A. Introduction

This Chapter reviews and critically analyzes laws in Ontario and other jurisdictions that provide insights into the development of an alternative process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries. The benchmarks for reform are used flexibly throughout the review and analysis (see Chapter I.C, Approaches to the Project Process). One step toward meeting the first of the benchmarks is to build on achievements that have already been made. With that in mind, this discussion paper focuses on key issues that were identified repeatedly in the LCO’s research and preliminary consultations.

The first key issue, the Choice of Arrangements to Establish a Legal Representative for RDSP Beneficiaries, is the core issue for this project. It considers the general arrangement to designate a legal representative or to have one appointed. The other key issues consider aspects of any choice of arrangement that merit in-depth analysis. These are reviewed in discrete sections on the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, the eligibility of legal representatives and safeguards against financial abuse.

Other issues were viewed as beyond the LCO’s mandate, not integral to the objectives for reform or overly resource-intensive. They include questions concerning the intricate procedural requirements that normally accompany personal appointments to validate them in law, and issues surrounding redress through the criminal and civil justice systems. Some of these issues will be reviewed in the LCO’s ongoing Legal Capacity, Decision-Making and Guardianship project.

B. Choice of Arrangements to Establish a Legal Representative for RDSP Beneficiaries

1. Introduction

This section considers existing arrangements to establish a legal representative for financial management in Canada and abroad, beginning with two Canadian provinces that have created a process specific to the RDSP. It continues to review other arrangements in decision-making laws, the law of trusts and laws in the income support and social benefit sectors. It concludes with a summary of several broad options for reform.

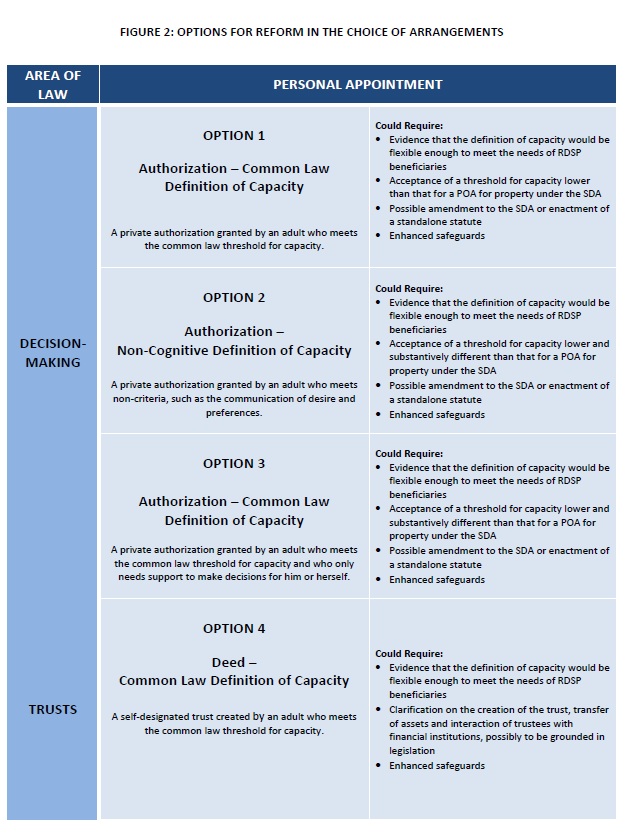

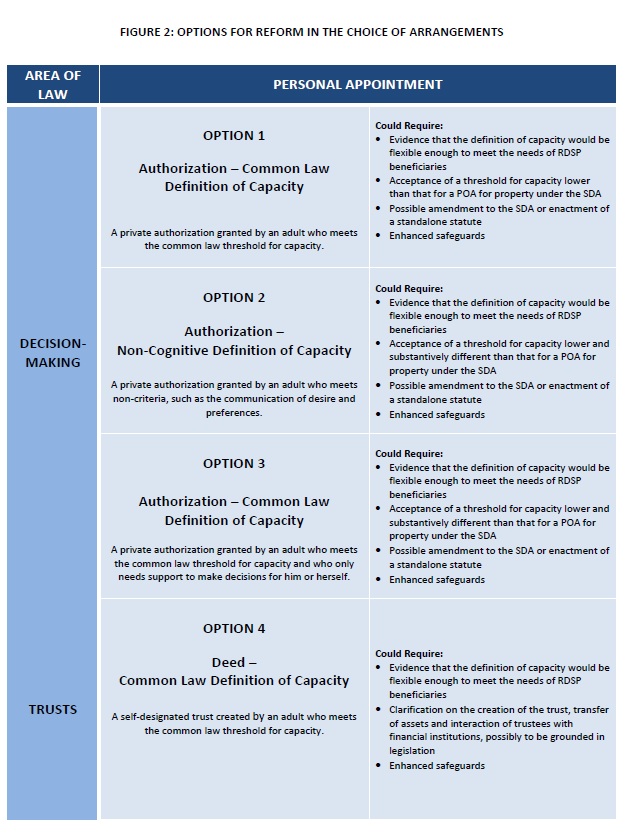

Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements, which is located at pages 90 to 91, provides a visual aid for readers considering the options for reform relating to the key issue reviewed in this section. The LCO invites you to access Figure 2 as a point of reference throughout the remainder of the discussion paper. The options for reform are discussed again in Chapter VI, Options for Reform, in terms of their relative implications for implementation along with a summary of the other key issues for the project.

Each of the existing arrangements reviewed in this section begins with the common law or statutory presumption of capacity. The establishment of a legal representative may then be contingent on an adult executing a personal appointment, on a finding of incapacity or on the determination that an adult needs assistance. For instance, personal appointments, such as POAs and self-designated trusts, are private arrangements that use positive language to define the level of capacity an adult must have to appoint another person for assistance with decision-making. Personal appointments do not result in a finding that an adult is incapable; however, there may be procedures in place to ensure that an appointment is legally valid, such as the presence of a witness. External appointments, including court and administrative tribunal orders, are public processes that may be based on an assessment of incapacity. It is, however, also quite common for laws to create a means to establish a legal representative without consideration of an adult’s capacity, for instance, where he or she has a confirmed need for assistance in managing daily expenses. These concepts and their potential implications for RDSP beneficiaries were discussed at length in Chapter II.B.3, What is Capacity? Foundational Concepts and Tensions.

There is a notable lack of empirical evidence on the practical implications and effectiveness of existing approaches. The LCO has commissioned a research paper in the Legal Capacity, Decision-Making and Guardianship project that will evaluate the implementation of some of these alternative arrangements.[278] We also hope to hear from the public in response to the issues raised here.

2. Canadian Provinces with a Process Specific to the RDSP

a. Saskatchewan Special Limited Powers of Attorney

The Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice and Attorney General has released an information booklet that recommends adults use a “special limited” POA to appoint an attorney for the RDSP.[279] The booklet was published prior to the federal RDSP Review and may not directly respond to the detailed challenges that stakeholders reported. Nevertheless, it deals with the overarching issue for this project inasmuch as it recognizes that “some persons with extreme mental disabilities do not have the capacity to enter into a contract. In this case, the person requires a legal representative appointed to sign the contract to set up an RDSP”.[280] Saskatchewan’s approach is creative and does not require legislative amendment. However, it is based on that province’s POA legislation, which contains a lower threshold for capacity than exists in Ontario.

In Saskatchewan, the threshold for capacity to execute a POA reflects the simplicity of the common law.[281] The Powers of Attorney Act reads, “[a]ny adult who has the capacity to understand the nature and effect of an enduring power of attorney may grant an enduring power of attorney”.[282] The explanatory booklet on the RDSP interprets this as a “low threshold” that could be met sufficiently “if a person understands that he or she is signing a paper that appoints a parent as attorney to create a savings account”.[283] A special limited POA for the RDSP that follows the booklet’s recommendation would have a similarly low requirement.[284]

The Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice and Attorney General suggests that a special limited POA be RDSP-specific only, limiting the scope of an attorney’s powers to that of a restricted plan holder, who would not have authority to decide terms for the timing and amount of one-time DAP withdrawals or the management of funds that have been paid out of the RDSP. It suggests that those extended powers would require full property guardianship due to concerns about safeguards against abuse:

It is suggested that the special limited power of attorney would give a parent the power to set up an RDSP, contribute funds, consent to someone else’s contributing funds, or transfer the RDSP to another financial institution, but not the power to withdraw funds or close the RDSP. For someone to have the ability to withdraw funds, he or she would have to apply for full property guardianship. Full guardianship has the protection of annual accountings, bonds and the ability for removal.[285]

The LCO has learned that restricting a plan holder’s authority to request one-time DAP withdrawals, as suggested in the Saskatchewan approach, could conflict with some financial institutions’ operational constraints. Under the ITA, a plan holder does not have authority to manage funds that have been paid out of the RDSP. However, plan holders can request that one-time DAP withdrawals be made from an RDSP on the beneficiary’s behalf prior to, or during, the receipt of mandatory lifetime payments that begin at age 60 (for more information see Chapter II.B).[286] The ITA enables each financial institution to stipulate as a term of contract whether DAPs are permitted.[287] This is one of the areas of flexibility conferred on financial institutions to account for variations in their operational constraints. Most, if not all, financial institutions permit DAPs as a standard term of contract. As a result, if a legal representative were restricted from requesting DAPs, he or she might not be able to agree to the terms of contract that are necessary to open an RDSP at many financial institutions. Adopting the Saskatchewan approach in Ontario could limit an RDSP beneficiary’s choice of service provider. It also appears not to be commercially viable for financial institutions to offer two types of contracts for the RDSP.

An additional possible shortcoming of Saskatchewan’s suggested approach is that it disentitles RDSP beneficiaries from making one-time withdrawals, unless they have the capacity to do so independently.[288] Therefore, it cannot serve those adults with diminished capacity who use the RDSP as a contingency plan throughout their lives, rather than for long-term savings. The LCO heard from one such person who regards the RDSP as a safety net in the event that his abilities, services or support networks change.[289]

Where an adult is unable to meet the capacity test for a special limited POA or needs a legal representative for withdrawals, the information booklet notes that Saskatchewan’s The Adult and Co-Decision-Making Act allows a person to apply to the Court of Queen’s Bench (the equivalent of Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice) to have a property guardian or co-decision-maker appointed.[290] Appointments can be for specific purposes and “any application could be limited to appointment as a guardian for the purpose of opening and managing the RDSP only, and not all of the adult’s property”.[291] In Ontario, the SDA stipulates that the court can “impose such other conditions on the appointment as the court considers appropriate”, which could also include the appointment of a guardian for RDSP decision-making.[292] However, RDSP beneficiaries and their families have experienced challenges with court-ordered guardianship, as discussed in Chapter III.C, Challenges Posed by Ontario’s Current Framework. Saskatchewan’s framework for co-decision making is reviewed as a less restrictive alternative to guardianship in Subsection 3(b), below.

Elements of the Saskatchewan special limited POA for the RDSP have been incorporated into Option 1 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements.

b. Newfoundland and Labrador Designation Agreements

Shortly after the federal government introduced measures in the Economic Action Plan 2012 to respond to feedback it received during the RDSP review, Newfoundland and Labrador passed a Bill to amend its Enduring Powers of Attorney Act to permit an adult to designate two authorized persons or the Public Trustee as his or her representative(s) for the RDSP under a “designation agreement”.[293] These amendments are not yet in force. As a result, the effectiveness of Newfoundland and Labrador’s response cannot be evaluated. The parameters of the legislation, and the parliamentary debates that led to its adoption, can be discussed in a general manner, as can related commentary from the legal community.

Designation agreements are intended to address the same challenges that RDSP beneficiaries and their families have faced in Ontario, including expense, complexity and the negative repercussions of substitute decision-making on an adult’s well-being.[294] The threshold for capacity to execute a designation agreement is a standard that is less restrictive than Newfoundland and Labrador’s requirements to execute a POA as well as those in Ontario with respect to property and personal care.[295] It has been described as “laudable in that it empowers persons with disabilities to appoint individuals they trust to administer their RDSPs without the expense and delay of applying to the court for a formal appointment of, in the Ontario context, a guardian of property”.[296]

Designation agreements are partially modeled on the British Columbia Representation Agreement Act,[297] which adopts a novel functional approach that emphasizes the expression of desire and preferences, and the existence of a relationship of trust with a legal representative.[298] The British Columbia legislation has been in force since 2001. Because there is more evidence of its effectiveness than the new Newfoundland and Labrador legislation, this approach is reviewed below under Subsection 3(a).

If an adult is unable to meet the threshold for a personal appointment, a spouse, cohabiting partner or child who has reached the age of majority can initiate an external appointment of the Public Trustee through the Trial Division Court (equivalent to Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice).[299]

In Newfoundland and Labrador, designates can be assigned powers beyond those of a plan holder to enable them to manage RDSP funds that have been paid out of the RDSP. Designates are bound to do so in accordance with set investments or expenses that a court has the power to order under the Mentally Disabled Persons’ Estates Act.[300] They also have the same responsibilities and standard of care to protect the adult’s best interests as an attorney.[301] These provisions circumscribe the designate’s powers and guard against financial mismanagement. However, concerns have been expressed that the Newfoundland and Labrador legislation is not adequately explicit about the scope of authority to engage in transactions with third parties when managing funds paid out of the RDSP. Vincent De Angelis has commented that

[w]hile the Act limits the scope of authority of a designate in dealing with the RDSP funds, it leaves more questions than answers. For example, does the Act authorize the designate who receives funds from an RDSP to: open a bank account or to hold the investments in his or her name; to contract for goods and services; or to buy property on behalf of the incapable person? These concerns have been expressed by some of the financial institutions who will be left to interpret the scope of authority of the designate.[302]

Furthermore, the LCO has heard from stakeholders that the safeguards in the Newfoundland and Labrador legislation place a higher degree of responsibility on the Public Trustee than may be implementable in Ontario due to resource constraints. Designates who are plan holders are required to submit an annual statement of accounts and operations to the Public Trustee, the adult and the issuing financial institution. Those who are authorized to receive payments from an RDSP must also submit a report summarizing all payments and expenditures. The Public Trustee is enabled to monitor designates and must also maintain a registry of designation agreements.[303] These and other considerations regarding safeguards against abuse are discussed more comprehensively in Section E below.

Elements of the Newfoundland and Labrador personal and external appointment processes have been incorporated into Options 2 and 5 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

6. Do you have experience with a special limited POA for the RDSP in Saskatchewan?

7. Are there lessons to be learned from provinces with a specific process to appoint a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries?

3. Decision-Making Laws: Alternatives to Ontario’s Framework

a. Personal Appointments

As noted previously, in recent years, alternative personal appointment processes have received increased attention with the adoption of the CRPD, and substantial law reform activity in Canada and abroad. A range of personal appointments that do not require a finding of incapacity have been accepted as less restrictive options to attorneys and guardians for property. They emphasize “the way in which most adults function in their everyday lives through interdependent decision-making which marshals available advice and support”.[304] Canada is internationally recognized as a leader in this regard and the discussion paper focuses on laws in a number of Canadian territories and provinces. Brief mention is also made of the Victorian Law Reform Commission’s (VLRC) endorsement of these arrangements.

Supported Decision-Making Arrangements

The Yukon and Alberta permit adults to execute personal appointments in order to formalize the role of informal supports that adults with diminished capacity habitually access to assist them. These are called supported decision-making agreements or authorizations, respectively. In the Yukon, supported decision-making arrangements are available for personal care and financial matters. In Alberta, they are available for personal care but not financial affairs. The Yukon’s Decision Making, Support and Protection to Adults Act[305] explains the purpose of supported decision-making agreements as

(a) to enable trusted friends and relatives to help adults who do not need guardianship and are substantially able to manage their affairs but whose ability to make or communicate decisions with respect to some or all of those affairs is impaired; and

(b) to give persons providing support to adults…legal status to be with the adult and participate in discussions with others when the adult is making decisions or attempting to obtain information.[306]

Government representatives in the Yukon and Alberta have indicated that the creation of these types of appointments was primarily a response to ideological concerns about definitions of capacity voiced in the disability community.[307] In Alberta, it also responded to a pragmatic need to formalize trusting relationships in the healthcare context in order to grant supporters access to confidential information.[308] Because agreements are not registered in either jurisdiction, their uptake is not known. The Office of the Public Guardian in Alberta has stated that they have been very popular.[309] In contrast, in the Yukon, it is believed that they have received limited use due, in part, to the lack of trusted or available supporters.[310]

It is important to note for the LCO’s project, that the scope of a supporter’s authority over financial decision-making is constrained. In both jurisdictions, a supporter is prohibited from making decisions on behalf of an adult, and a decision made or communicated with assistance is considered a decision of the adult.[311] An adult’s decision-making capacity is explicitly preserved.[312] In Alberta, an adult must have capacity to make his or her own decisions before receiving assistance. The process is recommended only for “capable individuals who face complex decisions, people whose first language is not English and people with mild disabilities”.[313] In the Yukon, “[t]hese agreements are for adults who can make their own decisions with some help”.[314] In its 2012 final report on Guardianship, the VLRC recommended that supported decision-making arrangements could be used where a person does not “clearly lack capacity but…would benefit from support” or “may have questionable capacity to make certain decisions without support, but who would clearly be able to do so with the support of a trusted family member or friend”.[315] Therefore, supported decision-making arrangements may not be suitable for adults who would continue to experience challenges in making decisions about the RDSP, despite receiving assistance.

Concerns have been expressed that “confusion and uncertainty could arise if support arrangements were available to assist people when making financial decisions”.[316] For these reasons, Alberta’s framework applies uniquely to personal care and cannot be used for financial management. The Office of the Public Trustee for Alberta informed the LCO that supported decision-making arrangements could cause confusion because financial transactions necessitate a clear seat of legal authority and, under these arrangements, the person with ultimate authority remains the adult whose capacity is at issue.[317] In the Yukon, a supporter can help an adult make decisions relating to banking, monthly budgeting, dietary expenses and other financial matters. However, the LCO heard from the Yukon Seniors’ Services and Adult Protection Unit that supported decision-making agreements are not used frequently in the banking context.[318]

Supported decision-making arrangements have also been characterized as giving rise to increased opportunities for abuse, including coercion and undue influence.[319] One area of apprehension is that “people dealing with such orders will mistakenly attribute decisional powers and responsibilities to people appointed as supporters, meaning that they operate as de facto guardianship orders without some of the checks and balances of true guardianship”.[320] Less formal arrangements are also associated with “less accountability”[321] and “being more distant from the oversight or purview of public sector bodies and agencies”.[322]

Although the VLRC recommended that supported decision-making agreements be used for financial matters, its recommendations would explicitly prohibit a supporter from communicating decisions about significant financial transactions to third parties, such as banks, government agencies, utility and other service providers, as a safeguard against abuse. The VLRC suggested, “these decisions will need to be communicated by the person themselves or other arrangements will need to be considered to assist them if this is not possible, such as, for example, substitute decision making”.[323]

Supported decision-making arrangements are summarized below under Option 3 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements.

Representation Agreements

Representation agreements (RAs) in the Yukon and British Columbia are another form of personal appointment but one that permits a “representative” to make legally enforceable decisions on an adult’s behalf with respect to the routine management of financial affairs. RAs are often characterized in the literature as facilitating supported decision-making[324] or as a less restrictive alternative to POAs and guardianship.[325] As was discussed above, Newfoundland and Labrador partially modeled its designation agreements—its response to the subject matter of this project—on British Columbia’s Representation Agreement Act.[326] During the federal RDSP Review, individuals and organizations submitted to the federal government that the British Columbia framework operates well to establish a legal representative for the RDSP.[327] The LCO heard proposals to create a comparable regime in Ontario during our preliminary consultations. The Representation Agreement Act is considered here after a review of its counterpart in the Yukon.

RAs in the Yukon sit at a midpoint between supported decision-making agreements and POAs. RAs give a representative authority to make decisions over prescribed financial matters, including signing negotiable instruments, taking steps to obtain benefits, investing and withdrawing funds, receiving and depositing pension or other money, and purchasing goods and services for day-to-day living.[328] The Regulations to the Adult Protection and Decision-Making Act that prescribe such areas for financial management do not explicitly list the RDSP.[329]

With a small population of just over 35,000 people, the Yukon has had approximately 30 agreements in place.[330] They have been used to apply for and manage funds on behalf of adults with diminished capacity who were eligible for the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement common experience payments (CEP).[331] In that context, they were intended as a protective measure for adults who could be vulnerable to financial abuse because their receipt of this funding would likely have been known to the community.[332] The example of the CEP raises concerns analogous to the RDSP, albeit the exigencies of applying for the CEP are not as complex as deciding RDSP terms.

The threshold for capacity to execute an RA in the Yukon is framed in the same manner as for supported decision-making agreements and POAs, requiring an adult understand the nature and effect of the agreement. Because RAs contemplate more complex transactions, the threshold is effectively higher than supported decision-making agreements. Depending on the powers that are awarded to the representative, it can be lower or potentially the same as for a POA. POAs are recognized more readily by banks and across jurisdictions. Therefore, where the purpose of an RA is the same as a POA, the Yukon Seniors’ Services and Adult Protection Unit promotes enduring POAs.[333]

Nonetheless, there are several distinctions between RAs and POAs. One major distinction is that RAs cannot grant plenary powers over financial management.[334] Additionally, RAs were designed to increase accessibility in terms of costs and validation requirements. Unlike in Ontario, in the Yukon, an adult’s lawyer must prepare a POA.[335] The costs of a lawyer’s services can be prohibitive for some adults and RAs circumvent that requirement. However, because a lawyer’s involvement is perceived as a safeguard against abuse, RAs are cushioned with several measures to mitigate the risks of abuse. The Yukon Seniors’ Services and Adult Protection Unit plays an enhanced role in witnessing RAs in screening and approving the suitability of representatives. Other safeguards that depart from Ontario’s regime include that RAs expire at the earlier of three years or when an adult’s capacity declines. Therefore, they “are not for adults who have a degenerative disease like Alzheimer’s” or for those whose decision-making abilities fluctuate.[336]

The LCO heard in our preliminary consultations that these provisions could possibly limit the applicability of the Yukon’s approach to the RDSP.[337] The RDSP is a long-term savings vehicle that involves many years of decision-making for a legal representative. Even if the scope of a legal representative’s authority is limited to that of a plan holder, he or she may need to approve one-time DAP withdrawals and monitor investments throughout the lifetime of the RDSP. If a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries were restricted to a few years, it would require an adult to execute a new agreement at regular intervals, or seek an external appointment should his or her capacity decline. This could be regarded as a positive safeguard or an added complication.

An RA in British Columbia can endure into an adult’s incapacity.[338] Similar to the Yukon, RAs in British Columbia include an extended list of areas for routine financial management. The Representation Agreement Act and related Regulations set out an exhaustive definition of what constitutes “routine financial management”.[339] Although RRSPs and Registered Retirement Income Funds (RRIFs) are listed as areas of activity, the RDSP is not listed. This is because the legislative framework pre-dates the availability of the RDSP. The LCO confirmed that some financial institutions have accepted RAs in British Columbia to establish a plan holder for RDSPs.[340]

The RDSP is a complex financial vehicle potentially involving substantial funds. It carries a risk of abuse that may be higher than the types of routine financial management currently covered under the law. Consequently, it raises significant policy concerns that the British Columbia government is considering.[341] The LCO heard that financial institutions desire clarity with respect to the application of the legislation to the RDSP, particularly regarding the withdrawal of funds and management of payments, where the risks of financial abuse are higher. This should be kept in mind in weighing the options for reform for this project.

The Representation Agreement Act came into force in 2001 after years of “unprecedented broad based community-government collaboration”.[342] With substantial input from the public about their aspirations for an alternative decision-making arrangement, it was positioned as one of several interlocking decision-making laws and was projected to supplant POAs. However, British Columbia’s POA legislation remained in force and, after a review of both regimes commissioned by the Attorney General, the two now operate in parallel.[343]

The Representation Agreement Act as it was first enacted permitted an adult to authorize his or her representative for financial affairs to “do, on the adult’s behalf, anything that can be done by an attorney acting under a power of attorney….”[344] In his Review of Representation Agreements and Enduring Powers of Attorney (McClean Report), A.J. McClean recommended that the wide scope of a representative’s authority be restricted to the routine management of the adult’s financial affairs and that enduring POAs persist as the chief instrument for property management.[345] In 2007, the Representation Agreement Act was modified to remove the option of authorizing a representative to make financial decisions beyond the routine management of an adult’s affairs. A representative’s powers now include such areas of decision-making as the payment of bills, receipt and deposit of pension income, and making investments, among others that are stipulated in the Regulations. The execution process was also streamlined, so that a lawyer is no longer required.[346]

RAs in British Columbia straddle supported and substitute decision-making. The Representation Agreement Act reads, “an adult may authorize his or her representative to help the adult make decisions, or to make decisions on behalf of the adult….”[347] While some interpret this as meaning an adult can choose either to ask for assistance or to have decisions made on his or her behalf, others say that this provision is meant to be interpreted as a holistic arrangement that captures the dynamics of the decision-making process: an adult may require more or less assistance depending on his or her abilities with respect to the decision at hand.[348] In his review, McClean noted that,

…at a philosophical, but in the end practical, level, it is said that the enduring power is too blunt a mechanism, vesting all decision-making power in the attorney. The representation agreement is more attuned to how decisions are made, and provides for not only joint-decision making and consultation, but also for taking into account the desires, beliefs and values of the adult.

Section 7 [representation agreement over financial affairs] was designed to provide a more flexible arrangement, under which a person could be assisted to make decisions, and have decisions made for him or her only as a last resort.[349]

The decision-making process that is mandated under the Representation Agreement Act is, thus, targeted at adults who may have fluctuating, diminishing and issue-specific capacity. The definition of capacity itself reflects this purpose in adopting a set of non-cognitive factors to be considered in determining whether an adult can execute an RA.[350] These factors create a threshold that is not just lower, but also substantively different, from that for a POA. In particular, it reflects a social policy decision to extend personal appointments to adults with significant mental disabilities who may have “unique ways of communicating” that can be understood by a trusted person who has personal knowledge of “what he or she values and wants and what he or she dislikes or rejects”.[351] The factors are the following:

a) whether the adult communicates a desire to have a representative make, help make, or stop making decisions;

b) whether the adult demonstrates choices and preferences and can express feelings of approval or disapproval of others;

c) whether the adult is aware that making the representation agreement or changing or revoking any of the provisions means that the representative may make, or stop making, decisions or choices that affect the adult;

d) whether the adult has a relationship with the representative that is characterized by trust.[352]

Framing capacity in this manner has been favoured in the disability community as a means to recognize the “shades of grey with respect to capacity”.[353] A study conducted by the Nidus Personal Planning Resource Centre and Registry, a voluntary registration and advocacy support service, found that 989 RAs were made and registered between 2006 and 2009, 70 per cent of which included authority over financial affairs. The majority of adults executing RAs were between the ages of 19 and 29, followed by those between 80 and 89, but people of all ages have accessed these arrangements.[354] The LCO also heard during our preliminary consultations that RAs have been recommended as a tool to assist adults in managing government income supports and social benefits in the developmental disability sector.[355]

However, legal practitioners have been hesitant to embrace representation agreements. RAs originally required a lawyer’s validation and the discrepancy between the statutory threshold for capacity and the common law capacity to instruct counsel has been a source of unease. Despite eliminating a lawyer’s participation in the process of validating an RA, this tension has not been resolved for adults wishing to access legal advice.[356]

Concerns have also been raised about whether there is an increased potential for abuse under RAs because of the liberal test for capacity. The LCO heard from certain stakeholders that the cognitive approach to determining capacity should not be altered in the context of complex financial transactions, such as the RDSP, where the risk and consequences of abuse are high. In its review of the Victorian guardianship regime, the VLRC declined to adopt the British Columbia approach, recommending instead an external appointment process for adults whose diminished capacity does not meet the traditional cognitive test.[357] Furthermore, the flexibility in the scope of a representative’s authority, which includes assisting an adult and making decisions on his or her behalf has led some to doubt if there are adequate safeguards to protect an adult’s participation.[358]

The Representation Agreement Act does contain enhanced safeguards against financial abuse and the misuse of a representative’s powers. The safeguard that differs most notably from arrangements in other jurisdictions is the requirement that an adult appoint a monitor in certain circumstances.[359] An adult is not required to appoint a monitor if he or she has at least two representatives who must act unanimously in exercising their powers. If an adult has only one representative who is a spouse, the Public Guardian and Trustee, a trust company or credit union, a monitor is also not compulsory.[360] In its study, Nidus found that even where monitors are not required, adults do appoint them. Overall, 52 per cent of RAs included a monitor and 74 per cent of adults chose to appoint a monitor rather than name more than one representative to act jointly. The majority of monitors are extended family members,[361] friends and siblings. Approximately 20 per cent of RAs include two representatives acting jointly. Few RAs are constituted otherwise.[362]

The Public Guardian and Trustee for British Columbia has confirmed that they have responded to complaints regarding RAs but has also suggested that they are not prevalent.[363] There has not been a “significant case taken to court regarding financial exploitation by a representative” as had “been anticipated by some legal professionals”.[364] Nevertheless, as noted previously, the risks of abuse may be higher with the RDSP than matters of routine financial management because of the wealth the RDSP attracts and the complexity of decision-making. This could be a particular concern should the scope of a legal representative’s authority extend to requesting withdrawals and managing funds that have been dispersed.

Elements of the Yukon and British Columbia’s representation agreements have been incorporated into Options 1 and 2, respectively, in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

8. Would it be appropriate to lower Ontario’s threshold for capacity to grant a POA for property management for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries?

9. If a different threshold for capacity to execute a personal authorization for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries were accepted in Ontario, what definition of capacity would be flexible enough to meet the needs of RDSP beneficiaries?

10. Would a threshold for capacity based on the common law standard or non-cognitive criteria increase an RDSP beneficiary’s risk of vulnerability to financial abuse and misuse of a legal representative’s powers?

11. How would a supported decision-making arrangement or representation agreement for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries impact third parties?

12. How could a personal appointment process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries be implemented in the Ontario context? Would it require an amendment to the SDA or the enactment of a standalone statute?

b. Streamlined Court and Administrative Tribunal Appointments

External appointments generally apply to circumstances where an adult does not have a private arrangement, such as a POA, and the adult’s challenges with decision-making are such that he or she cannot meet the threshold of capacity required for a personal appointment. An adult or another person may initiate an external appointment where it is believed that the adult experiences diminished capacity and is in need of assistance. Additionally, external appointments can be used as the first avenue of recourse for arrangements where the oversight of an independent adjudicator is desirable. Court orders for co-decision making are an example. In this section, co-decision making is considered as an alternative decision-making arrangement followed by a review of streamlined court applications and administrative tribunal proceedings.

Co-Decision Making

Alberta and Saskatchewan permit an interested party to request that a judge appoint a co-decision maker to make decisions jointly with an adult with diminished capacity. In Saskatchewan, co-decision making is available for personal care and financial matters. In Alberta, it is available for personal care but not financial affairs. In Saskatchewan, a judge may appoint a co-decision maker as a less restrictive alternative to guardianship, where his or her “capacity is impaired to the extent that the adult requires assistance in decision-making in order to make reasonable decisions…and is in need of a property co-decision maker”.[365] In both jurisdictions, co-decision-making arrangements are intended for adults who can make decisions for themselves with assistance.[366]

Although a co-decision making appointment is established through the courts, it strongly resembles the supported decision-making arrangements discussed above.[367] Co-decision making differs from supported decision-making insofar as a co-decision maker shares legal authority to make decisions with the adult. However, he or she must “acquiesce in a decision made by the adult and shall not refuse to sign a document…if a reasonable person could have made the decision in question and no loss to the adult’s estate is likely to result from the decision”.[368] A co-decision maker’s authority may, therefore, simply consist of advising the adult and giving effect to his or her decision.

In contrast to supported decision-making, co-decision making does also have an added degree of formality for third party service providers. A co-decision maker can sign a contract in the banking context and a contract signed by either person alone may be voidable.[369] Joint signatory arrangements, such as bank accounts, have been used in financial institutions for quite some time. Therefore, according to the VLRC, while it may take time for third parties to become accustomed to co-decision making arrangements, they should “not cause significant legal and commercial problems”.[370] Others perceive the impact of co-decision making on third parties differently. In Alberta, co-decision making does not apply to financial management because it could cause confusion and uncertainty.[371] In their review of alternative decision-making arrangements in Canada and abroad, Terry Carney and Fleur Beaupert remark,

Redolent of the fine distinctions between ownership rights under joint tenancies and tenancies in common (whether co-owners do or do not acquire a ‘share’), these options are among the most problematic in terms of public understanding of their social and legal function: they risk failing to pass the ‘corner shopkeeper’s understanding’ test.[372]

Co-decision making only occurs as an external appointment, which in Saskatchewan entails a court proceeding. The VLRC cited two reasons for its belief that it would be inadvisable to establish a co-decision maker through a personal appointment. These include the acknowledgement that the adult will have impaired capacity, which calls into question the ability to “make a sound choice to enter into a co-decision making arrangement and to appoint a responsible person”.[373] Additionally, the VLRC found that “co-decision making appointments are not an ideal future planning mechanism”.[374]

Co-decision making accepts that an adult’s capacity may change over time and seeks to assist only with needs that are identified at the time of the appointment. At the time of an appointment, the adult might have difficulty making decisions alone but must be able to make them with the assistance of another. As an external arbiter, the court’s role is to provide independent scrutiny and a mechanism for ongoing review. If an adult’s capacity diminishes further, an order for co-decision making may be terminated.[375]

In a recent study on guardianship reform in Saskatchewan, Professor Doug Surtees surmises that concerns about future planning may explain the low usage of co-decision making arrangements to date. Professor Surtees reviewed nearly all court applications over a seven-year period after Saskatchewan’s co-decision making legislation came into effect. He found that an overwhelming number of orders continue to grant virtually plenary guardianship and only 30 out of 446 orders were for co-decision making. Interviews conducted with lawyers involved in the applications indicate that 52 per cent agreed that powers beyond those needed as of the date of the application should be requested where there is a “reasonable likelihood” that an adult will require additional assistance at a later date, “as this will reduce the need for further applications”.[376] Another 38 per cent agreed that supplementary powers should be requested where there is a “possibility” they will be needed in the future.[377]

If the uptake of co-decision making has indeed suffered out of the concern that an adult’s capacity will decline in future, it is unfortunate. It would be inconsistent with the principle of least restriction that is fundamental to Saskatchewan’s legislation.[378] However, it does highlight for the purposes of the LCO’s project on the RDSP that, like supported decision-making agreements, co-decision making is primarily aimed at adults who are able to make decisions with assistance; it may not be suitable for some adults with fluctuating or degenerative conditions. A second plausible explanation that Professor Surtees tenders for the low usage of co-decision making in Saskatchewan “is that the orders that are granted, despite their tendency to be virtually all plenary orders are, in fact, the orders that are needed”.[379]

Saskatchewan’s co-decision making appointments are included below under Options 5 and 6, in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements, which summarize streamlined court processes and administrative tribunal hearings, respectively.

Streamlined Court Applications

The procedural exigencies of court appointments have been associated with increased complexity and legal costs that could be prohibitive for RDSP beneficiaries seeking a legal representative. In Ontario, the SDA allows for the summary disposition of guardianship applications. Summary disposition applications are made by filing required documents with the court for a judge’s consideration. They circumvent the default requirement of participating in a hearing and may reduce costs associated with legal services. In other jurisdictions, such as Alberta and Saskatchewan, desk applications that do not require a hearing are also available for substitute and co-decision-making arrangements, which are a less restrictive alternative to guardianship. In Saskatchewan, desk applications for co-decision making are available for personal care and financial matters, while in Alberta they are restricted to personal care.

There is little evidence of how summary dispositions operate in Ontario. The LCO’s preliminary consultations confirm that summary disposition applications are used. The LCO heard from one lawyer that in some cases summary disposition applications have worked effectively and expediently as a streamlined process. They minimize the possibility of a court appearance, which makes them more cost-effective. They have particularly worked well in the developmental disability community, when the relationship between the adult and his or her family members is “straightforward” and the application is not contested.[380]

However, summary disposition applications are not used frequently. The LCO has heard that one explanation for the low usage of summary disposition applications in Ontario is that appointing a guardian without a hearing has raised concerns regarding due process.[381] The SDA does contain measures to ensure an adult’s rights of due process. For instance, it requires that notice of the application be served with accompanying documents on the adult alleged to be incapable, specified family members and the OPGT, among others.[382] The SDA also requires at least one statement of opinion by a capacity assessor that an adult is incapable and, as a result, the same measures of due process that apply to capacity assessments for statutory guardianship appointments also apply to those for summary disposition applications. These include that a capacity assessor must provide information to the adult about the purpose and effect of the assessment and that the adult is entitled to refuse the assessment.[383] In spite of these measures, it appears that the perception that summary disposition applications do not sufficiently safeguard an adult’s rights of due process persists. The Law Society of Upper Canada states the “it should be noted that not all jurisdictions or members of the bench allow guardianship matters to proceed in this fashion, citing that the seriousness of the relief requested requires a hearing”.[384]

Concerns regarding due process in the context of streamlined court applications have been noted in other jurisdictions. For instance, Professor Doug Surtees informed the LCO that in Saskatchewan, the majority of court orders are made through an application without a hearing. Although this procedure was designed to be accessible, he believes it does not consistently safeguard an adult’s rights. Professor Surtees reports that the process is difficult to navigate, the adults who are the subjects of an application are infrequently consulted with respect to their wishes and they may not be thoroughly apprised of the process.[385]

Alberta’s desk applications for guardianship and co-decision making provide an example of a streamlined court process with enhanced oversight and support from a government agency. In Alberta, a self-help kit has been made available to members of the public with forms that have been designed to be user-friendly.[386] Applicants forward the desk application documents to specialized review officers within the Office of the Public Guardian who ensure proper completion of the documents and fulfill other duties including providing notice of the application to appropriate parties, drafting a review officer’s report and forwarding the documents to the court. The review officers typically meet with the adult who is subject of the application to consult with them about their wishes. The LCO heard that in Alberta, desk applications have generally been regarded as a success in terms of the number of persons using the process and reducing the need for a lawyer.[387]

Another shortcoming of summary dispositions in Ontario was identified as cost. While legal costs may be reduced because they do not require a hearing, the costs of summary disposition applications can range between approximately $7,500 and $10,000 in urban centres. Documentation from capacity assessors makes up a large portion of these costs, possibly $3,000 to $4,000.[388] Additionally, if a judge is not satisfied that a proposed appointment is appropriate based on evidence in the application, he or she may order further information or a hearing.[389]

Should an alternative process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries proceed through a streamlined court application, such as summary disposition, these expenses would need to be addressed. Every RDSP beneficiary must undergo an assessment to determine his or her eligibility for the DTC. Qualified medical professionals conducting those assessments embody an axis point that all beneficiaries pass through at some point in time before applying for the RDSP. The LCO received suggestions that these qualified medical professionals could create a resourceful and less costly means of determining an adult’s capacity.[390] With adequate support and direction, they could also possibly assist in appraising an adult’s need for a legal representative, in addition to, or in lieu of a finding of incapacity.

Furthermore, any possible streamlined court application for RDSP beneficiaries in Ontario would need to respect an adult’s rights to due process, including consultation with respect to his or her wishes. The involvement of government staff could better secure rights of due process and increase uptake. Their involvement would, however, require additional resources that the Government of Ontario may not have. It is worth considering whether non-governmental organizations might play a role to minimize stress on government resources. Nevertheless, appropriate guidance and logistical support from the Government of Ontario would be necessary for a streamlined court process to operate smoothly.

The option of a streamlined court process is summarized below under Option 5 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements.

Administrative Tribunal Proceedings

Administrative tribunals with authority to appoint a legal representative for adults with diminished capacity exist in several jurisdictions. Speaking of such a tribunal in its jurisdiction, the Queensland Law Reform Commission explains that it was intended to provide

an accessible, affordable and simple, but sufficiently flexible way of establishing whether a person has decision-making capacity and of determining issues surrounding the appointment and powers of decision-makers where it is necessary for another person to have legal authority to make decisions for a person whose decision-making capacity is impaired.[391]

The Consent and Capacity Board is Ontario’s administrative tribunal with expertise in issues of capacity and decision-making. Chapter IV reviewed the CCB’s mandate to create, amend and terminate substitute decision-making arrangements for incapable adults in area of health care. Insofar as this chapter considers alternatives to Ontario’s current framework, it is important to note that administrative tribunals in other jurisdictions also appoint substitute decision-makers for property management.[392] Manitoba’s process to establish a substitute decision-maker for persons with developmental disabilities under The Vulnerable Persons with a Mental Disability Act is a notable example of an administrative proceeding that involves a hearing panel process in another Canadian province.[393] The VLRC has also recommended that the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal extend its mandate to making appointments for supported and co-decision making for financial affairs.[394]

The LCO received suggestions from select stakeholders that the CCB’s mandate might be extended as an option for reform. If an external appointment process is desirable, the CCB could play a role as an impartial arbiter that is more accessible than the courts. As noted above, the CCB currently faces serious resource constraints. In the 2012/13 fiscal year the Board received 6,000 applications and scheduled over 3,100 hearings all while adhering to the Board’s legal obligation to schedule hearings within 7 days of receipt. The current staff complement can only handle the existing caseload and will face considerable challenges with any significant increase in volume. According to the Board’s annual reports the CCB is running a deficit of approximately $1 million per year. The Board’s current resource constraints must be a factor if considering adding to its mandate.[395]

Beyond resource constraints, the CCB advised the LCO that it would be challenging to reconcile an alternative process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries with its mandate and ongoing operations. The CCB determines if an adult is capable or incapable as a matter of law under the SDA and Health Care Consent Act, 1996[396] based on evidence presented to it from qualified medical practitioners and capacity assessors. The application of a different standard for capacity for an issue-specific area of decision-making, such as the RDSP, would not be a natural fit with the CCB’s current mandate. It would require training and, possibly, reconstituting the CCB membership to better reflect the RDSP context, for instance, through the addition of financial experts.[397] Any change in its operations would need to follow a direction from the province bolstered by appropriate resources. Given that resource constraints exist at all levels in Ontario, it is not clear whether this is feasible.

The possibility of extending the CCB’s mandate is summarized below under Option 6 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

13. Would a co-decision making arrangement be flexible enough to meet the needs of RDSP beneficiaries?

14. How would a co-decision making arrangement for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries impact third parties?

15. Could a streamlined court process be used for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries as an “alternative course of action” to guardianship? Would an amendment to the SDA or enactment of a standalone statute be necessary to expand the Superior Court of Justice’s mandate?

16. What measures would be required to make a streamlined court process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries fair, cost-effective, speedy and user friendly?

17. Is there a role for community organizations in providing enhanced support at the front-end of a streamlined court process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries?

18. Would it be feasible to integrate a process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries into the existing mandate of the Consent and Capacity Board?

19. Should an external appointment process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries be based on an assessment of capacity or an adult’s need for assistance in RDSP decision-making?

4. The Law of Trusts

a. Introduction

Before the introduction of the RDSP, private financial planning for persons with disabilities focused on the law of trusts.[398] Trusts are regulated by the common law and by statute. The RDSP is itself a statutory trust: the ITA stipulates that RDSP funds are to be held in trust by a financial institution, which acts as the trustee.[399] Trusts are a well-established method of assisting persons with disabilities in managing their assets, such as life insurance, inheritances and personal injury settlements.

There have been many comparisons of the advantages of the RDSP and traditional trust mechanisms, and lawyers may advise their clients to set up both, depending on their means and interests.[400] However, the interaction of RDSP funds and trusts has not been addressed. Several stakeholders in the LCO’s preliminary consultations suggested that a trust could respond appropriately to the challenges of RDSP beneficiaries by permitting a trustee to act as a legal representative.

The law of trusts is very complex and whether a trustee could act as a legal representative for the RDSP is uncertain. Funds in an RDSP may include mixed contributions from public and private sources, and it is unclear who would have legal authority to create a trust for an RDSP beneficiary and to transfer these funds to the trustee. As a result, clarification on the creation of a trust, the legal authority to transfer RDSP funds and the interaction of trustees with financial institutions would require strong guidance from the province.

This section reviews a number of trusts that are available in Canada and abroad to consider whether a trust mechanism could be used as part of the process for establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries.

b. Establishing a Trust for Adults with Diminished Capacity

Trusts differ considerably according to the type of trust and each trust’s conditions, which are particularized in the legal instrument that creates it, variously called, among other things, the deed, agreement or declaration. In addition, the law of trusts is constantly evolving over time.[401] This flexibility is valued as a positive characteristic because trusts are adaptable to social needs; however, commentators have remarked that it makes a strict definition problematic. That said, trusts do have several essentials features. One of their essential features is a fiduciary relationship between the trustee and beneficiary. This makes them different from a simple contract and the courts can impose a trust where a relationship warrants it, even in the absence of an express agreement. Another feature is the transfer of a person’s property to the trustees who administer it for his or her benefit.[402] Eileen E. Gillese provides a useful description of these features:

In its simplest terms, a trust arises whenever there is a split in legal and beneficial ownership to property – that is, whenever one person holds legal title to property and is legally obliged to manage that property for the benefit of another.[403]

A trustee is a fiduciary who holds, and makes decisions about, property for the benefit of the beneficiary.[404] A substitute decision-maker under the SDA is also a fiduciary who must manage an adult’s property for his or her benefit.[405] Under decision-making laws, a trust company can be appointed as a substitute decision-maker or representative.[406] Moreover, trusts that are established by private individuals are regularly used in “innovative and imaginative” ways to “provide for the financial interests of an incapable adult”.[407] Estates and trusts lawyer Harry Beatty explains,

Where there are significant limitations on the ability of a beneficiary to manage money or property, a trust is a means of ensuring that they will be managed prudently.

Where the impact of the disability is episodic, as may occur for example with multiple sclerosis or bipolar disorder…the trust will assist the beneficiary during the most difficult periods in her or his life, when the beneficiary may be temporarily unable to deal with financial issues, or finds it very difficult to do so.[408]

A trust can be used as a future planning mechanism, like a POA, that a capable adult establishes for him or herself in anticipation of declining capacity.[409] The test for capacity to create a trust is not unlike that for a common law POA. It is less stringent than the threshold for capacity to grant an enduring POA in Ontario under the SDA, requiring only that the adult is able to “understand substantially the nature and effect of the transaction”.[410] As noted previously, this threshold may be too high for some adults with mental disabilities depending on the scope of a legal representative’s authority. The same observations regarding Saskatchewan’s special limited POAs and the Yukon’s representation agreements can be made with respect to self-designated trusts because they adopt a similar definition of capacity (see Sections 2 and 3, above).

Self-designated trusts are considered under Option 4 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choices of Arrangements.

c. Types of Trusts: Discretionary and Henson, Court-Ordered and User Controlled

A trust can also be established by an individual other than the beneficiary or through the courts. There are many types of trusts and this discussion paper cannot review all of them. Three types of trusts that are commonly used in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom for persons with disabilities are reviewed below.

Discretionary and Henson Trusts

Discretionary trusts are usually created by one or more relatives of a family member with a mental or physical disability. When used for disability benefits planning purposes, they are referred to as Henson trusts.[411] The trustees who administer a Henson trust have discretion in determining who the beneficiaries are, and authorizing contributions, investments and withdrawals. This makes the role of trustees somewhat analogous to that of a plan holder for the RDSP. The trust terms may provide that payments be made to or for the benefit of the beneficiary. For instance, trustees can direct payments to the beneficiary through a separate bank account in appropriate amounts to give him or her control over day-to-day spending. Payments can also be made directly to individuals and organizations for the benefit of the beneficiary, such as a landlord, a utilities company or a provider of disability services.

Henson trusts are not considered assets under ODSP. Payments from a Henson trust may also be exempt as income under ODSP within specified limits.[412] The treatment of Henson trusts under provincial income support programs, such as ODSP, can be advantageous to many persons with disabilities who rely on government income supports. However, the absolute nature of the discretionary powers of trustees is inconsistent with the RDSP policy objectives, goals for reform and principles for the law as it concerns persons with disabilities, including dignity, participation and autonomy. It also increases the risks of financial abuse.

Several commentators have noted that Henson trusts are particularly prone to conflicts of interest because “[i]f a trustee is also a residual beneficiary, for example, it is relatively easy for the trustee to preserve the trust fund by denying requests for discretionary expenditures on the person with a disability”.[413] These risks related to withholding funds are mitigated in the case of the RDSP, which was purposefully designed to be paid out regularly in set amounts to beneficiaries after the age of 60. Nonetheless, RDSP beneficiaries would have few rights of recourse to challenge a legal representative’s decision with respect to any type of financial management under an arrangement like a Henson trust.

Beyond Henson trusts, Ontario does recognize trusts that allow the beneficiary to participate in decisions regarding the funds in trust. Conditions can also be placed on the trustees’ authority in the trust deed, for example, regarding investments or expenditures. The remainder of the discussion in this section concerns these types of trusts.

Court Ordered Trusts

The Superior Court of Justice has inherent and statutory jurisdiction over trusts. The Court can impose a common law trust where there is a fiduciary relationship that demands the recognition of a trust, even though the parties did not expressly create one. The Court’s authority over these so-called “constructive” trusts is largely limited to a remedy to compensate persons for losses that result from a relationship of unjust enrichment.[414] The Court also has jurisdiction to determine matters concerning the administration of trusts inherently, and under the Trustee Act and Rules of Civil Procedure.[415] For instance, it can appoint trustees, fix their compensation and preside over an accounting of the trust’s administration.[416]

A judge can create a trust and order that assets be transferred into trust following a court proceeding to safeguard the assets of a successful litigant. For instance, in Ontario, the courts have authority to deal with awards of support to dependents by ordering that they be held or paid in a trust under the Succession Law Reform Act. Where any property is held in trust arising from a will, settlement or other disposition, the Variation of Trusts Act also permits the Superior Court of Justice to approve any arrangement varying the trust or enlarging the powers of the trustees on behalf of a person who is incapable of assenting.[417] In the United States, courts have jurisdiction under the United States Code to create a “special needs trust” for a person with a disability to protect his or her assets from being counted as income and resources for the purposes of Medicaid eligibility. Funds may provide an income stream to the beneficiary or be paid to third parties for goods and services.[418]

In both Canada and the United States, standard safeguards against abuse that can be incorporated into a trust instrument include the appointment of more than one trustee or of a trust protector. A trust protector is a third party who is enabled to exercise independent oversight over the administration of the trust and monitor the performance of the trustee(s). The trust instrument can define the powers of a trust protector, which can resemble those of a monitor under a British Columbia representation agreement.[419]

If a court-ordered trust mechanism is desirable as an option for reform, the procedural exigencies involved in the application process must be fair and accessible. Subsection 3(b), above, addresses streamlined court and administrative tribunal appointments and many of the observations made there are also relevant to this option.

The external establishment of a trust under the supervision of the courts is considered under Option 7 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choices of Arrangements.

User Controlled Trusts

User controlled trusts are an example of a type of trust that is regularly accessed to manage government benefits. In the United Kingdom, the English national Department of Health and local government authorities recommend that recipients of direct payments for government social services, who are unable to manage their finances, get support from a user controlled trust.[420] Since 1996, persons eligible for government benefits for social care, including adults with mental disabilities and older adults, have been able to receive direct payments for services according to individualized budgets. The policy framework for direct payments is national but local government authorities administer them to their constituencies.

Soon after direct payments began, concerns were expressed that certain groups would face challenges in accessing them. The Department of Health’s annual returns revealed low uptake among older adults, and persons with developmental and psychosocial disabilities. Research into the low uptake rates indicates that one of the factors was that recipients required support with managing direct payments. User controlled trusts were promoted to address this problem, among other strategies.[421] The National Health Service describes user controlled trusts as “a way for people who don’t have capacity or ability to manage their own direct payments to get support from people close to them”.[422]

A user controlled trust can be established by three or more trustees “drawn from family members, and wider contacts such as friends and neighbours, or people who have worked with the direct payment recipient and know them well”.[423] Once the trust instruments are executed, the trustees must enter into a contract with the government service provider and open a separate bank account for payments. Depending on the conditions set out in the trust, the user controlled trust can be responsible for managing the beneficiary’s budget, employing professional service providers and making purchases.[424]

The beneficiary is the controlling decision-maker of a user-controlled trust and his or her expression of preferences is intended to be the basis for the trustees’ decisions, despite issues of capacity.[425] The Department of Health states that “as the person getting the support/services, [the individual] should be central in any planning meetings, and their wishes always consulted”.[426] Several government sources recognize that an adult’s behavior and communications are sufficient indicators of choice, and that user controlled trusts are suitable for persons with fluctuating abilities. The Kent County Council states,

An Independent Living Trust is not the same as one which promotes substitute decision-making. It is a tool to enable people to maintain independent living, choice and control – the individual directs the decisions that such a Trust makes and becomes involved as much as possible in the process e.g. attending trust meeting[s].

A Trust is often used where people make choices and indicate preference through things such as body movement, gestures, vocalization, behavior and emotions. A Trust may also be set up for people who have progressive impairments and may, one day, be less able to manage their support without a Trust e.g. someone with dementia or extended ‘crises’ periods of mental ill health.[427]

One way in which user controlled trusts differ from other private trusts is in the level of support that is made available to the trustees through local government agencies that approve them. This makes user controlled trusts similar to the arrangements discussed in the section below on laws in the income support and social benefits sectors. In addition, it could lower the expense that is normally associated with setting up a trust privately by retaining a lawyer. As is also discussed below in the same section below, this intense participation of government agencies requires resources that the Government of Ontario may not have at present. Nevertheless, user controlled trusts can incorporate safeguards that are regularly drafted into trusts governance documents, such as holding periodic meetings, reporting and accounting among co-trustees.

There is some empirical evidence on the efficacy of user controlled trusts. Commentators have made positive remarks about how they have increased the uptake of direct payments in the community of persons with learning disabilities.[428] One study that surveyed the implementation of strategies to increase uptake of direct payments in the United Kingdom noted drawbacks, such as the feeling that the beneficiaries’ abilities to contribute to decision-making were not always fostered as much as possible.[429] However, it contained an overall positive assessment:

[User controlled trusts] were seen as having the advantages of sharing responsibility, coordinating support to an individual, and giving trust members a clear role where they take their responsibilities seriously. Enabling an individual to have choice and control, even though not passing the ‘able and willing test’ was given as one of the advantages.

The schemes were seen as hugely beneficial to users, since in many cases they would have been refused a direct payment without them….[430]

The approval of a trust under the supervision of a government agency is considered under Option 8 in Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choices of Arrangements.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

20. Could a trustee act as a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries in Ontario?

21. Who would have legal authority to create the trust for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries and to transfer the RDSP funds to the trustee?

22. What measures would be required to implement a trust mechanism as an option for reform in Ontario?

23. Would a self-designated trust based on the common law threshold for capacity be flexible enough to meet the needs of RDSP beneficiaries?

24. Could a streamlined court process to appoint a trustee as a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries be integrated into the Superior Court of Justice’s existing jurisdiction over trusts?

25. Could an Ontario government agency be charged with approving a deed of trust for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries? If so, which government agency would be suitable?

5. Laws in the Income Support and Social Benefits Sectors

a. Introduction

This Chapter reviews processes that are embedded into income support or social benefits programs in order to appoint a person to manage a recipient’s funding as a less restrictive option to guardianship. Income supports and social benefits take different forms across jurisdictions. The RDSP is a unique financial investment vehicle. Much more common are government programs that cover basic living expenses, such as ODSP, and that provide individualized funding based on the recipient’s special needs, for instance, direct funding for persons with development disabilities under the Ministry of Community and Social Services Act. These forms of income supports and social benefits are discussed throughout this discussion paper, particularly in Chapters II.A and IV.A, and directly above in Section 4 on user controlled trusts.

Where income supports and social benefits are distributed as direct payments to an adult, he or she may experience difficulties in planning and managing the funds. An adult may proactively request assistance from his or her case worker. Alternatively, the adult’s case worker or a third party, such as a parent or spouse, may initiate the appointment of another person to manage the adult’s payments. The appointment process in these situations depends on rules in the relevant program. Programs can be national or subnational, or specific to a target client group. This chapter reviews select programs in Canada and abroad, making reference to what little empirical evidence there is to evaluate them.

b. Income Support Programs

Ontario Disability Support Program

Approximately 50,000 ODSP recipients obtain assistance from what is commonly referred to as an “ODSP trustee” to manage their income support payments.[431] The Ontario Disability Support Program Act, 1997 (ODSPA) empowers the Director to appoint such a person to act for a recipient if there is no guardian of property or trustee and the Director is satisfied that the recipient “is using or is likely to use his or her income support in a way that is not for the benefit of [the recipient and his or her dependents]”.[432] The roles and responsibilities of a trustee are described in the ODSP Regulations and Income Support Directives (Directives).[433] Together, they provide guidance on issues including how the process is triggered, factors to be taken into consideration in appointing a person to act for the recipient and accountability measures.

Those appointed under the ODSPA are not formal trustees, such as those discussed in Section 4 above, and their authority is not recognized to decide matters for the RDSP or by the CRA for income tax purposes.[434] The appointment process can be initiated at the request of the recipient, his or her dependents or an ODSP staff member. Any person may provide information to an ODSP staff member that triggers a request. In certain cases, a family member accompanying an adult through the application process is appointed from the outset.[435]

The process to appoint a person to act for a recipient does not include a capacity determination; it is based on an informal objective assessment of the recipient’s need for assistance in managing his or her income support according to enumerated factors to be taken into consideration. The factors include whether the recipient has asked for assistance, a reliable third party has provided information that the adult requires assistance and/or the adult frequently runs out of money for food or shelter. There is a strong emphasis on making all possible efforts to gain the recipient’s cooperation and agreement before appointing an ODSP trustee.[436]

A review of the legislative history of the ODSPA reveals that the determination of an adult’s capacity was intentionally omitted from this appointment process. While the Bill to enact the ODSPA was open for public comment, a number of community organizations made submissions against the proposed inclusion of a capacity assessment. Then Director of Policy and Research at ARCH Disability Law Centre suggests that “the reason for removing this provision may well have been a realization that ODSP officials should not make what is essentially a legal determination about a person’s capacity”.[437] In contrast, for a trustee to be appointed on behalf of an adult recipient of Ontario Works, evidence of incapacity from a medical practitioner may be adduced to determine whether the recipient needs help in managing his or her income support.[438] The local Ontario Works Administrator will take into consideration the medical practitioner’s assessment as well as other factors when making a decision.[439]

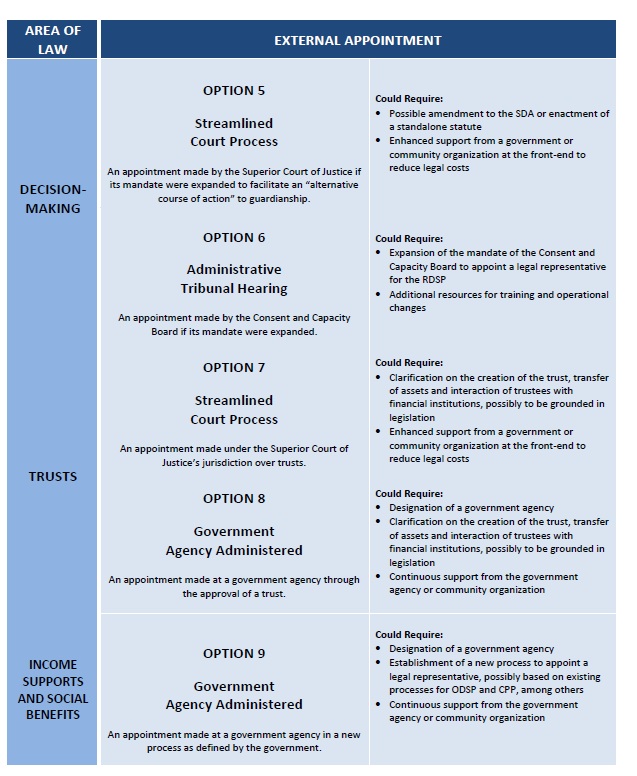

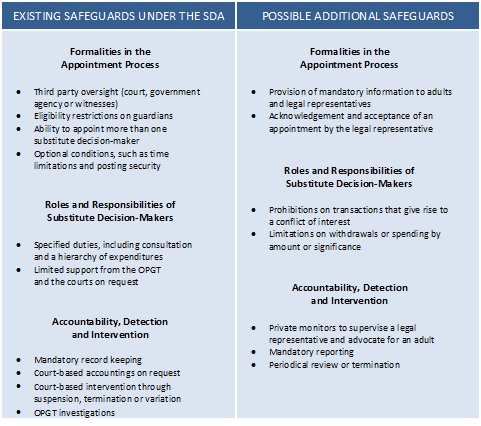

ODSP has several safeguards in place in relation to trusteeships, including mandatory annual reporting, periodic reviews and the replacement of a trustee. ODSP is creating a template for annual reports in order to improve reporting. One of the purposes of these accounting measures is to assist in determining if a recipient still needs assistance in managing his or her income. Concerns have been expressed and complaints made to ODSP regarding trustees mismanaging a recipient’s funds. ODSP investigates these allegations by conducting a review of the appointment, following which it may remove and substitute the trustee.[440] Where warranted, ODSP will make a referral to the OPGT or the police. ODSP can also provide compensation up to a maximum of one month’s benefits in cases of mismanagement if satisfied the recipient would be unable to provide for his or her basic needs and shelter without compensation.[441]

Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security