A. Understanding the Federal RDSP

1. A Long-Term Savings Vehicle for Persons with Disabilities

The RDSP was established after several years of advocacy activities led by families of persons with disabilities and affiliated organizations. The Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN), an organization founded by parents of children with disabilities, was instrumental in mobilizing broad-based discussions on how to secure the future well-being of children with severe disabilities, who would require funds as adults when their families would no longer be able to support them. With funding from the Law Foundation of British Columbia, PLAN commissioned two research studies to examine the viability of a savings plan for that purpose.[25] Following the submission of those studies to the federal government, the Minister of Finance appointed an Expert Panel that reviewed them and made further recommendations in its report A New Beginning.[26] These recommendations were largely adopted into the design of the RDSP, including that all persons entitled to the Disability Tax Credit (DTC) would be eligible to become an RDSP beneficiary, both children and adults, age 59 and under.[27]

The introduction of the RDSP was announced in the 2007 federal Budget, and it became available in December 2008.[28] The rules governing the RDSP, including eligibility criteria, plan terms, accountability measures and other issues are set out in the ITA, the Canada Disability Savings Act (CDSA)[29] and related Regulations. In October 2011, the federal government launched a review of the RDSP. In the course of that review, it raised the matter at issue in the LCO’s project. The federal government introduced a number of measures in the Economic Action Plan 2012, in response to feedback received during the review.[30] Parliament subsequently enacted several amendments to the ITA, including temporary provisions that are directly relevant to establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries.[31] Further consideration of the federal government’s review and legislative amendments is given later in this discussion paper in Chapter II.B, The Importance of Capacity When Adults Seek to Access the RDSP.

2. RDSP Policy Objectives: Poverty Alleviation, Contribution and Autonomy

The RDSP has distinctive policy objectives that are material to understanding its design and administration as well as adults’ expectations when they seek to access it. Although the LCO will not evaluate the RDSP policy objectives, or their implementation, we take them into account in defining the goals for reform.

The RDSP is unique to Canada. The Minister of Finance’s Expert Panel surveyed a number of jurisdictions but “failed to turn up a form of tax assisted Disability Savings Plan that was in use in other countries”.[32] Without the benefit of an analogous example, the RDSP was modelled on other registered savings plans offered in Canada, such as the Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) and Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP).[33] This approach was consistent with PLAN’s earlier proposals, which had concluded that a tax-assisted savings plan would be the appropriate mechanism to achieve several policy objectives for the RDSP.[34] Financial security for those who bear the high costs of disability was one such policy objective.[35] Other policy objectives included encouraging self-sufficiency through a contributory benefit structure,[36] promoting active citizenship as consumers of mainstream financial services, and developing a partnership among families, the government and the private sector “to share the responsibility for securing a good life for people with disabilities”.[37] These are discussed briefly below.

Families and governments often share responsibility to provide assistance to persons with disabilities. Family contributions may include caregiving in the tasks of daily living as well as financial assistance.[38] These exist as informal supports within the naturally dynamic relationships that characterize family units and they complement government benefits.[39] Governments administer special programming for persons with disabilities, which is typically comprised of income supports and social services.[40] Social services include care and other assistance delivered by government, voluntary and professional providers in areas such as homecare, equipment, therapy and employment training.[41]

In Canada, as elsewhere, income supports and social services have changed significantly over the last fifty years alongside a shift in the way that “disability” is conceptualized.[42] Services provided under earlier, wholly medical models of disability frequently entailed placing persons with disabilities in institutions that were removed from society in order to treat perceived impairments or for protection.[43] Beginning in the 1960s, social movements to deinstitutionalize persons with disabilities have emphasized participation and inclusion in community life. “Rather than seeing disability as inherent in an individual, these new approaches see disability resulting from attitudes and conditions within society”.[44] Public funds have been progressively reallocated away from institutions to income supports and community-based services.[45]

Many Canadians with disabilities now rely on income supports as their primary, if not only, source of income.[46] However, income support is intended only to cover the basic costs of living and supplemental benefits for disability-related services are often pre-determined.[47] Moreover, income supports in Canada have been found to disincentivize the contributions that adults can make to achieve varying levels of self-sufficiency.[48] The income support that Canada’s provinces administer to persons with disabilities is generally allocated as a monthly flat-rate and is “means-tested”: eligibility for income support requires that an adult has little independent income and for each payment, there is a ceiling beyond which income that an adult generates, or the value of gifts, may be deducted.[49] In 2012, the Commission for the Review of Social Assistance in Ontario found that persons with disabilities, especially, “get trapped in the system and face diminishing opportunities…They are not receiving the support they need to stabilize their lives and move toward greater independence and resiliency”.[50]

The RDSP was conceived as a way to bridge the gap between the income support ceiling and the financial security required for an adult’s well-being, and it is exempted from means-testing under most provincial income support regulations, including in Ontario. An RDSP beneficiary can receive federal grants and bonds up to a maximum of $90,000 and accumulate additional savings of up to $200,000, before investments, without being subject to income support deductions.[51] As Professor Andrew Power et al explain, “[t]his is especially important because people with disabilities can now accumulate savings without jeopardising disability benefits”.[52]

The RDSP was also intended to enhance adults’ autonomy and equal citizenship as consumers of private sector products.[53] Recent reforms of government supports for persons with disabilities have increasingly tended toward establishing delivery mechanisms that empower adults to choose the assistance that they need for themselves.[54] This “personalisation of support”[55] has taken different forms across jurisdictions and may include “individual budgets, direct payments, consumer directed care, flexible funding and self-managed supports”.[56] The RDSP policy objectives are consistent with these recent reforms: “there are no restrictions on when [RDSP] funds can be used or for what purpose”.[57] RDSP funds are not limited to fulfilling basic needs, or to covering pre-determined services, which can “often take [on a] life of their own”.[58] Moreover, RDSP beneficiaries and their families are encouraged to make active contributions through the Canada Disability Savings Grant, which matches private deposits at rates of up to 300 per cent, depending on the amount of the deposit and the beneficiary’s family income (up to $3,500 annually). For those with low incomes, the Canada Disability Savings Bond provides government supports of up to $1,000 annually, even if no contributions are made to the plan. As with all contributions, these government supports can grow if the RDSP investments are fruitful.

In her study on the RDSP administration and uptake, Jeanette Moss summarizes these policy objectives as follows:

The RDSP signals an important shift away from a welfare-based approach to helping people with disabilities and moves towards an investment-based approach. Rather than increasing the amount of short-term disability benefits, the RDSP has the overarching purpose to provide a long-term sheltered savings vehicle. People with disabilities take an active role in their own income generation and future financial stability…Rather than imposing a limit or ceiling on what people with disabilities can own or save, the RDSP establishes a foundation or starting place for people with disabilities to save money.[59]

3. Who are RDSP Beneficiaries and How Do They Access the RDSP?

There are over 70,000 people in Canada with an RDSP.[60] RDSP beneficiaries must meet basic eligibility requirements set by the federal government, including that they must be a “DTC-eligible individual”.[61] Within the bounds of these requirements, there is substantial diversity in the persons seeking to participate in the RDSP. Specific and actual beneficiaries identified in the LCO’s preliminary consultations and in submissions made to the federal government include persons with developmental, psychosocial and cognitive disabilities.[62] Some RDSP beneficiaries have lived with disability since birth, such as those persons with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), autism or Down syndrome. For others, changes in their abilities may have occurred later in life, such as those persons with schizophrenia, HIV/AIDS, acquired brain injuries (ABI) and Alzheimer’s disease.

The onset of disability may be abrupt or may develop gradually; abilities may be stable or they may fluctuate. The LCO heard from one RDSP beneficiary who said that not only does the RDSP help him save for when his family is no longer present, but it is also a contingency plan in the event that his abilities, services or support networks change: a “safety net” for the uncertainties that could “snowball” from his current situation.[63] We also heard that beneficiaries with degenerative conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis and developmental disabilities, may age at an accelerated rate and experience conditions normally associated with older adults, including dementia.[64] These accounts point to the need to consider the lived-experience of RDSP beneficiaries, including those who use the RDSP for reasons other than for long-term savings because they face barriers in very different ways throughout their lives.

The effect of differing abilities on relationships, the nature of stigma associated with them, and the resources that are provided to separate communities all have a profound effect on how each individual accesses the RDSP. Accordingly, this project has adopted “life course” and “person-centered” approaches to reviewing options for reform.[65] It is important that the project recognize and respect differences in abilities, gender, age, place of residence, income, culture, Aboriginal status, language proficiency and literacy, among intersecting identities, as well as identify the common experiences and challenges of RDSP beneficiaries.

In addition to disability, other common experiences and challenges are known. Both younger and older adults currently access the RDSP. RDSP funds are intended to be distributed primarily as mandatory lifetime disability assistance payments (LDAPs) that are released periodically once a beneficiary turns 60. Although there are few older adults receiving LDAPs at present, this will increasingly be the case as beneficiaries age. In Ontario, and the rest of Canada, persons over the age of 50 have withdrawn almost four times the number payments than all other persons, totaling over $4 million in the five years since the RDSP was established.[66] Younger people may also face their own challenges when they transition into adulthood and become entitled to make decisions independent of a parent or guardian. The transition to adulthood may be felt acutely as young people take on new responsibilities. This has raised particular difficulties for children in state care who have had an RDSP opened on their behalf and who may need a legal representative to assist them when they transition away from child protection services.[67]

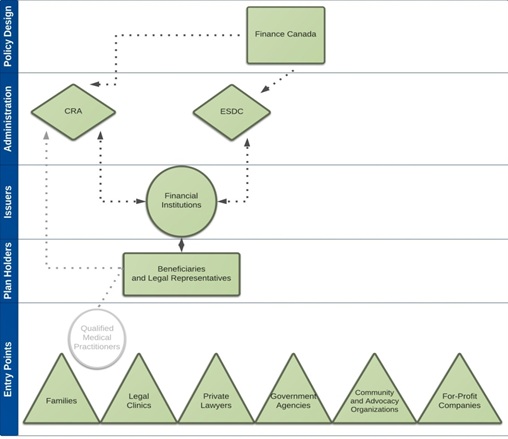

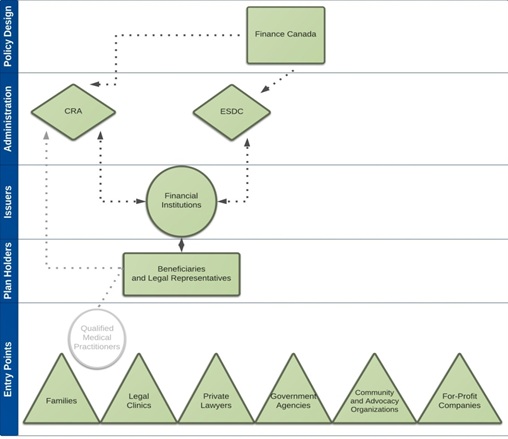

Adults learn about the RDSP at financial institutions and through various intermediaries. These entry points can involve the provision of information as well as advocacy assistance, such as professional financial advice or preparing applications for eligibility. Families and friends, including caregivers, are one of the foremost entry points to the RDSP. Parents, spouses and common-law partners can temporarily qualify to open an RDSP on their loved one’s behalf through streamlined processes under the ITA, and often engage beneficiaries in informal shared decision-making on the plan terms.[68] Legal clinics habitually advise clients applying for, or receiving, ODSP about the RDSP, both individually and during educational workshops.[69] ODSP personnel have also directly informed recipients about the RDSP.[70] Eligibility criteria for the RDSP are not the same as for ODSP and the application processes are separate.[71] However, some adults may meet the eligibility criteria for both. Private trusts and estates lawyers also assist their clients in opening RDSPs in order to “shelter” funds from personal injury settlements, life insurance and inheritances from taxation and to maintain ODSP eligibility by taking advantage of income and asset exemptions for the RDSP.[72] Community and advocacy organizations are active in raising awareness and assisting individuals seeking to access the RDSP.[73] Finally, adults have been targeted by companies whose core business is to prepare benefit applications for a fee.[74] Figure 1, Individuals and Organizations Involved in the RDSP Design and Delivery, situates entry points with other key individuals and organizations involved in the RDSP design and delivery.

These entry points are as spread out as the services that adults use in their daily lives and they are more or less accessible, depending on the context. To the extent that entry points facilitate access to the RDSP, they are crucial to its delivery. For instance, only 10.8 per cent of RDSPs are registered in rural areas of Canada,[75] where services are more remote. Chapter VI, Options for Reform, of this discussion paper addresses how entry points could be leveraged to increase the accessibility of a process to establish a legal representative.

4. Individuals and Organizations Involved in the RDSP Design and Delivery

The RDSP is a hybrid public and private initiative that requires the cooperation of actors across multiple sectors and levels. The federal government employed its fiscal powers to implement the RDSP under the ITA. The grants and bonds that are available to eligible beneficiaries as government contributions to the RDSP are regulated under the CDSA. Together, the ITA, CDSA and related Regulations, comprehensively address the RDSP eligibility criteria, plan conditions, accountability measures and other rules respecting administration under federal jurisdiction.

The Department of Finance Canada (Finance Canada) is responsible for developing the overall policy design of the RDSP. The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) are charged with administering the RDSP.[76] Both CRA and ESDC actively collaborate with financial institutions to register and monitor individual plans and they make policy recommendations to Finance Canada based on information gained in their respective roles. Overall, there is a high degree of information sharing among the federal departments and with financial institutions, all of whom are represented on an RDSP Advisory Committee that meets regularly.

An RDSP can be opened at a participating financial institution by a “plan holder”, who may be the beneficiary, or an entity legally authorized to act on his or her behalf. Once an RDSP is opened, plan holders have authority to determine important terms, such as the investment of RDSP funds, and the timing and amount of withdrawals.

Financial institutions are third parties who issue the RDSP and provide a point of contact in the relationship between beneficiaries, plan holders and the federal government. The RDSP is complex and involves high set-up costs; constant amendments also require extensive upgrades to financial institutions’ operations.[77] Financial institutions offer the RDSP voluntarily. Without them, the RDSP would not be available. Financial institutions offer the RDSP according to “specimen plans” that are approved by CRA. Specimen plans must conform to the statutory RDSP rules but vary according to each financial institutions’ terms.[78] Financial institutions are required to report data on individual RDSPs to ESDC and CRA, including monthly accountings of savings, withdrawals and investment activity.[79]

To be DTC-eligible, every RDSP beneficiary must undergo a medical assessment. As a result, each adult will encounter a practitioner qualified to conduct an assessment. “Qualified practitioners” include medical doctors, audiologists, occupational therapists, and other medical and paramedical professionals, who fill in a DTC Certificate as prescribed under the ITA.[80] Similar to financial institutions, they embody an axis point that all beneficiaries must pass, or have passed, through when applying for the RDSP.

FIGURE 1: INDIVIDUALS AND ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN THE RDSP DESIGN AND DELIVERY

CRA: Canada Revenue Agency

ESDC: Employment and Social Development Canada

Figure 1 illustrates the interaction of individuals and organizations involved in the design and delivery of the RDSP along the left bar by: 1. entry points, 2. plan holders, 3. issuers, 4. administrators and 5. policy designers. Qualified medical practitioners are set apart because eligibility for the DTC is determined separately from activities in the RDSP administration.

Relationships among the actors involved in the RDSP design and delivery are complex and highly regulated. For this reason, any options for reform must respond to existing operational and policy constraints that lie beyond the ambit of the LCO’s review. Because of the limited scope of this project, this discussion paper primarily addresses the roles and responsibilities of individuals and organizations represented in the bottom three tiers of Figure 1 in addition to those of the Government of Ontario.

B. The Importance of Capacity When Adults Seek to Access the RDSP

1. Capacity Laws as a Barrier to Accessing the RDSP

Opening an RDSP requires a plan holder to enter into a contract with a financial institution.[81] During its 2011 review of the RDSP, the federal government reported that “a number of adults with disabilities have experienced problems in establishing a plan as the nature of their disability precludes them from entering into a contract”.[82] If a beneficiary is an adult when the RDSP is being opened for the first time, the beneficiary is the plan holder unless he or she is not legally capable of entering into a contract with a financial institution.[83]A financial institution may decline to enter into an RDSP arrangement with a beneficiary who does not meet the common law test of capacity to enter into a contract.[84] An adult or another interested person, such as a family member, may also believe that an adult has diminished capacity to enter into an RDSP arrangement and wish to appoint a person to assist even before approaching a financial institution.

Where an adult beneficiary is not “contractually competent to enter into a disability savings plan” with a financial institution, the ITA allows another “qualifying person” to be the plan holder.[85] Qualifying persons can be a guardian or other person “who is legally authorized to act on behalf of the beneficiary”.[86] The ITA does not provide for a process to appoint a guardian or other person who is legally authorized to act on behalf of the RDSP beneficiary. The federal government has stated that “[q]uestions of appropriate legal representation in these cases are a matter of provincial and territorial responsibility”.[87] In Ontario, guardians and attorneys for property are qualifying persons who can be appointed under the SDA.

In the course of its 2011 review of the RDSP, beneficiaries and their families voiced concerns to the federal government with respect to existing frameworks within provincial jurisdictions, many of which require “the individual to be declared legally incompetent and have someone named as their legal guardian”.[88] In the Economic Action Plan 2012, the federal government also reported specific concerns that such “a process…can involve a considerable amount of time and expense on the part of concerned family members, and…may have significant repercussions for the individual”.[89]

The federal government amended the ITA in response to these concerns, albeit temporarily and to a limited extent. The amendments to the ITA expand the definition of qualifying persons to include a “qualifying family member”, who can act on behalf of the adult beneficiary where “in the [financial institution’s] opinion after reasonable inquiry, the beneficiary’s contractual competence to enter into a disability savings plan at that time is in doubt”.[90] Qualifying family members, who can act as plan holders, are restricted to a small class of persons, namely, spouses, common-law partners and legal parents. The federal government’s temporary measure will expire at the end of 2016.

Under the ITA, a beneficiary can replace a qualifying person as a plan holder where the beneficiary so chooses and he or she has been determined to be “contractually competent” by a “competent tribunal or other authority” under provincial law or if, in the financial institution’s opinion, the beneficiary’s capacity is no longer in doubt.[91] In Ontario, an adult could refute a financial institution’s opinion regarding his or her capacity to enter into a contract by requesting an assessment by a certified capacity assessor. The capacity assessment process, including costs and possible implications, is reviewed in Chapter III.B.3, Statutory Guardianship Appointments.

The purpose of this project is to recommend a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries who experience diminished capacity that is an accessible alternative to Ontario’s current framework to appoint a guardian or attorney for property. Should Ontario adopt a new process to appoint a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries, it must be consistent with the provisions of the ITA. As a result, a legal representative would likely need to be accepted by the federal government as a person “who is legally authorized to act on behalf of the beneficiary” under provincial law, as described above.[92]

2. Critical Times for Decision-Making: Opening the RDSP, Deciding Plan Terms and Managing Funds that Have Been Paid Out of the RDSP

The RDSP is a financial vehicle that calls on plan holders to make educated decisions through traditional investment instruments, such as mutual funds. Even for individuals who do not face challenges with property management, financial literacy may require specialized support from professionals, like investment advisors. The public regularly receives these supports for other types of registered plans, such as RRSPs and RESPs. However, in addition to such investment decisions, the LCO heard from stakeholders that the structure of the RDSP is complex and decision-making for the RDSP is demanding.[93]

The temporary amendments to the ITA create only a small category of legal representatives – spouses, common-law partners and parents – whose scope of authority is limited to being an RDSP plan holder. A plan holder has authority to do all the following:

- open the RDSP at a financial institution

- authorize contributions from private sources

- apply for government grants and bonds

- decide terms for the investment of savings; and

- depending on the plan terms, decide the availability, timing and amount of payments

A plan holder has authority to decide how to invest the RDSP when it is first opened, and can change investments throughout the RDSP life cycle. A plan holder can also authorize private contributions to the RDSP, and apply for government grants and bonds. The timing of contributions is crucial to eligibility for the Canada Disability Saving Grant because the grant is awarded to match contributions made within a calendar year.

Depending on the plan terms, a plan holder also has authority to decide whether and when a beneficiary can receive one-time payments (called disability assistance payments or “DAPs”) and whether to start LDAP payments prior to their mandatory commencement date. The rules regarding the timing and calculation of withdrawals are highly detailed. They also carry serious consequences: although the government offers grants and bonds to beneficiaries, should withdrawals occur during certain periods of time, government support must be paid back, which can significantly diminish RDSP funds.[94]

The plan holder is not automatically authorized to assist a beneficiary in managing his or her DAP or LDAP funds once they are dispersed from the plan. Funds paid out of an RDSP can be used for any purpose. A beneficiary could equally apply an RDSP payment to meet his or her basic needs, to purchase an assistive device, or to buy a movie ticket. This means that the RDSP is an asset, like any other asset, and that the range of decisions that can be made to spend RDSP funds is wide.

Because plan holders are not authorized to assist in making decisions once funds are dispersed, if a beneficiary lacks capacity, she or he may be required to receive additional assistance from a guardian or other substitute decision-maker established under provincial or territorial statute, such as Ontario’s SDA. That legal representative could be the plan holder or another individual or organization, but must be appointed to this role in a separate process. One key issue in the LCO’s project is to consider whether a legal representative’s scope of authority should be limited to that of a full or partial plan holder, or extended beyond that of a plan holder to also include managing RDSP payments made to the beneficiary (see Chapter V.C.4, The Scope of a Legal Representative’s Authority).

3. What is Capacity? Foundational Concepts and Tensions

a. Introduction

The history of capacity laws is long, complex and still evolving, and it cannot be comprehensively reviewed here.[95] This discussion paper is squarely concerned with the importance of capacity when adults with mental disabilities seek to access the RDSP. This section presents basic concepts and tensions that are relevant to defining capacity for RDSP decision-making.

b. Capacity as a Socio-Legal Concept

Capacity is a socio-legal concept that has a significant impact on our lives because it determines who is entitled to make decisions that the law recognizes as valid. Capacity laws create a threshold beyond which a person may be restricted from making essential decisions independently, such as deciding where to live, consenting to healthcare or opening an RDSP.

However, capacity laws do not always negate rights and can empower them instead. In Ontario, we are presumed to be capable in our interactions with others and can enter into arrangements without coercion.[96] Moreover, we access various services in our daily lives that assist us in reaching decisions without being found to be incapable, as where we receive investment advice from a financial planner. In this sense, the law recognizes both protections and supports, and we are all affected by how it defines capacity.

Legal definitions of capacity vary widely across issue area and jurisdiction. The capacity to execute a will, to consent to marriage or to manage one’s property may be defined according to different standards as between or, even, within particular jurisdictions. In the case of the RDSP, the current legal framework counts more than one source to define capacity and more than one assessment standard.

While some regard capacity – particularly the related term “mental competency”[97] – as a medical certitude, others have argued that “incapacity exists only after we define it”;[98] that it is fundamentally a “legal fiction”.[99] Consistent with past approaches in the expert literature and commissioned enquiries, including in Ontario, the LCO recognizes that capacity is fundamentally a “socio-legal concept”.[100] This is to say that laws regulate the meaning of capacity to achieve goals that are informed by prevailing social needs and values.

It is important to appreciate the nature of capacity as reflecting social needs and values because it explains why it changes over issue area, time and place, and can continue to do so.[101] However, definitions of capacity are often “treated as fact” in implementing the law and, in any given place or time in history, capacity does not lack consequences for those who are affected.[102]

c. Social Needs and Values Underlying Definitions of Capacity

As discussed later in this subsection, the LCO Framework Principles recognize a nuanced understanding of the social needs and values underlying the concept of capacity, and the social nature of the decision-making process. The predominant characterization of these social needs and values, however, is as a balance between autonomy and protection.[103] The presumption of capacity accepts that all human beings are equally entitled to make decisions for themselves as autonomous actors, unless it is believed that they cannot exercise autonomy and are in need of protection.[104] Contemporary accounts largely describe autonomy as self-determination, independence and freedom from coercion. As such, it relates to “the process of self-rule making, rather than the content of the rules made, [and] avoids assigning social values to particular choices and ways of living….”[105] Autonomy concerns agency in the exercise of one’s choices, and is thus connected to concepts of personal integrity and the right to take risks, even if others believe them to be imprudent.[106]

The strong value assigned to autonomy is enshrined in international human rights treaties, such as those that succeeded the atrocities of World War II, as well as in constitutional and human rights laws at the domestic level, and it can be traced back to libertarian ideals that arose out of the “more status oriented structures which were dominant in pre-literate, feudal societies”.[107] In the area of decision-making law, the value of autonomy has been central to disentangling assumptions that correlate disability status with incapacity in favour of understanding the functional process that adults undertake to make particular decisions. Margaret Hall explains the relationship between autonomy and capacity as follows:

Capacity, in law, serves as the effective threshold of autonomy, dividing the autonomy, on the one side, from the “non-autonomous” persons, “on the basis of an individual’s ability to engage in the process of rational (and therefore autonomous) thought, explained as the ability to exercise one’s own will to reflect upon, and choose between desires, and to adopt those chosen as one’s “own”.[108]

On the other end of the continuum of social needs and values is protection through intervention. Protection is a form of risk management for adults who face challenges in decision-making as well as the greater community affected by their actions.[109] Whereas autonomy is said to be value-neutral on the substance of decisions, protection is premised on the perception of risk to the well-being of decision-makers and those around them.

Where it is the adult who is being protected, at least two broad justifications have been used to negate the preference for autonomy. Interventions have been justified where it is believed that an adult is unable to act in his or her own “best interests”.[110] Interventions have also been justified on the basis that an adult faces challenges in his or her ability to rationally comprehend and communicate choices.[111] Underlying both these justifications is the perception that an adult may suffer harm from self-neglect or increased vulnerability to potential mistreatment, abuse and exploitation. The LCO heard from stakeholders that protecting adults from harm is a real and pressing need and that neglecting to do so could seriously undermine the dignity of adults who are unable to care for themselves.

Where the greater community is being protected, interventions are justified by a number of social needs and values. Beyond the threat of injury to other persons – which is the domain of criminal and mental health laws not considered in this project – at least two community interests are relevant here. Third parties who engage in legal arrangements have an interest in ensuring that they are valid. For example, financial institutions can suffer losses where they enter into a contract with an adult who is legally incapable because the common law protects the adult from unfair transactions by making the contract voidable.[112] Along the same lines, protecting third parties from invalid legal arrangements is a way to promote autonomy for those same third parties because it frees them from doubts about the enforceability of their choices.[113] Additionally, the government has an interest in defining legal capacity to safeguard relationships among its citizens so as to lower transaction costs, promote efficiencies and maintain an “administratively workable community”.[114]

The predominant characterization of capacity as a balance between autonomy and protection has been subject to the critique that it dichotomizes a more nuanced picture of social needs and values.[115] For example, some say that protection can actually serve to facilitate, rather than inhibit, autonomy through the provision of accommodations. In such cases, interventions based on incapacity could be avoided if the assistance provided enables adults to overcome barriers to decision-making to sufficiently reduce the risk of harm.[116]

At the root of this critique is the reimagining of autonomy as something other than one individual’s ability to make decisions independently.[117] Many theorists, community organizations and governments have come to value decision-making as a social and contextual process, drawing on a theory that feminist critical thinkers call “relational autonomy”.[118] The Office of the Public Advocate for Victoria, Australia observes that

Most people in the community seek the support of others in making significant decisions about their lives. In modern society there is a high level of dependence on the expertise and knowledge of those with special qualifications, skill and talents depending on the sorts of decisions that a person is faced with. In addition, people talk about their choices with others and on the advice of others and few decisions, especially about important matters, are made in isolation. In our society, relying on the advice of others is not seen as an indication that a person lacks the mental capacity to make his or her own decisions.

It is therefore argued that the idea of the independent, autonomous decision-maker, at least as far as the process of decision-making is concerned, is a myth and that interdependent decision making is the way in which most of us operate. The amount of support and assistance people seek and receive to make decisions varies, depending on a person’s ability, personality and life circumstances and on the particular decision.[119]

Relational autonomy is also connected to other ways of conceptualizing social needs and values that underlie definitions of capacity, including the developmental (rather than static and fixed) nature of autonomy;[120] culturally appropriate decision-making;[121] a deeper understanding of personhood beyond rational thinking[122] and respect for human dignity.[123] Laws in certain jurisdictions and recent law reform reports on decision-making indicate an acceptance of nuanced social needs and values, for instance, in adopting detailed sets of principles.[124]

The LCO’s Framework Principles recognize the social and contextual nature of the decision-making process (see Appendix B). In A Framework for the Law as it Affects Persons with Disabilities, the principle of “Fostering Autonomy and Independence” refers to the creation of conditions to ensure that persons with disabilities are “able to make choices that affect their lives and to do as much for themselves as possible or as they desire, with appropriate and adequate supports as required [emphasis added]”. The Framework Principles also recognize “Facilitating the Right to Live in Safety”, which consists of “the right of persons with disabilities to live without fear of abuse or exploitation and where appropriate to receive support in making decisions that could have an impact on safety”. In addition, the LCO acknowledges “that other members of society also have entitlements and responsibilities” under the principle of “Recognizing That We All Live in Society”. The remaining Framework Principles include “Promoting Social Inclusion and Participation”, “Responding to Diversity in Human Abilities and Other Characteristics” and “Respecting the Dignity and Worth of Persons with Disabilities”.[125]

d. Methods to Determine an Adult’s Capacity or Incapacity

Methods to determine an adult’s capacity or incapacity are heavily influenced by the social needs and values that underpin the concept of capacity, such as those mentioned above. The predominant contemporary method to determine capacity or incapacity has evolved over time with a view to enhancing an adult’s autonomy, reducing paternalism while safeguarding against harm, and protecting the competing interests of affected third parties. This so-called “cognitive approach” typically involves assessing the adult’s process of reasoning in coming to a particular decision. Thus, it focuses on “a person’s ability to perform a specified function, such as understanding the nature of a contract”.[126] The Queensland Law Reform Commission has described the approach as follows:

The functional approach is based on cognitive (functional) ability to make a specific decision, including a specific type of decision, at the time the decision is to be made. It focuses on the reasoning process involved in making decisions. This encapsulates the abilities to understand, retain and evaluate the information relevant to the decision (including its likely consequences) and to weigh that information in the balance to reach a decision.[127]

The cognitive approach is considered to be “consistent with the principle of least restriction for an adult in making decisions because it involves proportionate and minimal intrusion on decision-making autonomy”.[128] In contrast to historical approaches, it rejects the bright-line assumption that persons with disabilities do not have the capacity to act autonomously and are in need of protection. It allows persons to make risky decisions that some might view as imprudent based on opinion. Moreover, it accommodates issue-specific and fluctuating abilities by restricting the attribution of incapacity to particular areas of decision-making, for instance through the separation of property management and personal care.[129]

Despite commonly perceived gains made to promote autonomy under the cognitive approach, some argue that testing an adult’s cognitive ability is discriminatory because it disproportionality disadvantages persons with mental disabilities, who may have different ways of reaching and expressing choices.[130] Bach and Kerzner suggest that this approach should be reformed to encourage a “more inclusive concept of personhood than that defined by the criteria of rationality so pervasive in legal incapacity law”.[131] Their suggested threshold for what they call “decision-making ability” is comprised of two criteria: the capacity to express one’s will and/or intentions; and the ability for one’s life story of values, aims, needs and challenges to be understood by others, who can then help give effect to one’s will and/or intentions. They claim that behaviour and communications, such as utterances and gestures, can be used to interpret a person’s decision under this method.[132]

Bach and Kerzner’s proposal resembles methods to determine capacity in two Canadian provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador and British Columbia. It is also common across jurisdictions for an adult’s non-cognitive expressions of preference, wishes, emotion and values to be considered valid indicators of choice in guiding substitute decision-makers after they have been established.[133] The LCO will consider methods to determine capacity in the provinces named above along with the predominant functional approach in Chapter V.B, Choice of Arrangements to Establish a Legal Representative for the RDSP.

e. Using the Language of Capacity or Incapacity: Qualifiers and Disqualifiers

The social needs and values that are promoted in capacity laws can be met through a finding of incapacity or the recognition of a specified level of capacity. For instance, a court may appoint a guardian after finding an adult to be incapable of managing property. An adult may also appoint an attorney to give effect to his or her wishes as long as he or she meets a standard for capacity to do so.

There are normative and practical consequences that result from determining capacity instead of incapacity. Canada, joined by 157 countries in the international community, has recognized the tremendous significance that adults with disabilities attribute to being accepted as capable persons under the law.[134] The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities guarantees them the enjoyment of legal capacity on an equal basis with all others. It enumerates prescribed rights to supports and accommodations with a view to empowering persons with diminished capacity, and adopts principles of minimal intrusion. These advances must be understood in the context of how the concept of capacity has been used historically to exclude various groups from entitlements to basic civil rights, including women.[135] Although capacity laws have evolved to accept the presumption of capacity and to prioritize a functional approach to interventions, the stigma attached to the label of incapacity, and the real consequences that flow from it, continue to be highly contentious.

In its report on Vulnerable Adults and the Law, the Ireland Law Reform Commission (IRLC) has recommended using positive language, which promotes the recognition of capacity consistent with the CRPD and domestic human rights legislation.[136] Under this model, the IRLC’s proposed legislation would include a statutory definition of capacity as opposed to incapacity that encapsulates the cognitive approach. In practical terms, a person would be assessed as lacking capacity, rather than being found to be incapable.[137] Other jurisdictions, including Ontario, presume that all adults are capable and create positive qualifiers for personal appointments and negative disqualifiers to remove capacity after an assessment. Positive qualifiers do not result in a finding that an adult is incapable, even if a substitute decision-maker’s duties take immediate effect. The represented adult’s legal status of capacity is retained and he or she may, or may not, continue to make valid decisions, depending on the nature of the arrangement. Personal appointments are widely perceived as preferable to external appointments for these reasons and, also, because they allow the adult to proactively choose who they would like to assist them and in what way.[138]

The objective of some statutory personal appointments, such as enduring POAs, is to allow individuals to arrange for another person to manage their affairs in the event that they become incapable of doing so themselves.[139] Some statutes explicitly state that the capacity necessary to execute a personal appointment is lower than that which is necessary to manage one’s own property or personal affairs, and that an adult can make a personal appointment even after having been found incapable of the latter.[140] As with all methods to determine an adult’s capacity or incapacity, the specific criteria required to execute a personal appointment vary widely by issue-area and jurisdiction.

In recent years, alternative decision-making arrangements have received increased attention with the adoption of the CRPD, and law reform activity in Canada and abroad.[141] A range of personal appointments that do not require a finding of incapacity have been accepted as less restrictive options to attorneys and guardians for property. These are reviewed in Chapter V.

f. Alternatives to Capacity: Determining a Need for Assistance

One way that decision-making laws have incorporated the relational or social aspects of decision-making into determining capacity has been to restrict findings of incapacity to circumstances where the adult needs a guardian. In many jurisdictions, it is considered invasive and undesirable to introduce an adult into the guardianship system if his or her needs are met with assistance or if there is a less restrictive course of action available.[142] For example, courts may be prohibited from finding a person incapable until alternative decision-making arrangements have been exhausted.[143] These alternatives could include POAs or informal services, such as financial accounting or assisted living. A POA may also specify that it comes into effect on the fulfillment of a contingency other than incapacity,[144] such as missed rent payments or a purchase that is uncharacteristic of the adult. Ann Soden of the Centre for Law and Aging elaborates,

[T]here may be incapacity but no risk or need for formal legal representation, or there may be an easily-controlled risk which need not infringe on legal rights. Protective measures which are least restrictive of civil rights and autonomy may be as simple as making banking arrangements for bill payment, hiring an accountant or executing a banking or general power of attorney which names a trusted representative to handle one’s property and financial matters.[145]

Apart from decision-making laws, interventions are permitted in sectoral laws based on factors such as vulnerability and the need for assistance. Professor Margaret Hall claims that decision-making laws are in effect a response to vulnerability, albeit couched in the language of capacity, and that vulnerability could provide a more workable foundation for intervention while retaining an adult’s sense of personhood.[146] Vulnerability and the need for assistance have been used as a means to trigger the provision of programmatic health, social and other services that respond to systemic disadvantages associated with the circumstances of particular communities.[147] Relevant sectors include disability services, income supports and adult protection. In some sectors, these laws are considered to create positive entitlements for the special needs of a target client group, such as persons with developmental disabilities.[148] In others, they have been criticized as overly paternalistic, for instance where interventions are made to protect older adults from suspected self-neglect.[149] In this discussion paper, the LCO examines laws in the income support and social benefits sectors that create a process to establish a legal representative without requiring that an adult be found incapable, where there is a need to assist the adult in managing his or her funding (see Chapter V.B.5, Laws in the Income Support and Social Benefits Sectors).

4. Provincial Jurisdiction to Enact Capacity Laws that are Recognized for the Federal RDSP

The provinces regulate issues of capacity and legal representation for property management. The Constitution Act, 1867 does not enumerate capacity as an area of exclusive jurisdiction; it is subsumed under the provinces’ jurisdiction over “property and civil rights in the province” and “matters of a local or private nature”.[150] These powers, together with the responsibility for hospitals, “have been read by the courts as granting the provinces primary constitutional authority over matters of public and individual health”.[151] Mental health legislation exists in all of the provinces, and capacity and consent laws have been adopted in most.[152]

Some stakeholders have asked the federal government to amend the ITA permanently to address the subject matter of this project out of concern that, as a federal benefit, the RDSP should be treated uniformly across the country. They claim that the federal government has constitutional jurisdiction to regulate the issue of legal representation for the RDSP because it is essential to an effective, national legislative scheme.[153] Federal social benefits, such as the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Old Age Security (OAS) regulate payments to persons other than the recipient for reasons of incapacity. During the 2011 RDSP review, the federal government held extensive consultations with the provinces and territories to consider this proposal. However, the federal government has stated that it considers this issue to fall within provincial and territorial responsibility.

In the Economic Action Plan 2012, the federal government called upon the provinces and territories to examine whether a streamlined process to simplify access would be suitable for their jurisdictions. It recognized some provinces and territories as having instituted streamlined processes or other arrangements that could address the concerns of RDSP beneficiaries, including British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Yukon. The temporary federal rules under the ITA are intended to provide provinces and territories sufficient time to develop an appropriate, long-term solution.[154]

The federal and Ontario governments share the desire to improve access to the RDSP. The two jurisdictions have cooperated in the past in amending Ontario’s social benefit laws to create exemptions for the RDSP. The Ontario government has requested that the LCO review this matter with a view to making recommendations for reform. Therefore, although the LCO acknowledges the fact of stakeholders’ proposals, we consider our mandate to apply to Ontario laws, policies and practices and do not make recommendations specifically to the federal government. The LCO will review how other jurisdictions have dealt with the issue, but will adopt an approach that is consistent with Ontario’s needs and values. The LCO will also consider measures for the recognition of legal representatives across jurisdictions in Chapter VI.

| Previous | Next |

| First Page | Last Page |

| Table of Contents | |