP program is complex and that decision-making for an RDSP can be demanding.[73] The RDSP is a financial vehicle that calls on plan holders to make educated decisions through traditional investment instruments, such as mutual funds. Even for individuals who do not face challenges with decision-making, financial literacy with these investments may require specialized advice from professionals, like investment advisors. In addition, the timing and amount of contributions and withdrawals have repercussions on a beneficiary’s entitlements that can be difficult to understand.

There may be individuals who disagree with a financial institution employee’s determination that they do not have legal capacity to be an RDSP plan holder and we address options for those individuals in Chapter IV.C.1, “Determining the Beneficiary’s Capacity to Be the Plan Holder”. However, we expect that the persons who have advocated for a streamlined process include adults with disability who believe they are unable to contract with a financial institution to open and manage an RDSP, and who would like someone else to do so for them.

The determination of legal capacity to be a plan holder, along with the other concerns discussed in this section, is depicted below in Figure 2: How to Open and Manage an RDSP under the Income Tax Act.

2. Responsibilities of the Plan Holder

The plan holder is the person who opens an RDSP by entering into a contract with a financial institution. However, the responsibilities of a plan holder do not end once an RDSP is established: a plan holder is responsible for making significant decisions about managing the plan throughout its lifecycle. Depending on the terms set out in the RDSP agreement with the financial institution, plan holders may have authority to do all of the following:

- open the RDSP;

- consent to contributions from private sources;

- decide terms for the investment of savings;

- apply for government grants and bonds; and

- decide the availability, timing and amount of withdrawals.

Plan holders have authority to decide how to invest the RDSP when it is first opened and can change investments at any time. They can also consent to private contributions being paid into the RDSP, and apply for government grants and bonds. Plan holders cannot make the initial decision to contribute funds to an RDSP on the contributor’s behalf. However, plan holders can consent to deposits being made into the RDSP because the timing of contributions is crucial to eligibility for the Canada Disability Savings Grant that is awarded to match contributions made within a calendar year up to a maximum amount.

Depending on the plan terms, plan holders also have authority to decide whether and when a beneficiary can receive one-time payments (called disability assistance payments or DAPs) and whether to start LDAP payments prior to their mandatory commencement date. The rules regarding the timing and calculation of withdrawals are highly detailed. Like those regarding contributions, they also carry serious consequences: although the government offers grants and bonds, should withdrawals occur during certain periods of time, this government support must be paid back threefold, which can significantly diminish RDSP funds.[74]

Plan holders are not authorized under the ITA to receive and manage funds paid out of an RDSP on a beneficiary’s behalf. We discuss issues surrounding the receipt and management of funds paid out of the RDSP in the next section.

For more information on the basic terms of the RDSP, see Figure 1: RDSP Quick Facts, above. We also suggest that you consult the ESDC website at: http://www.esdc.gc.ca/eng/disability/savings/index.shtml.

3. Receiving and Managing Funds Paid out of an RDSP

The ITA requires that an RDSP “be operated exclusively for the benefit of the beneficiary” and prohibits the surrender or assignment of payments to a person other than the beneficiary. Funds paid out of an RDSP must be received by the beneficiary him or herself, and plan holders are not authorized under the ITA to manage them on a beneficiary’s behalf.[75]

Funds paid out of an RDSP can be used for any purpose. A beneficiary could equally apply an RDSP payment to meet his or her basic needs, to purchase an assistive device, or to buy a movie ticket. This lack of restriction on the use of funds is consistent with the policy objectives underlying the RDSP, which include enhancing an adult’s autonomy, contribution and self-determination. However, it also means that funds paid out of an RDSP are an asset, like any other asset, and the range of decisions that can be made to spend RDSP funds is wide.

The LCO heard that while some beneficiaries may only need another person to manage funds in the RDSP, such as purchasing investment options, others may have a corresponding need when the time comes to spend money dispersed from the plan. The federal government permits legally authorized individuals or institutions, such as guardians and attorneys, to receive and manage funds on a beneficiary’s behalf, unless this is specifically disallowed by provincial laws.[76] The guardian or attorney could be the same person as the plan holder; however, he or she would have a different status under the ITA.

In recommending a process to appoint an RDSP legal representative who can open an RDSP and decide plan terms, one key issue in the LCO’s project has been to consider whether it would be appropriate to extend the scope of an RDSP legal representative’s authority beyond that of a plan holder to also include managing funds paid out of the RDSP (see Chapter IV.C.5, “The RDSP Legal Representative’s Role and Responsibilities”).

| Previous | Next |

| First Page | Last Page |

| Table of Contents | |