A. Introduction

The purpose of this project is to recommend a process to establish a legal representative for adults who experience diminished capacity to open an RDSP, decide plan terms and/or manage payments out of the RDSP. Making decisions for an RDSP is very demanding. The RDSP is a financial vehicle that is complex and it requires a plan holder to make educated choices through traditional investment instruments, such as mutual funds. Adults with mental disabilities seeking access to the RDSP may have a need for assistance in RDSP decision-making because their capacity to do so for themselves is diminished. Creating a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries would give them a more accessible alternative to Ontario’s current framework to appoint a guardian, which can involve a complex, lengthy and expensive process. It would also seek to provide them with a less intrusive means to receive assistance by reducing the negative repercussions of guardianship on their well-being.

This section brings together the options for reform identified in each of the preceding chapters. It summarizes these options and discusses how they can be combined as well as implications for implementation.

Findings from the preceding chapters are referred to throughout this chapter and you are invited to consult them for further detail. Of particular importance are the benchmarks that the LCO has articulated based on objectives that the options for reform must meet to be effective (Chapter I.C.2). We propose that a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries would meet the following benchmarks:

- Responds to Individual Needs for RDSP Decision-Making

- Promotes Meaningful Inclusion in the Decision-Making Process

- Ensures that Necessary Protections for RDSP Beneficiaries are in Place

- Achieves Administrative Feasibility, Cost Effectiveness and Ease of Use, and

- Provides Certainty to Legal Representatives and Third Parties.

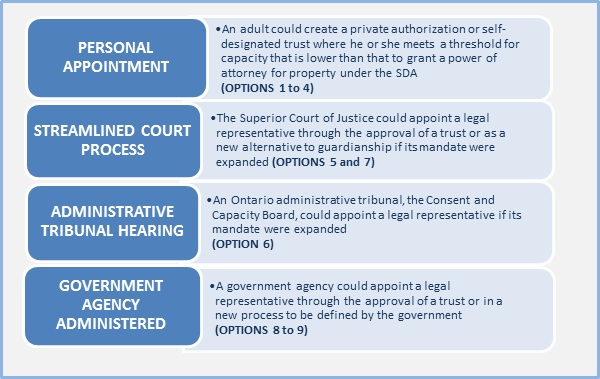

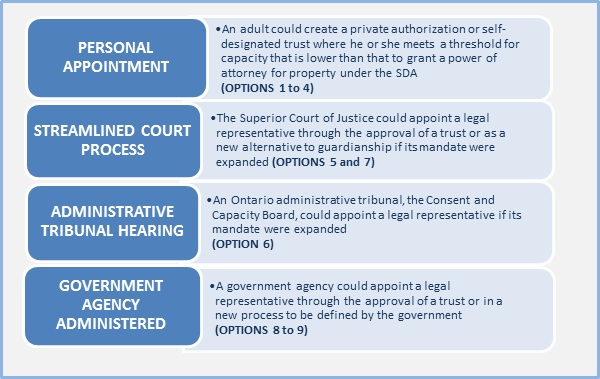

Our summary of the options for reform, immediately below, also refers back to Figure 2, Options for Reform in the Choice of Arrangements. Figure 2 can be used as a visual aid and is located at the end of Chapter V.B on pages 90 to 91.

B. An Alternative Process to Establish a Legal Representative for RDSP Beneficiaries

1. Overview of the Options for Reform and Types of Appointment Processes

Chapter V.B., Choice of Arrangements to Establish a Legal Representative for the RDSP, considered how the general arrangement to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries could be structured. It reviewed existing arrangements in decision-making laws, the law of trusts and the income supports and social benefits sectors. Each of these areas of the law has a process to designate a person or organization to assist adults with diminished capacity in managing their financial affairs. Based on that review, Chapter V.B presented several options that could be adopted in Ontario specifically for RDSP beneficiaries through the following overall appointment processes:

- personal appointments

- streamlined court process

- administrative tribunal hearing

- government agency administered

Personal appointments are widely perceived as preferable to external appointments through a court, administrative tribunal and government or other agency. Personal appointments permit adults who meet a level of capacity to proactively choose whom they would like to assist them and in what way. They are also private arrangements that can be cost-effective for the adult and legal representative, and require less support from government than external appointments.

External appointments generally apply to circumstances where an adult does not have a private arrangement, such as a POA, and the adult’s challenges with decision-making are such that he or she cannot meet the threshold of capacity required for a personal appointment. The RDSP beneficiary could initiate an external appointment process him or herself, or another interested party could do so. A court, administrative tribunal or government agency could then appoint a legal representative for the RDSP based on an assessment of incapacity or on an adult’s demonstrated need for assistance. Responding to an adult’s need for assistance is widely perceived as less intrusive than an assessment for incapacity.

In Ontario, both personal and external appointments exist as options under decision-making laws. Adults can execute a POA or undergo a court-based or statutory capacity assessment if it appears they are in need of a guardian. Offering these two avenues to establish a legal representative for the RDSP should be viewed as a possible combination in the options for reform.

The LCO analyzed personal and external appointment processes that could potentially meet the benchmarks for reform. Many of these included arrangements available in Canadian provinces and territories that the federal government recognized as having instituted streamlined processes or other arrangements that could address the concerns of RDSP beneficiaries in the Economic Action Plan 2012.[667] The arrangements reviewed in this discussion paper consist of special limited powers of attorney, supported and co-decision making arrangements, representation agreements, trusts and representative payees for income supports (often called “informal trustees”).

It is important to know that many of these arrangements could be established through both a personal and an external appointment process.[668] This should be recalled in reading through the options for reform. Co-decision making arrangements and representative payees for income supports are an exception. They are only established through an external appointment, as discussed below.

The LCO has identified options for reform that mirror the existing arrangements, listed above, with some amendments. We do not make any specific recommendations in this discussion paper. Rather, we outline several options for reform with a view to receiving feedback from the public. The options for reform reflect our cursory findings on how a given process would need to be implemented in the Ontario context.

Bearing in mind these general observations, the options for reform are briefly explained in the next section and presented in Figure 4, Options for Reform by the Type of Appointment Process. They are the following:

OPTION 1: A private authorization granted by an adult who meets the common law threshold for capacity.

OPTION 2: A private authorization granted by an adult who meets non-cognitive criteria, such as the communication of desire and preferences.

OPTION 3: A private authorization granted by an adult who meets the common law threshold for capacity and who only needs support to make decisions for him or herself.

OPTION 4: A self-designated trust created by an adult who meets the common law threshold for capacity.

OPTION 5: An appointment made by the Superior Court of Justice if its mandate were expanded to facilitate an “alternative course of action” to guardianship.

OPTION 6: An appointment made by the Consent and Capacity Board if its mandate were expanded.

OPTION 7: An appointment made under the Superior Court of Justice’s jurisdiction over trusts.

OPTION 8: An appointment made at a government agency through the approval of a deed of trust.

OPTION 9: An appointment made at a government agency in a new process as defined by the government.

2. Options for Reform by the Type of Appointment Process

a. Personal Appointments

Example: Joan experiences challenges with her financial affairs and cannot meet the threshold of capacity necessary to execute a POA for property in Ontario. She can communicate a desire to have her trusted friend Paula assist her and make decisions on her behalf with respect to an RDSP. She can also demonstrate her preference to receive the maximum allowable government grants and bonds. Joan could possibly appoint Paula as her legal representative for the RDSP.

The above example illustrates the kind of circumstances that could be appropriate for one of the options for reform based on a personal appointment process (Option 2). Option 2 would permit an adult to appoint a legal representative based on factors such as the expression of desire and preferences, and the existence of a relationship of trust.

There are also other personal appointments in the options for reform. In the LCO’s preliminary consultations, one of the goals for reform that stakeholders identified is the acceptance of a threshold for capacity that is lower than that which is necessary to grant a POA for property in Ontario under the Substitute Decisions Act, 1992. Stakeholders reported that this threshold is unattainable for many adults with mental disabilities seeking access to the RDSP. Therefore, all of the personal appointments considered as options for reform adopt a lower threshold for capacity. These thresholds are defined by either the common law standard or non-cognitive criteria.

Adopting the common law definition of capacity would allow an adult to appoint a legal representative for the RDSP where he or she has the ability to understand the nature and effect of the appointment. A personal appointment using the common law definition could be a decision-making arrangement, such as a POA, as indicated in Option 1. An adult who can meet this threshold for capacity could also create a self-designated trust (Option 4). Trusts are somewhat analogous to a legal representative for property management insofar as the trustee is a fiduciary who makes decision about a person’s property. Several stakeholders in the LCO’s preliminary consultations suggested that a trust could respond appropriately to the challenges of RDSP beneficiaries.

A process based on the common law definition of capacity could also be available to those adults who can make decisions for themselves with assistance (Option 3). Option 3 is modeled on supported decision-making arrangements. Supported decision-making arrangements formalize the role of informal supports that adults with diminished capacity regularly access to assist them. A supporter may be entitled to undertake several activities, including accessing confidential information, giving advice, communicating an adult’s wishes and endeavoring to ensure that his or her decisions are implemented. However, the ultimate seat of decision-making authority remains with the adult, not the supporter. Supported decision-making agreements have not been used or recommended for complex financial transactions. They could cause uncertainty in the context of the RDSP because a supporter’s help would need to be sufficient to enable each adult to enter into a contract with a financial institution him or herself.

In our preliminary consultations, the LCO heard that certain RDSP beneficiaries might not be able to meet the common law threshold for capacity. The common law threshold for capacity to execute an arrangement, such as a POA or a self-designated trust, is low relative to the test for capacity to manage property under the SDA. However, it still requires that the grantor is able to understand and appreciate basic information about the nature and consequences of an attorney or trustee’s powers. Stakeholders reported that this threshold could be unattainable for the adults most directly affected by the LCO’s project because it is acknowledged that they experience difficulties in navigating the complex rules surrounding the RDSP. The common law threshold for capacity could be effectively lowered further if the scope of a legal representative’s powers was restricted to that of a partial plan holder, who does not have authority to decide the timing and amount of one-time withdrawals or the management of funds that have been paid out of the RDSP. This is because those two areas of decision-making for the RDSP (requesting one-time withdrawals and managing funds that have been paid out of the RDSP) contemplate more complex transactions than opening a plan, deciding investments and permitting contributions (see Section C below).

As illustrated in the example above, a lower, non-cognitive definition of capacity could be based on an adult’s ability to communicate a desire to appoint a legal representative as well as factors such as the demonstration of preferences and the existence of a trusting relationship (Option 2). Framing the definition of capacity in this manner reflects a social policy decision to extend personal appointments to adults with significant mental disabilities who may be able to communicate their wishes and values in a way that a trusted person can understand. However, it raises concerns that there could be an increased risk of financial abuse because the definition of capacity is lower and substantively different from traditional cognitive tests under Ontario’s current framework and the common law.

If a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries were created as any of the above personal appointments, it would require the acceptance of a definition of capacity that is less stringent than that required to grant a POA for property under the SDA. This could have great normative value for adults with mental disabilities and those who support them. However, at this stage in the LCO’s project, there does not appear to be sufficient evidence to demonstrate that one threshold for capacity, in particular, would clearly be flexible enough to meet the needs of RDSP beneficiaries in Ontario. There is substantial diversity in the persons seeking to participate in the RDSP, including persons with developmental, psychosocial and cognitive disabilities. Any future recommendations for reform must reflect the lived experience of RDSP beneficiaries to be implementable. Consequently, more information will be required to understand whether a personal appointment process would appropriately address the subject matter of this project in the Ontario context.

b. Streamlined Court Process

Example: Joan experiences challenges with her financial affairs and would like Paula to assist her to participate in the RDSP. Together, they discuss drafting a personal appointment but they do not believe that Joan would be able to meet the threshold for capacity necessary to execute a personal appointment. Joan has a demonstrated need for assistance with RDSP decision-making but does not need a guardian to manage all of her property. Joan and Paula meet with a staff member at a community organization who helps them complete an application to establish a trust for Joan’s RDSP with Paula acting as her trustee. The community organization assists them in filing the application at the Superior Court of Justice for a judge’s approval.

The above example illustrates Option 7, available through a streamlined court process. Under Option 7 a desk application could be used to prepare a deed of trust for a judge’s approval at the Superior Court of Justice. The Superior Court of Justice decides matters respecting the administration of trusts under the common law and statutes, such as the Trustee Act, Rules of Civil Procedure and Variation of Trusts Act.

The Superior Court of Justice also has jurisdiction to decide applications for guardianship under the SDA and, for that purpose, they are required to consider whether an alternative course of action could meet an adult’s needs that does not require a finding of incapacity. Appointing a legal representative for the RDSP could be one such alternative (Option 5). However, little is known about what alternative courses of action are acceptable under the SDA. The statutory procedure that engages the court’s jurisdiction is an application for guardianship and not for alternative relief. Under a strict interpretation of the SDA, the court does not have authority to facilitate alternative courses of action outside of an application for guardianship. As a consequence, a court appointment process under Option 5 would require the expansion of the Superior Court of Justice’s jurisdiction, possibly through an amendment to the SDA or the enactment of a standalone statute. Option 5 could also build on the Court’s experience with applications for summary disposition under the SDA. Summary disposition allows for an application to be decided without a hearing before a judge.

As mentioned above, an external appointment process could include the establishment of different types of legal representatives. Co-decision making is discussed in this section because it is administered through the courts in two Canadian provinces. It occurs only as an external appointment because it is intended for adults with impaired capacity, which could call into question their ability to personally appoint a responsible person.[669] Co-decision making is a less restrictive alternative to guardianship that is available to adults who can make decisions with assistance. It strongly resembles supported decision-making arrangements, discussed above, but differs insofar as a co-decision maker shares legal authority to make choices together with an adult. If a contract were signed at a bank by either the adult or the co-decision maker alone, it may be voidable. This gives co-decision making an added degree of formality for third parties. Nevertheless, like supported decision-making arrangements, co-decision making could cause confusion and uncertainty if used for complex financial transactions because, although decisions must be made jointly, they are deemed to be that of the adult whose capacity is at issue.

For any of the above court-based processes to be cost-effective, speedy and accessible, enhanced support would be required to assist adults and their proposed representatives in preparing an application at the front end. This could reduce legal costs associated with a hearing and limit the court’s role to approving completed documents. A government agency could be charged with administering this support. Empowering community networks to do so could also be a cost-effective and private option, as shown in the example relating to Option 7, above.

c. Administrative Tribunal Hearing

Example: Joan experiences challenges with her financial affairs and would like Paula to assist her to participate in the RDSP. Together, they discuss drafting a personal appointment but they do not believe that Joan would be able to meet the threshold for capacity necessary to execute a personal appointment. Instead, they complete an application to the Consent and Capacity Board to have Paula appointed as Joan’s legal representative. They appear at a hearing before the Consent and Capacity Board in-person.

This example illustrates circumstances in which an administrative tribunal could hear an application to appoint a legal representative for the RDSP (Option 6). As with all other external appointments, different types of legal representatives could be appointed through this process and it could be initiated by the adult or another person.

The CCB is Ontario’s administrative tribunal with expertise in issues of capacity and decision-making. The CCB’s mandate includes creating, amending and terminating substitute decision-making arrangements for incapable adults in the area of health care. This could be extended to the appointment of a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries as a less costly and more accessible alternative to the courts. However, due to the CCB’s resource and operational constraints, this option would be challenging to implement without significant changes to the CCB’s mandate and appropriate resources, which the Ontario government may not have at present.

d. Government Agency Administered

Example: Joan experiences challenges with her financial affairs. Paula would like to establish an RDSP for Joan’s benefit. Paula contacts a staff member at a government agency to tell them of her desire to assist Joan by acting as a legal representative for the RDSP. The staff member meets with Joan and Paula to determine if it would be appropriate to appoint Joan and to help them with the required documentation.

The example above is based on appointment processes that exist in the income supports and social benefits sectors for programs such as the Ontario Disability Support Program, Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security. An adult or another person could similarly apply to a government agency to appoint a legal representative for an RDSP beneficiary (Options 8 and 9).

Government agencies are regularly called upon to appoint a person or organization to manage an adult’s income supports and social benefits. In Ontario, the Ministry of Community and Social Services has expertise in administering these appointments but only for recipients of the ODSP and Ontario Works. Option 8 would enable a staff member to help draft and approve a deed of trust appointing a legal representative for an RDSP beneficiary. In contrast, Option 9 would be based on a process created by the government, specifically to address the issues raised in this project.

Option 9 could be modeled on existing appointment processes in the income supports and social benefits sectors. For instance, an ODSP trustee can be appointed based on an informal assessment of the adult’s need for assistance in managing his or her income support according to enumerated factors to be taken into consideration. The appointment process for the CPP and OAS requires evidence from a licensed medical practitioner that an adult is incapable. Each of these processes stipulates the roles and responsibilities of trustees, requires annual or biannual accounting, and contains other safeguards against abuse and the misuse of a legal representative’s powers. A comparable process could be designed for the RDSP in a manner that is in keeping with the benchmarks for reform.

A government agency administered process would rely entirely on public administration. It would be resource intensive and would necessarily entail the allocation of additional funding, which might not be feasible given the current economic climate in Ontario.

FIGURE 4: OPTIONS FOR REFORM BY THE TYPE OF APPOINTMENT PROCESS

C. Safeguards, Roles and Responsibilities and Eligibility

There are several key issues that merit attention regardless of the choice of arrangement to establish a legal representative, discussed above. These include

- safeguards against abuse and the misuse of a legal representative’s powers (Chapter V.E)

- ensuring an adult’s meaningful inclusion in the activity of decision-making (Chapter V.C.2)

- protections against liability for legal representatives and third parties (Chapter V.C.3)

- the scope of a legal representative’s authority to act as a full or partial plan holder, or to assist a beneficiary in managing funds that have been paid out of the RDSP (Chapter V.C.4); and

- whether community organizations could act as legal representatives (Chapter V.D)

Ontario has existing legislation that provides a good foundation for many of these key issues. For instance, the SDA contains safeguards against financial abuse at the stages of monitoring, detection and intervention. It sets out a substitute decision-maker’s duties to encourage an adult to participate in decision-making activities. Furthermore, the SDA contains provisions to provide certainty to substitute decision-makers for persons who have been found incapable and third parties in the event of disputes. The treatment of the key issues in this discussion paper is intended to determine if different or complementary standards should be developed in the special context of the RDSP.

The reach of a legal representative’s authority is a key issue that impacts the other key issues. Some RDSP beneficiaries may have a need for assistance, not only with opening an RDSP and deciding plan terms, but also with managing RDSP funds once they are paid. Restricting a legal representative’s scope of authority to that of a plan holder would ask that RDSP beneficiaries turn to guardianship when they need assistance with general financial management. However, many have declined to use the guardianship process to establish a legal representative specifically for the RDSP to date.

Extending the scope of authority would make changes to Ontario’s current framework more relevant. Managing RDSP payments could give rise to new opportunities for financial abuse. Because day-to-day expenses are much more personal than investments, it would also make an adult’s engagement in decision-making activities much more essential. As a consequence, added measures to safeguard RDSP beneficiaries against financial abuse and the roles and responsibilities of actors involved with the RDSP would need to be seriously considered.

The two provinces in Canada that have created processes to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries have taken different approaches to this issue. Due to concerns about financial abuse, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice and Attorney General has suggested that a special limited POA for the RDSP could restrict the scope of an attorney’s powers to that of a plan holder who would not have authority to request one-time withdrawals. If an adult requires assistance in requesting withdrawals, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Justice and Attorney General has suggested that full guardianship would be needed because guardianship incorporates additional safeguards against abuse. In contrast, in Newfoundland and Labrador, an adult can authorize designates to act as full plan holders and also receive funds paid out of the RDSP. Safeguards against abuse for RDSP beneficiaries have been integrated directly into the Newfoundland and Labrador legislation, such as the requirement that designates submit annual reports to the Public Trustee.

Depending on how the scope of a legal representative’s authority is defined in Ontario, additional possible safeguards against financial abuse and the misuse of a legal representative’s powers could include innovative measures, such as the use of mandatory forms and information, limitations on withdrawals or spending after a specified amount, and the appointment of a private monitor to advocate on an adult’s behalf. The roles and responsibilities that are currently required under the SDA could also be complemented by a more detailed set of duties for legal representatives to fulfill. These could include requiring legal representatives to consult with adults on transactions that significantly affect them, such as exceptional withdrawals from the RDSP. A legal representative could also be obliged to comply with an adult’s choices, unless it would be unreasonable to do so. Furthermore, explicit reference could be made to third parties’ ability to reasonably rely on a legal representative’s instructions.

D. Important Issues for Implementation

1. Sources of Government Support

The RDSP was established by the federal government and it is administered by federal government agencies in conjunction with financial institutions. Should the Government of Ontario choose to implement a process to establish a legal representative specifically for RDSP beneficiaries, it could lend its support in a number of ways.

The creation of a personal appointment process would likely have to be grounded in legislation, either as a standalone statute or an amendment to the Substitute Decisions Act, 1992. A self-designated trust is a possible exception. If the LCO’s consultation phase shows that RDSP beneficiaries would be capable of creating a self-designated trust, legislative changes might not be necessary because a trust deed can be executed under the common law. However, it is not clear whether a beneficiary would have legal authority to transfer RDSP funds into a trust because the RDSP contains mixed contributions from public and private sources. In order to meet the benchmarks for reform proposed in this discussion paper, a trust should also adhere to minimum criteria relating to key issues, such as safeguards against abuse. Moreover, the interaction of the trustees with financial institutions, which already hold RDSP funds in trust, would need to be clarified.

An external appointment process could be grounded in legislation or, as a creative solution, it could build on the jurisdiction of the Superior Court of Justice, Consent and Capacity Board or government agencies, such as the Ministry of Community and Social Services. The respective mandates of these public bodies were discussed at length in Chapters IV and V.B. It is not certain whether a process to establish a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries could properly fit into their existing mandates, for instance, as a specified area of practice or programming. If it could, the affected public bodies would surely require clear direction from the Government of Ontario on how to incorporate a process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries into their operations.

Any options for reform must be cost-effective and administratively feasible for the Ontario government as well as RDSP beneficiaries, financial institutions and other interested parties. The LCO has noted throughout this discussion paper that community networks could provide a source of enhanced support in preparing applications to appoint a legal representative. Private individuals and not-for-profit organizations could also act as monitors to oversee that an arrangement is implemented effectively. Nevertheless, community networks and private individuals would still benefit from education delivered by the government, as would RDSP beneficiaries and their supporters. The provision of education is reviewed below.

2. Provision of Information to Increase Accessibility

The provision of information to increase the accessibility of an alternative process would be an important area for government support. Chapter V.E on safeguards against abuse discussed the advantages of mandatory information to guarantee equal access to a minimum level of education for those persons most directly affected. Before engaging in the process to establish a legal representative, however, adults and their supporters must first know about the process.

Adults learn about the RDSP at financial institutions and various intermediaries. These entry points were discussed in Chapter II.A.3 and include families and friends, caregivers, legal clinics, private trusts and estates lawyers, ODSP personnel and community organizations. In the LCO’s project on Increasing Access to Family Justice Through Comprehensive Entry Points and Inclusivity, we focus on how entry points to the family law system “can play an important role in informing families about their options, referring them to relevant services and advising them on the best way to address legal challenges and family disputes in ways respectful of their religious, cultural, economic and other characteristics or needs”.[670] Not unlike the family law system, adults seeking a legal representative for the RDSP are most likely to begin their search for information by talking to their informal supporters and service providers.

The LCO believes that the provision of information in appropriate formats, languages and locations will be crucial to the successful uptake of reforms. It is suggested here that information on an alternative process could be disseminated through entry points that are situated within the community networks that adults with mental disabilities commonly access.

3. Coherence with Other Areas of the Law

As a final matter concerning the implementation of reforms, we believe that an alternative process must be consistent with other areas of law that could be impacted. The federal ITA, common law and Ontario’s decision-making laws are all sources of law that presently affect the establishment of a legal representative for the RDSP. Although future reforms may be specific to the RDSP, they could potentially conflict with these laws. Care should be taken in considering which options for reform would least interfere with existing laws and, where possible, measures to promote coherence could be adopted. For instance, an arrangement for the RDSP could be terminated where a guardian is appointed to manage an adult’s financial affairs. Decision-making arrangements created in other jurisdictions, such as POAs, could also be recognized under a conflict of laws provision to enable adults traveling from elsewhere in Canada to access the RDSP in Ontario. The SDA contains a conflict of laws provision that could be used as a model.[671] These and other areas that call for measures to achieve coherence will be considered in light of the LCO’s recommendations in the Final Report.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

44. Are there ways to promote coherence between a process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries and other laws in Ontario?

45. Are there ways to create consistency in a process for the specific purpose of establishing a legal representative for RDSP beneficiaries across Canada?

46. Do the options for reform raise implications for the implementation of effective reforms in the Ontario context that were not identified in this discussion paper?

47. Do you have any other comments on this discussion paper or on the LCO’s project more generally?

| Previous | Next |

| First Page | Last Page |

| Table of Contents | |